By Sophia Di Maida, Third Year, English

Over the last few years, social media has seen a steady increase of ‘true crime’ related content. To accompany this rising interest, streaming services and production companies have released more and more shows and films based around famous serial killer cases: from Netflix’s newest series, Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (2022) to Sky's Ted Bundy film, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019).

They’re gory, shocking, and full of gripping scenes. However, the reality is that this content is often poorly dramatized – this isn’t to mean the shows and films themselves are bad, per se, but rather that one has to question whether it is in poor taste to be exploiting very real, very disturbing situations and their victims to turn it into popular entertainment.

This rise in demand for true crime related content for the sake of leisurely viewing might actually be causing more harm than we may first assume. From subsequent desensitisation and romanticisation of criminals, to Hollywood profiting off of real-life trauma, here are some of the issues with taking real-life serial killers and turning them into film and television shows.

The first thing that is potentially problematic is the accuracy, or rather inaccuracy, of some of these docuseries. Netflix’s latest true crime drama, Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, has led viewers to question its integrity in telling the correct story.

Of course, it is hard to take snippets of events that happened and turn it into a full-blown series, especially when no-one knows the intimate details of Dahmer’s (Evan Peters) day-to-day life. However, creator Ryan Murphy seems to have leaned heavily towards hyperbolic dramatization.

For example, Glenda Cleveland (Niecy Nash) is shown as having lived in the apartment next door to Dahmer within the series – we see her being able to hear the power tools he used, and even her being able to smell the decomposing bodies through their shared vent.

This was not the case in real life; Cleveland didn’t even live in the Oxford Apartments building. Cleveland was involved in calling the police for Konerak Sinthasomphone (Kieran Tamondong), but certainly not in the way the series suggests.

Why make things up for the sake of a show? Factual inaccuracy only leads to confusion and an inability to truly empathise with the case as events that truly happened – the Dahmer docuseries certainly doesn’t serve the purpose of educating its viewers at all.

Another issue with these real-life serial killer documentaries is the role they can play in retraumatising the surviving victims or the families of victims. It should not be forgotten that a lot of these crimes were committed within the last century, so in some cases, there are victims that are still alive today.

While there is sometimes consented inclusion of victims, such as Richard Ramirez’s victim Anastasia Hronas, who was interviewed for the Netflix series Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer (2021). However, there are also instances of unconsented representation of victims in these true crime productions. There are many moments in Monster, for example, that are hard enough for the average person to watch – let alone the people who actually experienced it first-hand.

The series doesn’t hold back on the gory details, either, showing scenes such as Dahmer eating human meat at the end of episode six, as well as other seemingly unnecessary and indulgent snippets into the brutality of his crimes. Eric Perry, the cousin of one of Dahmer’s victims, Errol Lindsey, took to Twitter to discuss his rightful distress:

“I know true crime media is huge rn, but if you’re actually curious about the victims (the Isbell’s) are pissed about this show. It’s retraumatizing over and over again, and for what?”

That’s exactly the question – for what? Is it really fair to watch such content for entertainment purposes, knowing that its popularity and attention are only forcing its victims to relive the unspeakable horrors they went through? Especially when the victims weren’t even approached before the filming went ahead?

The casting of ‘Hollywood heartthrob’ actors (Evan Peters, Zac Efron, Ross Lynch – to name but a few) also problematises these docuseries. These casting choices may lead to a romanticisation of the criminals that actually committed these crimes.

Evan Peters is known for taking on difficult characters throughout his acting career, all we need to do is watch one episode of American Horror Story (2011-) to know that, but it’s the public's reactions to these portrayals of serial killers that is becoming more and more concerning.

Tweeting that you find Zac Efron as Ted Bundy ‘strangely hot’ isn’t quirky; it’s woefully ignorant. Yes, you can appreciate the good job an actor did in taking on the role of a cold-blooded killer, but that doesn’t mean you should let yourself forget that the events being portrayed by them actually did happen in real life.

Furthermore, it seems wrong for these actors and directors to be making a profit off these criminals, and their victims, without a percentage going to those who were directly affected by it.

Of course, money is no true compensation for what these people went through, but it’s better to be directed towards those that were affected first-hand rather than the already rich and famous.

All this considered, it isn’t to say that ‘true crime’ content shouldn’t be made at all. Instead, it just needs to be produced with good intentions: to educate its viewing audience, to respect and honour the late victims, and to not romanticise the sadistic serial killer the show or film is based on.

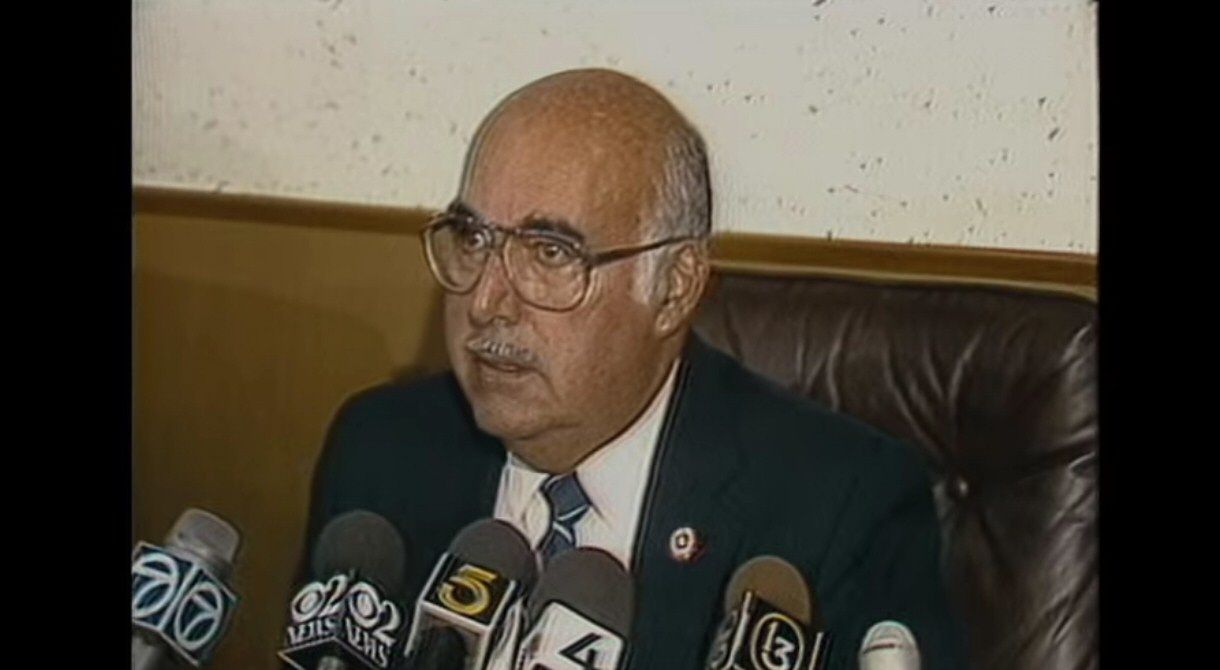

Featured Image: Sundance Institute, Courtesy of IMDB

What is your take on the questionable nature of 'true crime'?