Epigram is an independent and neutral newspaper, aiming to publish opinions from across the student body. To respond with an opposing opinion, please contact comment@epigram.org.uk or join our writers group

Nina Bryant critises scaremongering health warnings, and questions why visibility isn't also given to debilitating mental illnesses as well as physical ones.

Scaremongering tactics are often employed to deter students from engaging in behaviours that are seen as “risky” – but we often fail to challenge whether these fear-inducing ploys may be affecting the quality of student life.

Scaremongering tactics are no novelty: to this day I am still haunted by memories from school of being told “you should be careful not to accidentally use someone’s razor because you never know who could have HIV” or being told by a sex education teacher that she “wouldn’t let her children sit on toilet seats” when specifically asked if this was a way of contracting STIs.

"Surely there is something unhealthy about scaremongering?"

Of course these experiences were far more traumatic for me than the average person because at the time I was in the midst of developing severe obsessive-compulsive disorder – but let’s just say it wasn’t uncommon for someone to faint during our sex education classes when being shown graphic images of STIs. When discomfort is getting to the level that people are passing out – surely there is something unhealthy about scaremongering?

Possibly the best 40p you can spend. It helps us if you have already tried some simple treatments before you see us #selfcareweek pic.twitter.com/MPuGouzYng

— BristolStudentHealth (@BristolSHS) November 15, 2017

Moreover even if scaremongering tactics do only affect people like me with a disposition towards anxiety disorders - why should my needs as someone with a mental illness be seen as less important than my needs to stay physically healthy?

