By Leah Martindale, Third Year, Film & TV

He is remembered as one of the great filmmakers of the 1940s, but his key biographers believe he was also an early example of a gay or bisexual man working in a less than accepting environment.

Vincente Minnelli is widely known for directing spectacular theatrical and cinematic musicals, comedies, and melodramas, as well as fathering Liza Minnelli with the equally talented Judy Garland, who he met onset for Strike Up The Band (1940) and fell in love with onset for Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). Four times married, with two children, he has a striking and deeply contented second legacy, one debatably as a closeted gay man.

Minnelli is widely recognised in certain circles without debate as a gay man. In others, the assertions are widely disregarded and disputed. In Mark Griffin’s words in A Hundred or More Hidden Things: ‘Despite the fact that Minnelli was married to Judy Garland and three other women…it was generally assumed that he was a closeted gay man who, due to the societal conditioning of his era, felt compelled to marry and procreate.’

So where did this legacy come from to begin with, and how has it survived so tenaciously in the years since his death?

Judy Garland performing "Mack the Black" in THE PIRATE (1948) dir. Vincente Minnelli/chgph. Robert Alton pic.twitter.com/wmYMbRhXi4

— Dancer on Film (@DancerOnFilm) February 28, 2019

One major player in the rumour mill was the aforementioned first wife, Garland. Emerging in other extracts in Griffin’s book are the recounts that Garland was ‘paranoid’ about Minnelli’s bond with Garland’s coworker, the eternally handsome and charming Gene Kelly. With rumours that Kelly had feelings for a male stand-in, this theory seems to have legs of its own.

Whether Kelly and Minnelli had an affair or not, the theories have emerged from multiple sources. Minnelli was wildly flamboyant and adored the stylistic side of dramatics, and his closest confidants purportedly ‘never doubted his true identity’. While his own autobiography, I Remember It Well, manages skillfully to avoid the topic at all, other authors have taken it upon themselves to lift the veil.

Alongside Griffin, legendary film critic Emanuel Levy delved into the director’s complex legacy with the first full length Minnelli biography in 2009. There seems to be a vast quantity of evidence pointing to the fact that Minnelli was openly gay in New York, before a move to Hollywood forced him back into the closet.

Levy characterises Minnelli as having ‘a troubled sexuality’ in an interview with Advocate, as well as stating he believes Minnelli ‘chose to become bisexual’. Despite this interview only being little under a decade old, the latter statement feels centuries more antiquated. As much as we can understand Minnelli did not ‘choose’ to become gay, we must know he did not choose to alter his inherent sexuality to be with the women he was.

Gene Kelly with director Vincente Minnelli on the set of An American in Paris (1951) pic.twitter.com/CUwdrvPN45

— Conrad J. Barrington (@cjubarrington) March 14, 2019

Either Minnelli was bisexual all along, discovered or changed within himself over the course of his life and career, or the saddest option of all: that a director, artist, and human being adored across Hollywood lived the majority of his life hidden.

Minnelli is known to have reinvented himself from humble beginnings, the son of a ‘tent theater’ musical director and touring performer, into a ‘snobbish’ preconceived image of what it was to be an artist. This reinvention, delving into the flamboyancy he is so fondly remembered for, may also have catalysed his reinvention into the image of an acceptable straight man.

History remembers the careers of men whose image has been shaped by their coming out, Freddie Mercury and Elton John to name just two immortalised recently in cinematic biographies. Levy speaks candidly, perhaps harshly, and with an air of authority, of Minnelli and Garland. This authority with which a man unknown to both can speak on a marriage which ended nearly seven decades ago is exemplary of a common theory, shared by myself, on Minnelli’s potential closetedness.

Gigi (1958) / Warner Bros.

Jane Fonda notably told Levy, ‘We could do drugs and have orgies and there was no press.’ However, as Levy goes on to note, a studio Minnelli worked with were upset by his wearing makeup, after which it immediately ceased. As easy as it is to believe that in a pre-internet, and, to an extent, pre-paparazzi world, an openly gay man such as Minnelli may have found it easier to escape scrutiny, this is a fable.

Born ‘Lester Anthony’, Minnelli came from a family of mixed heritage - French-Canadian on his mother’s side and Sicilian revolutionaries on his father’s. Gay rights moved slowly in America, and debatably even slower in central Europe. With the American Psychiatric Association diagnosing homosexuality as ‘a sociopathic personality disturbance’ in 1952, Minnelli not only risked social and familial disrepute, the fall of his career, and divorce as a consequence of coming out - he risked institutionalisation.

Minnelli spent much of his life avoiding sexuality speculations, and yet they have followed him beyond the grave. Much as Marilyn Monroe’s life was spent hounded by her mother’s mental illness and trying to avoid it, Minnelli’s life has been stalked by a spectre. The aforementioned Mercury and John’s legacies are irremovable from their sexuality.

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) / Warner Bros.

As the product of a much older generation, Minnelli’s secrecy at least allowed his legacy to be clouded by doubt, and not the permanent marker of other similar characters. With historians, critics, and amateurs alike able to speculate on breadcrumbs, how much would his legacy be changed by the whole loaf? Minnelli’s secrecy allowed his art to speak mostly for itself, which I’m sure was his intent.

How many more of history’s giants were forced into the shadows by a society too far behind to catch up with them?

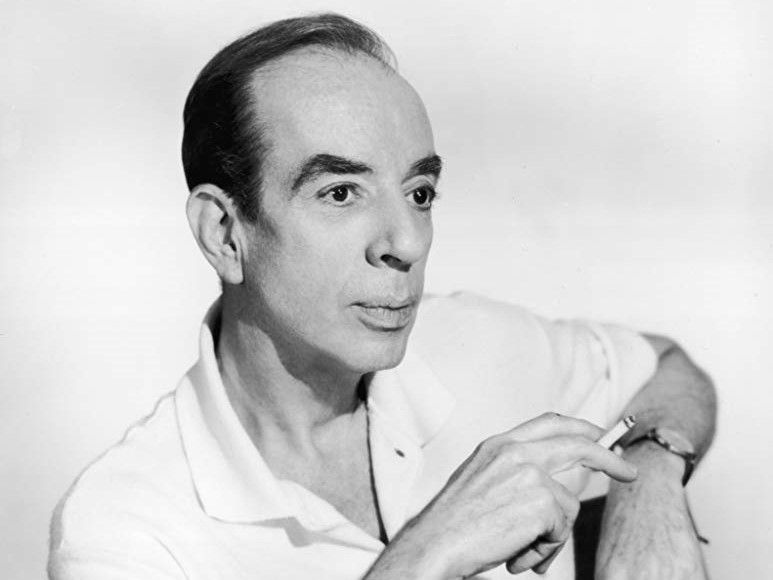

Getty Images / Photo by Hulton Archive

Where does Minnelli rank as an early influencer of Hollywood movies?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter