By Anonymous

Content Warning: Discussion of suicide

The Croft Magazine // Anonymous shares their experience of having a psychotic break whilst at university.

Writing my undergraduate dissertation, working multiple jobs, attending social events, writing for Epigram, going on holiday, volunteering, exercising, cooking: this was my life at the peak of my psychotic break. Outwardly, I was the picture of health and a case study amongst my peers of how to apparently float above stress.

Sleeping once every two nights, crying in my tutors’ offices, creating conspiracies, fantasising about someone living in my head, hearing voices, paranoid about my friends, family, and own brain: this was my life at the peak of my psychotic break. Inwardly, I was a ship bursting at the rafters, floundering, with every crew mate slowly going under.

WebMD defines a ‘Brief Psychotic Episode’ as having symptoms including: hearing voices, seeing things that aren't there, or feeling sensations on your skin even though nothing is touching your body… false beliefs that someone refuses to give up, even in the face of facts. Disorganized thinking; Speech or language that doesn't make sense; Unusual behavior and dress; Problems with memory; Disorientation or confusion; Changes in eating or sleeping habits, energy level, or weight; Not being able to make decisions. Looking back, I had most, if not all, of those symptoms for months.

It amazes me to this day that so much of my illness went undetected. When I had my official break I was admitted to A&E with two flatmates, hearing voices over a Hozier track, awake for 40+ hours and shaking in fear of going back to sleep for who might enter my head when I was gone. What happened after that is beyond me. Not in a pretentious, ‘it was another me, ‘I’ve moved past that sense’. In the fact that I can remember up to mid February, and my memories return in late April/early May.

