By Leah Roberts, Third Year German

Philosophy can be a heavy subject for the average person to tackle. However, The Good Place is a Netflix comedy series that deals with it in an accessible way.

With new episodes being released every Friday, Season Three of The Good Place, directed by Michael Schur, follows Eleanor (Kristen Bell), Chidi (William Jackson Harper), Tahani (Jameela Jamil) and Jason (Manny Jacinto) as they are sent back to Earth from the afterlife by Michael (Ted Danson) and Janet (D’Arcy Carden) so they can have another shot at getting into the real ‘good place’. Michael and Janet go against the Judge’s (Maya Rudolph) wishes and continue to meddle in the lives of the group to keep the demon, Trevor (Adam Scott), from breaking them apart. The show continues to delve into the topic of ethics and morality, and the struggles the group faces in staying ethical with no end reward.

Youtube / The Good Place

The previous two seasons of The Good Place gives traditional philosophy a modern outlet, with Chidi’s lessons being held in unusual circumstances, and Season Three continues to make ideas of morality and philosophy more accessible to the audience. The comedic tone of the show allows for the discussion of previously exclusive topics in an engaging manner; the show gives you the chance to think about ethics and what being a good person means without feeling ostracised.

Throughout history, traditional religions and philosophies have not been easy to access or understand. Since entering the digital age however, we have been able to access information previously hard to get hold of, making religious and philosophical concepts easier to obtain and read. However, this does not mean that they are suddenly easier to understand; The Good Place allows the audience to digest complex theories and meanings whilst doing the easiest thing imaginable - binging Netflix.

I know I’m a few years late to this party, but whoever cast The Good Place is a *forking* genius. And as an alum of NYU Gallatin (where EVERYTHING was philosophy), this show is painfully brilliant wrapped in comedy gold.

— Phillip Picardi (@pfpicardi) October 12, 2018

Twitter / @pfpicardi

In the Season One, Episode Three, ‘Tahani Al-Jamil’, Eleanor decides to boost morale in the neighbourhood with the ulterior motive of spying on Tahani, after receiving a threatening note that states: ‘You don’t belong here.’ The episode ends with Jason admitting he sent the note and telling Eleanor that he also doesn’t belong in the ‘Good Place’. It largely centres on the idea of karma and how one’s actions have consequences, such as when Eleanor speaks ill of Tahani and the plant she gifted her starts to wilt. The visual comparison allows the audience to understand the confusing idea of karma and the impact of one’s behaviour on scarcely-connected things - in this example, Tahani’s plant.

The beginning of the episode states this explicitly, with Chidi saying in his lessons with Eleanor, ‘Aristotle believes that your character is voluntary, because it’s just the result of your actions, which are under your control,’ meaning that doing good things makes you a good person. With Chidi giving a simple explanation to Eleanor, since she doesn’t seem to grasp the concept, the audience receives the lesson second hand. That Eleanor is such a typical representation of our worst qualities makes her lessons in The Good Place accessible for the average viewer.

Netflix Media Center / The Good Place / NBC Studios

Chidi’s explanation of Aristotle’s philosophy, however, brings us to another main theme of this episode: Aristotle’s theory being invalid since humans can act with ulterior motives. For example, Tahani dedicated her life to helping others, raising, ‘a lot of pennies’ for various charities, but her motivation is the jealousy she has for her sister and her desire to finally step out of her shadow.

On finding out that the ‘Good Place’ is actually the ‘Bad Place’ at the end of the season, the seven deadly sins becomes apparent throughout the series: Tahani acts on account of envy, greed and pride; Eleanor is prone to gluttony and lust; Chidi, even though morally-sound, achieves nothing in his life due to sloth, and even Michael is guilty of wrath.

The episode ‘Tahani Al-Jamil’ introduces the topic by showing the audience how Chidi’s life was plagued with indecision, leaving him with no personality and even hurting the feelings of loved ones and friends, both on Earth and in the ‘Good Place’.

Instagram / @nbcthegoodplace

In a few humorous scenes, Michael tries to help Chidi find a hobby but he fears all of them for different reasons and returns to academia, even though no living person will ever read the work he produces in the afterlife. Since sloth is defined as the failure to act, even though Chidi is not evil, he is still a good person failing to act on his obligations due to his indecision. The humour of Chidi’s failings again allows the audience to absorb the deeper philosophical meanings behind the episode. The whole point of The Good Place is to portray the idea that musing about ethics does not amount to any good in the world- acting on them is what truly makes a difference and brings about a change in a person.

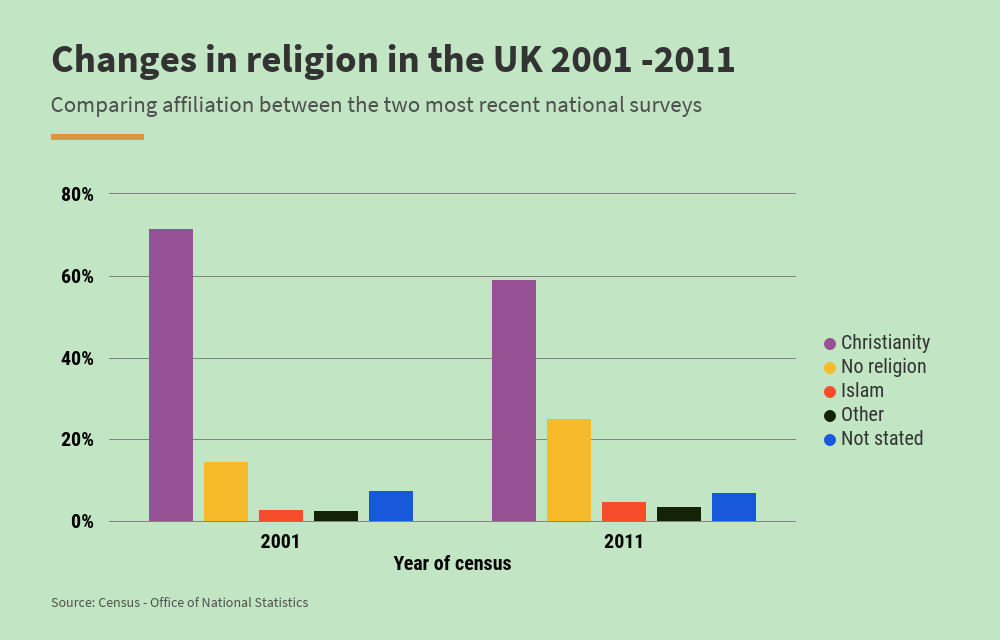

A record number of people in the UK have self-defined as having no religion, 25% in the 2011 national census, with the same decline happening in countries throughout Europe such as Germany, France and the Netherlands. With so many people deciding against conventional religion, it’s no surprise that The Good Place’s creator, Michael Schur, is keen to clear up confusion as to whether his show is a religious one, ‘It is very important to make clear [...] this is not one religion’s concept of the afterlife. [...] The show isn’t taking a side.’

Epigram / Patrick Sullivan

Right from the start of the series, Schur reinforces this idea of inclusivity, with Michael telling Eleanor in the first episode that, ‘every religion guessed about five per cent’ of what happens after death. This inclusivity that Schur continues to strive for in the ongoing season is exactly what makes The Good Place such an accessible resource on learning how to become a better person.

Featured Image: Netflix Media Center / The Good Place / NBC Studios

Has The Good Place helped you understand your Philosophy open units?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter