By Esme Hedley, Second Year, Biology

The first part of Epigram Film & TV’s series on LGBTQ+ representation in media questions the lack of intimacy shown in non-heterosexual, onscreen couples.

To younger audiences, sex scenes in films are unknown and uncomfortable. It makes sense then that in certain films, these scenes are censored for universality. As we grow up, this prudish attitude to sex leaves us and so does this censorship; instead we enjoy seeing characters bond in scenes that often enrich storylines as they bring in real life, complicated, and often messy sex.

But this seems to only really be reserved for straight people, and queer sex is constantly being put back in its box, sanitised for a wider audience or reserved for indie films. Is this fair? Is it more important that in omitting queer sex scenes, these films reach a wider audience to promote acceptance? Or is it doing queer people a disservice, making queer culture more approachable but still keeping it at arm's length?

Watershed / Disobedience

Fran Tirado, Deputy Editor of Out magazine, recently published an essay in which he claimed that ‘to be queer is to be sexually free’, and that to be free is to ‘break away from the chokehold of heterosexual respectability politics... sex, and stigma’. He argues that many films are still trapped in this chokehold, including recent box office hits Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) and Call Me By Your Name (2017).

Though centred around queer characters, the exclusion of sex from films like these is now a joke in the queer community, one where directors ‘forget’ to put them in. Doing this, it can be argued, removes key moments of joy, political identity and accuracy in their portrayals of the queer experience.

This year’s Academy Award winning Bohemian Rhapsody has been widely criticised for its disconcerting attempt to distance Freddie Mercury’s homosexuality from his art, and its framing of his AIDS diagnosis as a punishment for his queerness. The film also shapes Mercury as a one dimensional promiscuous gay man, reducing his seven year monogamous relationship with partner Jon Hutton to a single kiss.

Bohemian Rhapsody won Best Editing for editing out all the gay sex scenes.

— Gonzalo Cordova (@GonzaloRCordova) February 25, 2019

Its exasperating perpetuation of stereotypes only encourages parts of society to continue viewing queer identity and sex in this negative, reductive way. Other representations are contrasting and confusing; from a more everyday perspective, the reality is that in most film and television addressed at teens, queer men seem to be gentle and sexless - note the trope of the gay best friend, ‘who talks about how hot guys are but never touches one’. No wonder that for so long queer people have found refuge in literature which openly and accurately depicts how it feels, physically and emotionally, to be gay.

If sex does find its way into queer films it is often inaccurate or, as is often the case for women, performed and orchestrated for the male gaze. Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013) is an infamous example - Julie Maroh, the author of the novel on which the film is based, took issue with the film’s sex scene, reportedly saying ‘as a lesbian there was something missing from the set: lesbians’. While indicative of a wider issue of diversity in Hollywood, instances such as this again fuel the idea that gay sex is a sort of scandalous unknown.

Most frustratingly, ‘raunchy’ sex scenes between a man and a woman have not prevented big films from receiving nominations for top awards, such as Atonement (2015) and Blue Valentine (2011). In addition to this, less mainstream visibility of gay sex allows porn to be the media representative, reinforcing damaging stereotypes, like the idea that all gay men have perfect bodies. For women, this is even more confusing, as lesbian sex in mainstream porn is designed for male visual pleasure, fuelling its inaccuracy.

had the absolute pleasure of speaking to Desiree Akhavan about THE MISEDUCATION OF CAMERON POST and why the sex in blue is the warmest colour SUCKS, a take i will champion until the end of time. interview for @theskinnymag is in print & online now ✨https://t.co/KpIgO8x438

— katie goh (@johnnys_panic) September 4, 2018

As Tirado neatly summarises: ‘Straight gatekeepers are an unfortunate necessity if you want LGBTQ+ films to be in the mainstream, which means that uncensored queer sex in films remains niche.’ Nobody is saying every queer film must include sex, and it would also be refreshing to watch a film about gay people that does not centre itself around sex.

In addition to this, it is not to say that queer sexuality and eroticism can’t exist in circumstances that forgo explicitness to make a bigger point about ideas of gender and sexuality. Critic Kyle Turner, of Paste Magazine, argues that there is a long list of such films that no one cares to remember or mention. Perhaps the biggest issue here is the lack of access and education of these niche films, which unfortunately only makes mainstream representation more important.

