By Beth Gillard, Third Year English Literature

Pero’s Bridge, named after the enslaved eighteenth-century man Pero Jones, is one of the few memorials in the City of Bristol that bears witness to Bristol’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. Is it good memorialisation?

The appellation of the bridge sparked controversy at its time of opening with views expressed that the name was tokenistic rather than a true acknowledgement of Bristol’s past.

In view of recent events with the dramatic toppling of the statue of infamous slave trader Edward Colston, it remains to be seen whether creating memorials to the slave trade or knocking controversial memorials down is performative activism or whether it provides us with a method of tackling grass roots racism in Bristol and further afield.

Pero Jones was 12 years old when he was purchased from Mountravers plantation in the Caribbean by John Pinney; a merchant from Bristol who enslaved between 236 and 276 people at various plantations which produced sugar and rum to be shipped to Bristol and London. He also set up a company which produced a pro-slavery pamphlet.

Pinney brought Pero to Bristol in 1784 where he served as his personal servant and trained as a barber. Pero fell ill in 1798 so Pinney sent him to Ashton, just outside Bristol, believing some cleaner air may do him some good.

Pero died at around 45 years of age having served Pinney for 32 of these. It appears that Pero was never able to live as a free man again before he died.

Pero’s Bridge crosses the harbour, standing adjacent to the Arnolfini. It was designed by the abstract sculptor Eilis O’Connell and was formerly opened in 1999. The naming of the bridge was first suggested by Paul Smith, a Labour cabinet member who was serving as Bristol’s Chair of Leisure at the time.

This is Pero’s Bridge, opened in 1999. In 1765 Pero Jones was bought by wealthy enslaver John Pinney and was a personal slave for 32 years. The bridge was named to remember Bristol’s links to the slave trade.

— UWE Bristol Library (@UWELibrary) October 26, 2020

To find out more, click here. https://t.co/mLf2obfVXw pic.twitter.com/k975mwdW5U

He intended the bridge to serve as a memorial to slavery however this naming was criticised by Liberal Democrat councillor Stephen Williams who condemned this afterthought as ‘gesture politics’. Instead, Williams believed that a new statue should be commissioned, dedicated to acknowledging Bristol’s role in the slave trade. He also pointed out that Pero was not a widely known figure meaning that the bridge was unlikely to achieve the desired effect.

O’Connell commented that ‘the council can call it what they want, but Pero’s bridge sounds a bit political’. Considering that a memorial to the slave trade had not been the original intention when designing the bridge, it is possible to see why this politicisation can be construed as insincere in nature.

Some felt that the name was tokenistic rather than a true acknowledgement of Bristol’s past.