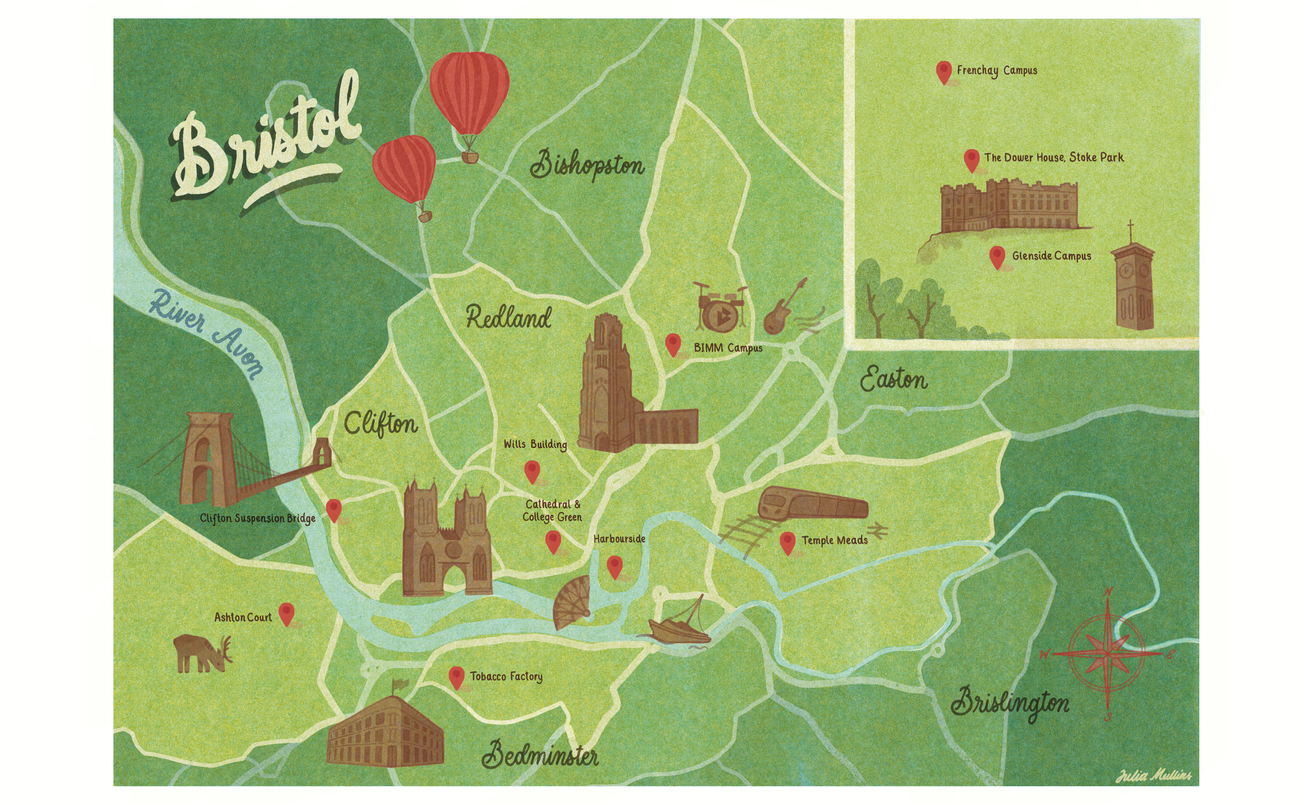

Practically, I know many things happened. I directed a play, I went to Germany, I changed medications, I changed dissertation topics, I shot my graduation film, I saw my friends nearly daily: but when I reach back in my memories for these occasions there isn’t a drunken haze, a half-memory, there is simple blackness. The scariest and simultaneously best part of my break is how ready my own brain was to protect me. The ability of the brain to actively not retain information that is scary or sad is a superpower.

It can be upsetting or even disappointing for friends to learn that apparently pivotal or poignant moments in our lives have been decimated from my mind. It must be offensive that great nights out, deep-meaningful-chats, events and trips were deemed unworthy by my sick mind to retain. This response, however, is indescribably tone-deaf.

I have learned from doctors’ notes, hospital admission statements, my psychiatrist’s notes, and more, the extent to which I was suffering. A lack of trust in the existence and motivations of everything and everyone around me, a daily struggle to maintain the image of myself, a private escalation of logical phobias and illogical ‘super-fears’. If anything, I deserve offence: offence that I told people how I was feeling and they laughed it off. Offence that I told people I hadn’t slept in days and it was chalked up to dissertation stress. Offence that I was isolating myself to unnatural degrees and it was reasoned as hormones.

I am not offended, however. I am not offended because I know in a world of university stresses and deadlines, pressure and expectations, lifestyle and finances, we all feel a little crazy. As someone whose illness was exacerbated by self-imposed and external stresses from every angle, I know as well as anyone how dangerous the university culture of mass-production and high-attainment can be. As much as university broke me, however, it put me back together again.

While it took a long time to feel heard by my doctors, the moment I was, and the severity of my illness was understood, I was fast-tracked to help. Contacted by NHS psychiatrists, seen by a Student Health Wellbeing Triage psychiatric nurse, in regular contact with my angel of a GP, constantly leaning on my wellbeing advisor, senior tutor, and personal tutor: I could not have made it this far without them.

I am in a privileged position in that I am on great terms with my academic and support staff. Years of crying in offices over now seemingly trivial issues have resulted in an understanding from them others can only dream of. I know my illness was, on the whole spectrum of mental breaks, not as bad as it could have been.

That seems ridiculous to say. My final term of my undergraduate was the scariest time of my life. Or it was the best. The strangest thing about recovering from my break has been complete unknowing of how I was. Friends characterised me as erratic, excitable, manic; tutors worried about me, my mother prayed her heart out. I am in the strangely lucky position in that I, the me who exists now, did not have to experience what happened to me.

I am better now. I am better in equal measure due to university support, mental health care, my friends and family, my own graft, and just time. As impossible as it can seem to someone in the position I was in, time truly does heal all. It might hurt, and it might be scary, it might feel impossible that life will ever be anything other than this. It might make you cry, scream, kick; you might go numb. But one day you will wake up humming a tune you heard in your dream, you will see the sun fleck rainbows from a puddle and smile, you will meet a friendly dog on the street and feel warmth somewhere that has been cold and cobwebby since you last checked. Time will have rolled on, and you will have survived. You will have survived, because I did; I survived to tell the tale, and that is it.

Featured: Unsplash / Toimetaja tõlkebüroo

Find The Croft Magazine inside every copy of Epigram Newspaper