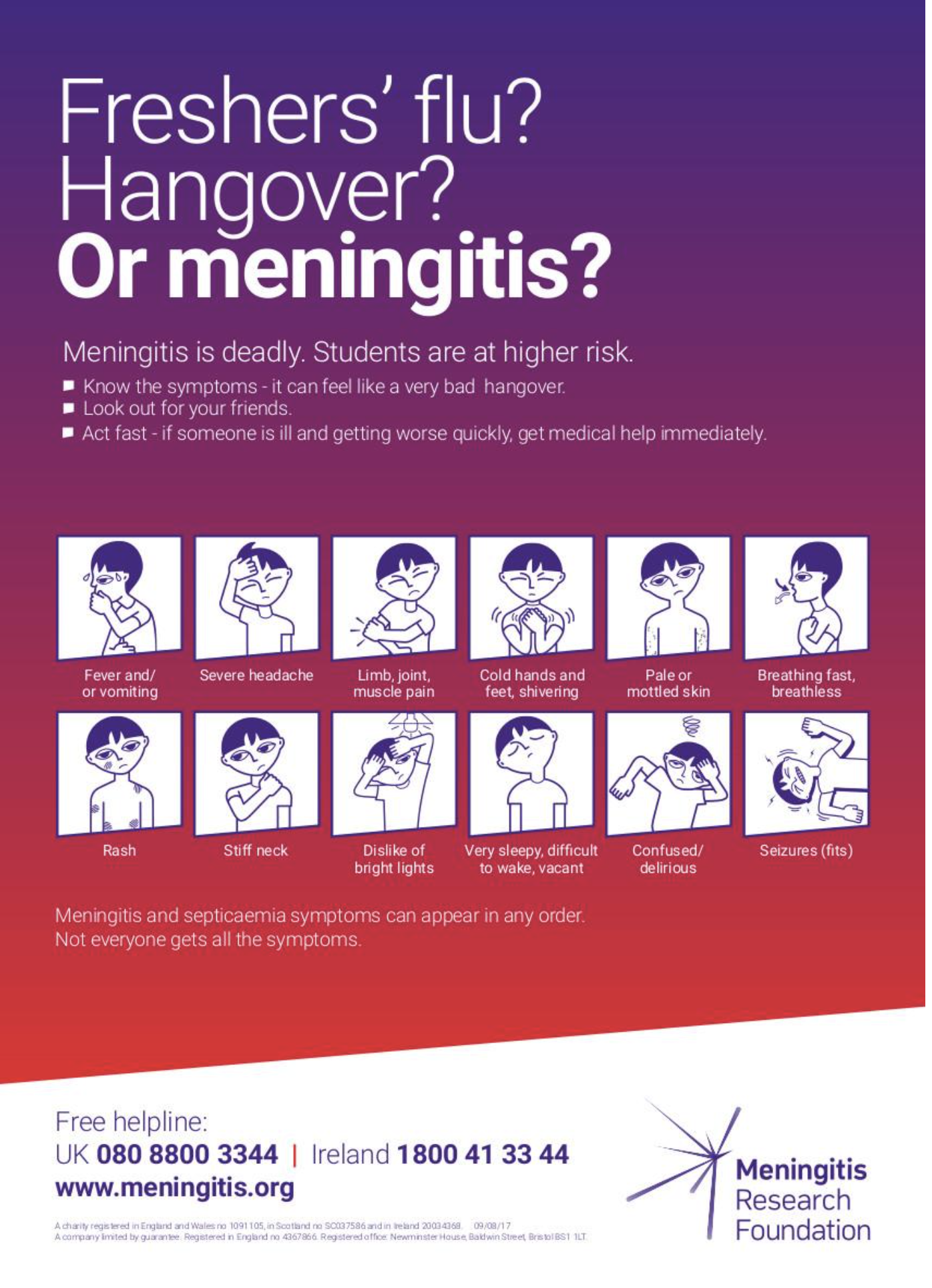

Despite our growing knowledge and independence, scaremongering tactics continue to infiltrate university life without people being aware of how damaging they can be. Sitting in the waiting room at the students’ health service your thoughts may be bombarded with questions like “do I have gonorrhea? Could I get meningitis? Do I have septicaemia?”

"The way that we as a society use emotive language to prevent physical illness is a manifestation of the priority we place on physical over mental health"

You may have never thought it would happen to you but suddenly you are confronted with a poster of a woman who has lost her leg due to bacterial meningitis, telling you that she never thought it would happen to her either.

The way that we as a society use emotive language to prevent physical illness is a manifestation of the priority we place on physical over mental health. For some people brushing off these thoughts may be easy, but for someone with a disposition towards anxiety these images might stick in their brain for years.

Take one example of a slogan from a poster in the students’ health service waiting room which read, “freshers’ flu? Hangover? Or meningitis?”

Image: https://www.meningitis.org/shop/resources/public/a3-student-poster

Not only does this kind of language have the potential to create an unnecessary overflow of demand on the students’ health service, but it also has the potential to create unnecessary anxiety amongst students surrounding what, despite the recent rise in prevalence, is still a very rare disease.

That is not to say that meningitis is not devastating, but arguably insinuating to students that their regular dose of freshers’ flu, or those all too familiar sensations of a bad hangover could actually be signs of a life-threatening illness, is not the way to ensure that they thrive to the best of their abilities at university. Anxiety UK suggests that anxiety affects roughly 1 in 6 young people. I don’t know about you but 1/6 of the people I know have definitely not had meningitis.

"Anxiety can fuel physical problems such as a weakened immune system and eating disorders"

If people are not convinced by the toll that a serious mental illness can take on someone’s welllbeing – they should at least be able to recognize the effect it can have on a person’s physical health. Anxiety can fuel physical problems such as a weakened immune system, eating disorders and unsuccessful suicide attempts leading to long-term health damage. In reality men in their twenties are statistically more likely to die by suicide than any physical illness. So why is it that during freshers’ week we had a talk about recognizing the signs of meningitis but not about recognizing the signs of mental illness?

Unfortunately, raising awareness about increased exposure to physical illness is not the only part of university life that scaremongering wheedles its way into. Discussions about the problems associated with student drug taking often involve using a personal story where drug usage caused tragic physical complications, appealing to people’s emotions without offering large-scale scientific evidence, and often ignoring more prevalent but “minor” issues such as the effects on mental health.

As a result students could either be overly terrified, or ignore the so-called advice promoting abstaining from recreational drug use as the only option altogether. Either way we need to sit back and wonder - what have we achieved by making young people feel scared?

"For students who have worked hard to get into a Russell Group university like Bristol – sometimes we forget that marks and credentials are not the be all and end all"

Even more importantly, when it comes to academia we are often taught to be driven by fear of failure more than we are by the temptation of success. We submit our coursework out of fear of what would happen if we did not – not because we are eager to succeed. Especially for students who have worked hard to get into a Russell Group university like Bristol – sometimes we forget that marks and credentials are not the be all and end all.

For so long it has been ingrained in our psyche that motivation has to come from threat, meaning we can forget that avoidance of risk and failure is not really what student life is about. Being taught that ultimately we have to be in control of our exposure to negative outcomes is going to impair students’ quality of life far more than it will improve it.

When educating young people, the tendency to promote the worst possible scenario needs to be questioned. University life is not about being in control or being perfect, or meticulously avoiding risk, and we need to be communicating that mental wellbeing is as important as physical health and academic achievements.

By Nina Bryant

Featured image: Twitter/@BristolSHS