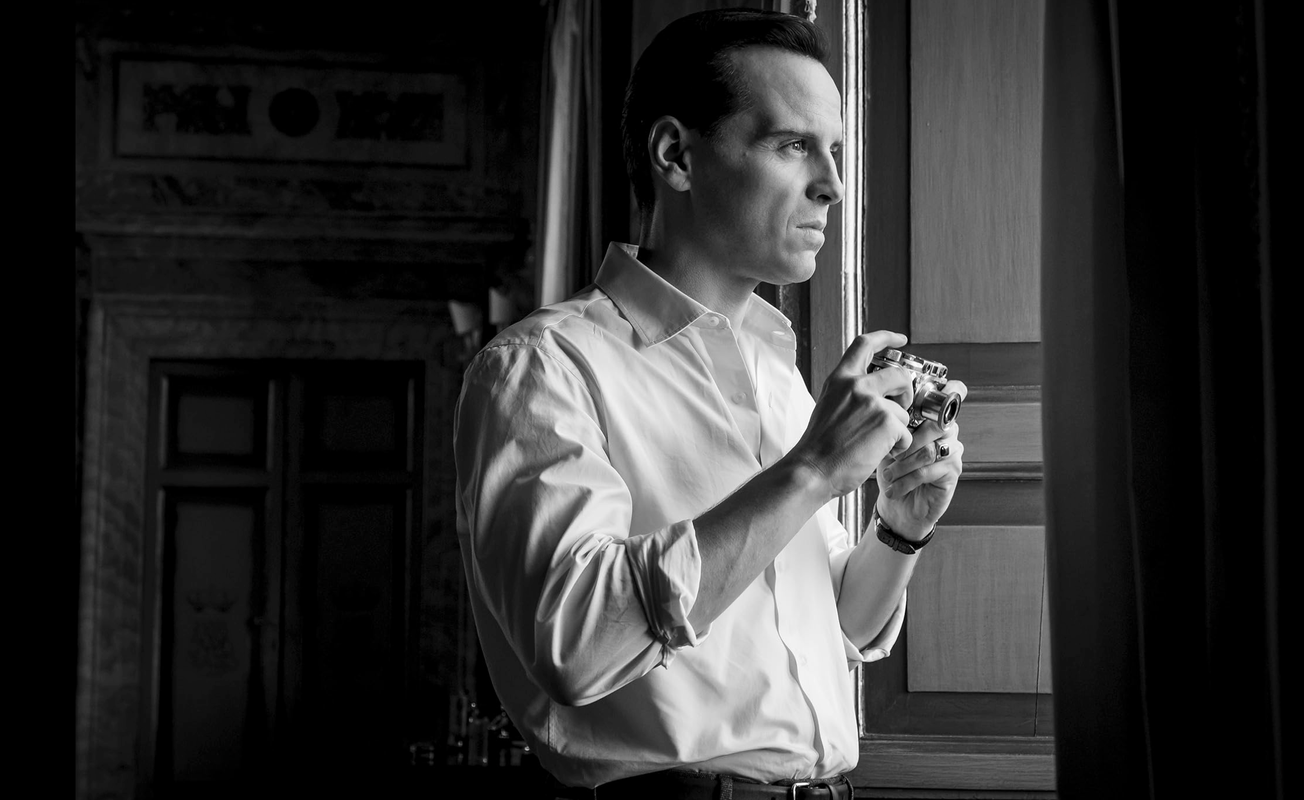

Accessible queer sex scenes are becoming more widespread: recent examples include Moonlight (2017), Disobedience (2017), God’s Own Country (2017) and Tangerine (2015). Those in The Favourite (2018) have been especially praised in the way they do not overpower the movie by reaching too hard for the male gaze, while also being fun and sensual.

almost finished queer as folk (uk) and it's so gorgeously trashy. the women characters are brill and some of the early 2000s looks are 👌🔥 10/10 self insert content pic.twitter.com/yWAIX9V8rq

— rob_n (@dozenrobins) January 1, 2018

Is there a reluctance to show gay sex scenes on screen? Maybe. The frustration lies within the inaccuracy of the sex when it is chosen to be included, or in the reasons behind its omission. Bohemian Rhapsody’s choice to not include queer sex only reinforced the historical inaccuracy of the film, and it was a missed opportunity.

Perhaps what we need to see is more same-sex intimacy, where people are not reduced to just their bodies but instead depict a more accurate, nuanced expression of same sex desire. No one is expecting graphic sex scenes in any mainstream film, but the inclusion of queer sex, however brief, would show society that it is not something to be afraid of seeing on screen.

Featured Image Credit: BFI Institute / God's Own Country

Can you see a clear difference in how straight and gay relationships are shown?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter