By Evie Gifford, Third Year, English Literature

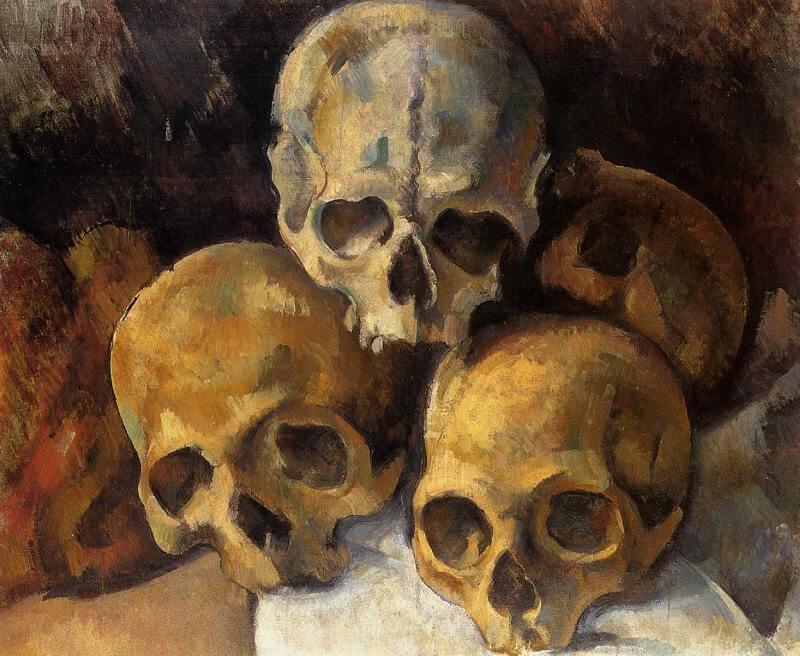

Today, the skull is an immensely popular symbol that influences clothing designs, visual branding, and has come to represent the Rock and Roll genre. The modern relationship with the skull often neutralises the darker and more threatening implications that this symbol may initially confront us with. However, for centuries the skull appeared in art as emblematic of a much more macabre message.

Looking at a human skull can often make people feel unsettled and vulnerable. It is something that belongs to us but is simultaneously unknown to us. We cannot touch it nor see it with the naked eye. It is perhaps this mystery that draws painters to the skull.

Art involving skulls is often termed as belonging to the trope of ‘memento mori’ – named after a Latin phrase meaning ‘remember you must die’. Artwork reminiscent of memento mori endeavours to remind its viewers of impending death and the undeniable nature of their mortality.

One of the most famous paintings to play uniquely with this idea is Hans Holbein’s ‘The Ambassadors’ (1533). The artist distorts the skull, making it unclear what the visual is until viewed from a specific angle that discloses its haunting face. This obscures the memento mori message until it becomes unavoidably and strikingly obvious.

This morbid motif first became popular in the Middle Ages and has maintained its popularity throughout time due to humanity’s perpetual fascination with death and our existence. In the seventeenth century, a common composition for portraiture was to have the subject holding or interacting with a skull. Clearly, there is no more effective way to stimulate discussion of mortality than to confront someone with the literal face of death.

Contemporary artists such as Andy Warhol continue to engage with the subject of the skull. Warhol famously juxtaposes the skull’s dull, achromatic colouring with his characteristic blocking of bright colour. Despite producing multiple studies of skulls, when speaking about death Warhol declared ‘I don’t believe in it’ and said that he cannot comment on it because he has not experienced it yet.

Perhaps we can consider the possibility that Warhol did not intend to attach a memento mori sentiment to these pieces and saw them differently from other artists – experimenting with them for their form, structure, and depth, not their association with death.

Again, moving away from the macabre, the skull is seen to evoke positivity in art when used to commemorate lives, not to warn against the loss of them. This manifests in the artwork of the Day of the Dead, the Mexican celebration famous for its calaveras. Calaveras are visual representations of skulls created not to grieve but to celebrate the lives of lost loved ones.

The political artist José Guadalupe Posada illustrated some of the most recognisable calaveras. His illustration of ‘Catrina’, which is now representative of this festival, is his most famous – decorated gloriously with a hat, feathers, flowers, and a wide smile.

Posada’s skulls are accompanied by his idea that ‘death is democratic’. Despite people’s differences in character, status, and race, underneath, their skulls are all the same. With this logic, skulls have the potential to become symbols of equality. Returning to Warhol’s departure from the tradition of the sinister, his assistant Ronnie Cutrone similarly remarked that to paint a skull ‘is to paint the portrait of everybody in the world’.

In art history, this symbol has adopted different significances and yet has remained timeless. The skull indisputably carries morbidity with it, but some artists have illuminated that not all its connotations are negative. Although skulls will be decorating houses and parties to provoke shock and horror this autumn, it is intriguing to consider what they can signify apart from their spookiness.

Featured Image: Unsplash / Lina White

How do you feel the image of the skull has impacted art?