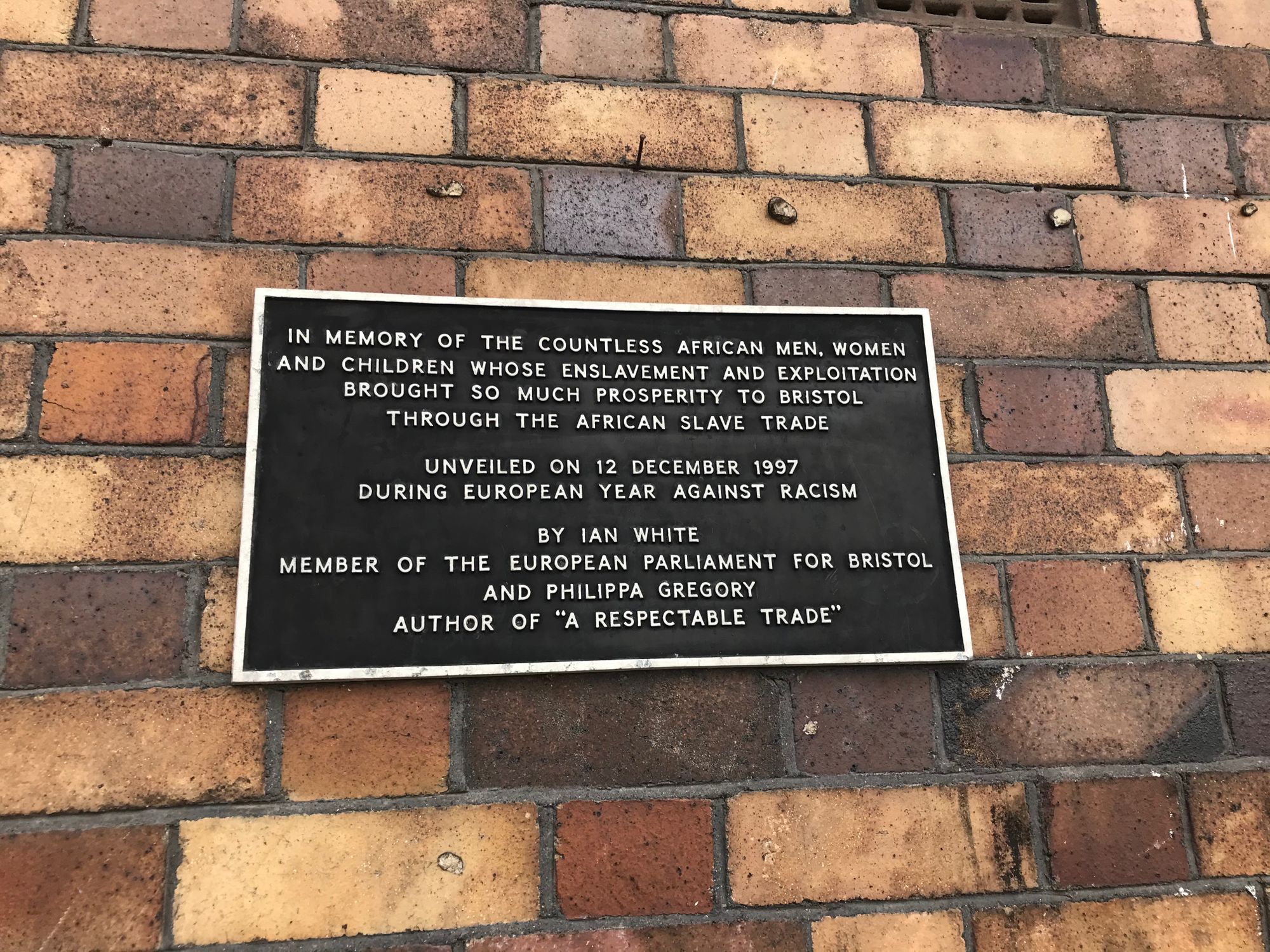

As the only memorial to the slave trade in Bristol apart from a plaque on the side of M Shed, Pero’s Bridge remains largely anonymous to the general population. On a recent visit to the harbourside it is evident that there is no sign on the bridge referencing its significance and no indication of its purpose. Its name seems to be reserved to a few web results and a destination on phone maps.

The question that remains to be asked is how can we memorialise the Transatlantic slave trade appropriately or can we at all? While memorials serve the purpose of acknowledging the harm that was caused in the past, they are a somewhat passive way of instigating change.

In a recent blog post titled ‘Statues, plaques and painful history’, Williams discusses the calls for statues of controversial figures to be removed. He agrees that the toppling of the Colston statue was an ‘appropriate action’ but comments that ‘in most circumstances I believe the balance tips in favour of keeping the statue or place name but with an accompanying plaque or information panel telling the full warts and all story of the person who is commemorated’.

This suggests that for controversial memorials and memorials that commemorate past atrocities alike, there needs to be an element of education to make them meaningful. Memorials such as Pero’s Bridge provide us with a first step to acknowledging Bristol’s shameful involvement in the slave trade.

However, when thinking about the future, it is important that we accompany remembrance with listening to African-Caribbean communities in the city, hearing their stories, how they best think we can acknowledge often hidden histories and celebrate their ongoing contribution to what makes Bristol today an exciting, forward looking and confident city.

Featured Image: Flickr / lovestuck