By Lily Grace Oliver, Third Year Film and Television

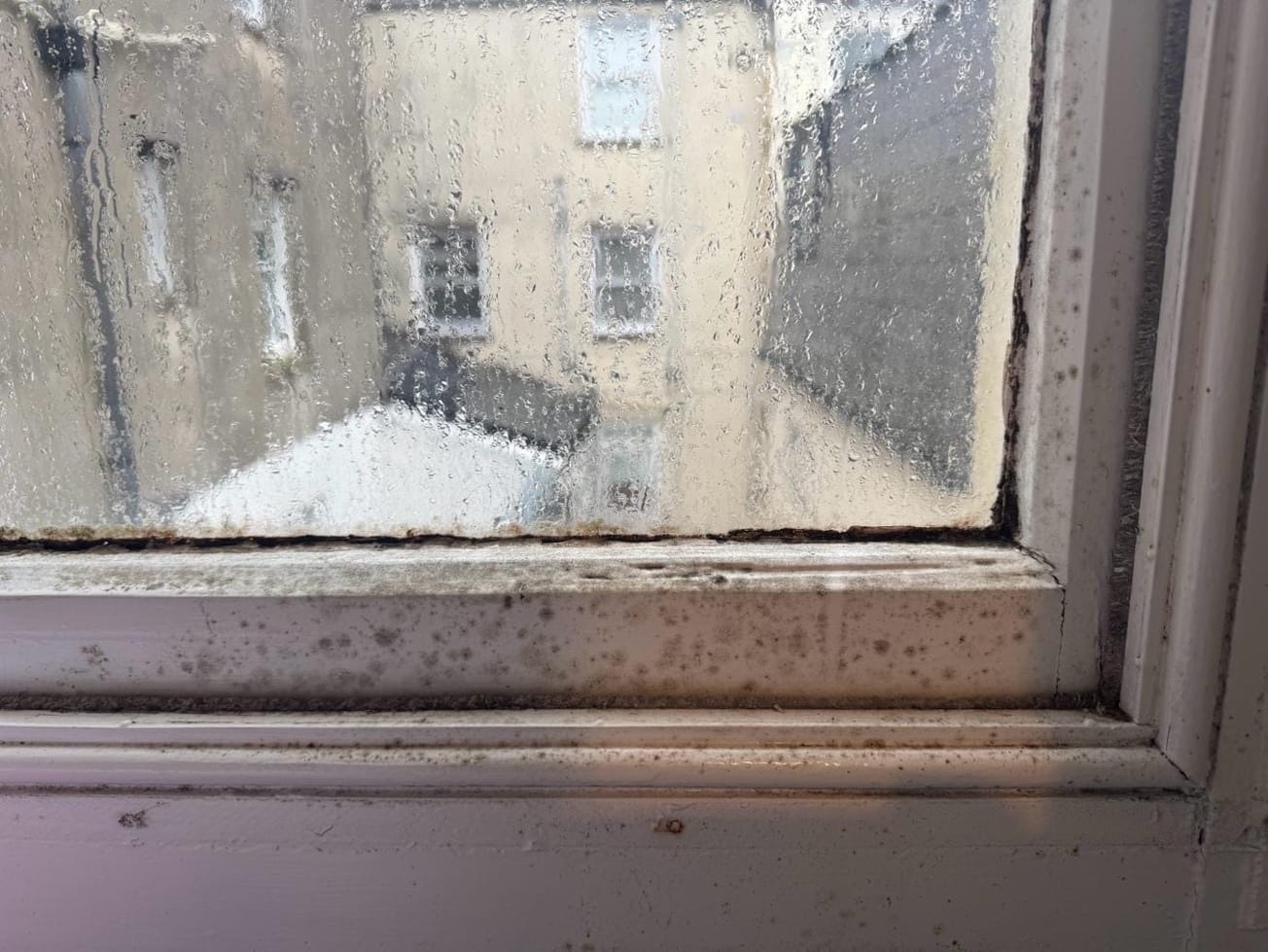

‘Oh, you’re staying at the Ghetto.’

‘I’m staying where?’

‘University Hall. Everyone calls it the Ghetto, you know.’

The boy grins after saying this. I notice people’s eyebrows raise slightly upwards when I state my dad’s job at my school was the janitor. I used to think it was impressive that the most famous person who went to my state school was reality sensation Katie Price, until I began to go to lectures with the kids of celebrities, academics, and politicians. Name-dropping is like saying what you had for breakfast. I am trying to find my people like any other eighteen-year-old. After asking working class and state school-educated students to anonymously speak about their experiences two years later, these high volume responses exposed a long ignored public issue.79% of working class, state educated and lower-income students reported negative experiences within these performing arts societies in my feedback form at The University of Bristol.

I find that whilst some committee members at once express support or at least stay in contact with me about finding ways to combat these issues, others are tellingly silent. There is an element of genuine fear in admitting something is wrong. And who wants to speak out about a system that benefits them? That silence is what pushed me to publish this article.

In 2025, it was reported that over 582,477 students attend private school. This is only a tiny 6.4 per cent of all students in the UK. Despite this, there is a sizable proportion of privileged people within performing arts societies. Within the state-educated students, there is a further gap as well between well-off, or middle-class students and low-income, working-class ones. Class operates as culture – someone's accent, clothes and knowledge of arts dictate how much respect they should be given. Access is often interpreted as merit - it’s a core classist mechanism where wealth masquerades as dedication to the craft. Students who lack financial stability lack the opportunity to have their skills nurtured. There is not only a massive gap in drama training at elite private schools versus often underfunded state school drama departments, but also a more general belief in richer students and their individualised potential to succeed. These are more pay-to-win systems than actual meritocracy. Well, unless you have a family member with a Wikipedia page.

