By Katie Asha Ramamoorthy, First Year, English

It’s easy to assume that young people today are more politically informed than ever. With constant access to news, debates, and global movements online, political education seems more open and engaging than it’s ever been. However, whilst the internet has democratised access to information, deep inequalities within education and digital literacy mean that not everyone benefits equally.

Instant access: Politics at our fingertips

The internet has revolutionised how young people encounter politics. Government websites, non-profits, and educational institutions now offer free tools ranging from online courses to legislative trackers. News breaks on TikTok before it even reaches television.

Social media has also transformed how young people engage with politics. For many of us, platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter) are the main way we learn about politics. Short explainers, visually-based infographics, campaign videos, and interactive polls make politics feel more engaging and participatory than the formal lessons we may (or may not) have had in school. 'TikTok has boomed since the last election (...) 1 in 10 teenagers say it is their most important news source,' reports Marianna Spring for the BBC.

Movements like Black Lives Matter and Free Palestine have shown how digital platforms can mobilise people globally. Online activism allows anyone to participate — whether that means signing petitions, sharing information, or joining protests. Politics has, in many ways, moved from Parliament to our phones.

However, according to a 2024 study by the Electoral Commission, 72 per cent of young people aged 11–25 want to learn more about elections and politics in school. This statistic shows that while younger generations may be increasingly interested in politics, they still feel that political education at school isn’t meeting their needs.

Misinformation and an increasingly polarised digital landscape

An unfortunate reality is that access to quality political education across the UK remains uneven. Schools in wealthier areas are more likely to offer politics as a subject, while students from less advantaged backgrounds often miss out entirely. University-educated parents are also far more likely to discuss current affairs at home – giving their children a head start before they even reach the voting booth.

'In a digital landscape of AI and news with the aim of engagement over education, separating fact from fiction is harder than ever.'

Teachers across UK schools have commented on the gap in the curriculum: in a 2024 study by the Electoral Commission, 60 per cent of teachers said they felt a responsibility to teach young people political literacy - but 79 per cent do not think their training or professional development in this area is sufficient. Internationally, academic freedom is also under threat: ostensible democracies such as the USA are experiencing a decline in academic freedom, with the study of certain topics restricted. This means much of the responsibility for garnering and navigating political information can fall onto students themselves.

Young people trying to navigate politics for the first time through predominantly online resources can lead to issues of digital literacy. Social media's speed and lack of regulation make it easy for false information to spread rapidly and widely. This can distort public perception, mislead voters, and create confusion around complex political issues. Echo chambers trap users in repetitive content that reinforces their views. Nuanced political issues are often concentrated into a five-second video designed to increase shares and user engagement, rather than provide political context. In a digital landscape of AI and news with the aim of engagement over education, separating fact from fiction is harder than ever.

A snapshot from campus: Bristol students' political engagement

To understand how this plays out in real time, Epigram conducted a survey among a pool of University of Bristol students, asking whether they had voted in the most recent general election — and if so, where they got most of the information that shaped their decision.

A substantial 89% of respondents reported voting in the recent general election, reflecting a high level of political engagement among University of Bristol students. This contrasts starkly with young people’s national engagement: fewer than half of 18 to 24 year olds chose to vote in the 2024 election. One potential factor behind this gap is the link between higher education and increased political participation. University students often have greater access to information, higher political literacy, and a stronger sense of confidence in navigating the political system, making them less likely to feel alienated or intimidated by the voting process. Other factors — such as the political climate on campus, peer influence, or the demographic makeup of the student body — may also play a role in shaping these higher turnout levels.

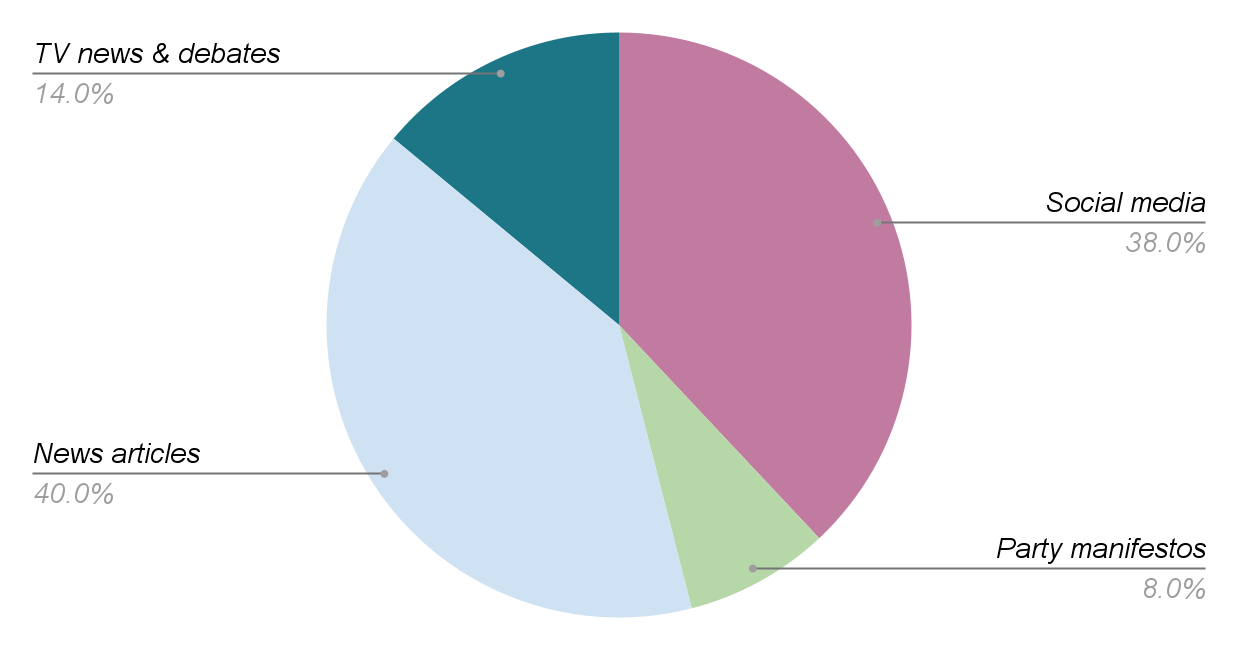

When asked about where they got the information that lead to their decision, responses were split between digital and traditional media:

- 40 per cent turned to news articles, making this the most common source overall

- 38 per cent said they relied mainly on social media

- 14 per cent cited televised news and debates

- 8 per cent used party manifestos

The two most prominent sources of political information for students were news articles and social media, with party manifestos being the least cited, at just eight per cent. This indicates a clear preference for secondary media – such as journalism and digital platforms – over direct party communications like manifestos or debates. In an era where political disillusionment among young people is continually increasing, it is unsurprising that students turn to sources they perceive as more trustworthy than the words of politicians. While the reliability of political journalism has faced increasing scrutiny, major news outlets, particularly in the lead-up to general elections, are still largely viewed as credible and relatively non-partisan (e.g. the BBC). The same level of trustworthiness, however, cannot be attributed to social media, despite its equal prominence as a source of information.

So, the accessibility of political education presents a contradictory picture. Digital tools have democratized access to information and participation, but have simultaneously introduced new challenges related to misinformation and bias. Academic institutions are plagued by deep-seated socioeconomic inequalities that create uneven access to formal political education. Therefore, while information on politics is potentially more accessible to a wider range of people, the quality and integrity of that education is more contested than ever before.

Featured Image: Unsplash / Dmitrii Vaccinium

Do you think young people are more politically educated today?