‘I am left without knowledge that is deemed foundational. It is daunting when people do not understand and humiliating when you try to explain,’ one student says of their experience. At one point, my family is so poor that I am withheld from entering a bus for a school theatre trip and have to stand embarrassingly outside the bus as my mum screams at my teacher to let me on. ‘At first, you think all these wonderfully talented people have some innate gift that makes you so much worse than them, until you hear about their years of private training that your parents never could have afforded,’ another student states. Whilst the societies do offer helpful workshops with industry professionals focusing on skills, a couple of hours is far different to years of private lessons or the opportunity to go and be in school-related Edinburgh Fringe shows. Failure in these societies and beyond them is more likely to be internalised rather than be seen as a structural advantage to these lower income students. Any illusion of meritocracy further dissolves once students graduate. ‘Because I wasn’t attempting to pursue my dream career in theatre and follow that same path, I often felt that I was not as ambitious as my peers or driven,’ one former student said. ‘When, in reality, of course, I wanted to pursue it, but I did not have the luxury of time and money. The drama school industry is built for the rich. I barely had time or money to commute to London and further whilst studying.’

Being able to take part in so many extracurricular activities can be a luxury. For social events, it’s like a never-ending boozy party train you must constantly board. It’s obviously not the committee member’s fault for organising these, as it is the norm, but it often adds up to a financial barrier that often goes unrecognised to more privileged students. ‘It’s an expectation that we, as lower-class citizens of the university, should attend socials, club nights, bars, theatre trips, and so many more things that add up to so much money that people don’t even realise it’s becoming a burden.’ Being able to attend these activities, trips, or events is also a huge form of social capital. Who wants to host pres at your house when you live an hour away in the dodgy part of the city? ‘As someone from a working-class background, I don’t have the ability to relate to these individuals and therefore am on the backfoot all the time,’ a student comments. Whilst societies offer subsidised memberships, formal financial support directly from the Bristol SU is often difficult to access. The activity hardship fund offers financial support for students, but can be very competitive to get.

‘I often found myself very jealous of the people who never had to work or worry about money,’ a student recognises. Students spoke about the expectation to drop everything and attend rehearsals, even despite other obligations, trying to avoid the perception of being ‘difficult to work with’ if they missed rehearsals. Some students even describe being told to take days off work for unpaid rehearsals. ‘I apologise if I need to miss a rehearsal to earn an extra 50 quid so I can eat on the weekends.’ Joining committees can be a huge burden in terms of the enormous workload and countless meetings for lower income students. Influence within societies therefore often consolidates around who can afford to work for free, or who is willing to sacrifice more at a higher cost in order to gain respect.

Beyond classism, there is a general sentiment of cliques, nepotism and a lack of opportunity for most people wanting to have a go from all classes. ‘It’s so prevalent when people are sidelined,’ one student says. ‘It feels like the society isn’t actually focused on allowing different people from diverse backgrounds to have the chance to experience performing.’ In 2024 it was revealed by Channel 4 news that working class creatives in film and TV were the lowest in a decade. Unauditioned opportunities are essential in giving everyone the opportunity to perform, which needs to be made more of a priority.

Much of the exclusion within performing arts societies does not appear as formal discrimination, but as informal regulation: who is allowed visibility, who is encouraged to be ambitious, and who is quietly discouraged from taking up space. They are difficult to challenge precisely because they are framed as taste, professionalism, or harmless humour. I am told that I shouldn’t put videos of myself singing online because a certain society ‘didn’t like that’, and it isn't ‘their thing’. I sent out an email asking whether I got a recall audition and later heard the private message being told to a group of people as they discussed and laughed at the possibility of me getting one. My background is assigned as ‘rough’ on more than one occasion to my face.

When I step into audition rooms in my second year, my body starts to shake uncontrollably. In a particularly awful audition someone on the panel laughs at me to my face. My stage fright becomes so consuming that I go to a doctor and get prescribed anti-anxiety medication. I feel like I should just grin and bear it. The truth is that less privileged people aren’t allowed to be mediocre or make mistakes the way privileged people can. It’s easy to be confident if you've been given everything your whole life.

Things could be changing. The wider industry in the UK may take longer, but a smaller change can happen now. Lower-income, state-educated and working-class people in performing arts spaces shouldn’t have to exhaust themselves financially and emotionally just to prove that they belong. These discussions shouldn’t be buried at committee meetings. Even after getting the last laugh and beginning my professional career as an actor, I realise how rare that outcome is for people like me – and how many others may just quietly leave these spaces all together. Speaking about classism in performing art societies is not about assigning individual blame but asking about who is consistently asked to work harder, sacrifice more and stay quiet in return. Believing in yourself and not wanting to quit what you love can feel like an act of rebellion in a place that was never built to celebrate you.

Hattie Millard, the ELA Officer of Dramsoc stated ‘we hope to foster a community that supports a diverse range of backgrounds and financial situations and are dedicated to making efforts towards this’.

Featured image: Epigram / Lily Grace Oliver

Do you feel there is a class divide at the univeristy?