By Nel Roden, Second Year English

In recent years, women have made up the majority of university students. While this marks a significant step in the right direction for inclusivity in higher education, has it changed women’s experiences with sexism at university? Epigram spoke to female students about their experiences with sexism in University teaching spaces.

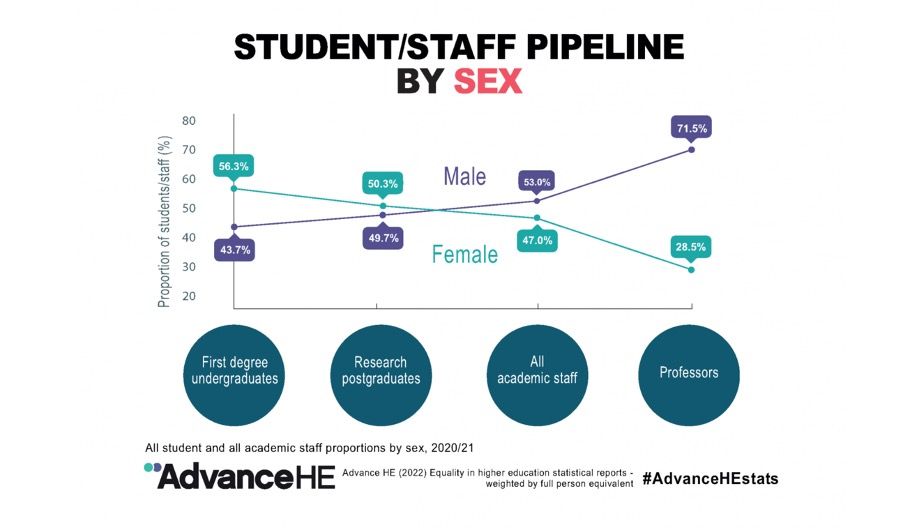

In 2020, the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) reported that female students now make up 56.6 per cent of the UK undergraduate cohort, with their male counterparts amounting to 44.1 per cent. We might therefore assume that proportionate representation persists in higher education teaching fields, however, this is not the case.

Advance HE found that, despite there being more female than male postgraduates, women made up only 47 percent of academic staff and 28.5 per cent of professors in 2022.

These statistics demonstrate the stark reality for women in higher education: although they are proportionally represented at lower levels, they quickly become the minority when progressing further in their careers. As Professor Selina Todd writes, this reinforces ‘the masculine nature of the environment within which they work and study’.

However, it might be assumed that sexism is less prevalent at undergraduate level, where female students represent the majority. To gain insight into sexism in classroom spaces, Epigram spoke to a second year Sociology student.

When asked about her encounters with sexism in seminars, the student stated: ‘Despite Sociology being a female-dominated subject, I have noticed some instances of conversational domination from the few men on my course.

‘In seminars concerning gender, I find that the men present have been relatively respectful, though in conversations on class divisions and other male-dominant theories, I can think of some examples where a male peer has been condescending or dismissive towards myself and other female students.’

When asked about where she thinks sexism in the subject area stems from, she believed that it ultimately boils down to some men ‘undervaluing the opinions of women and feeling a sense of competitiveness due to being on a predominantly female course,’ suggesting that a representative course does not necessarily make it an indiscriminate one.

Women make up about 25% of professional philosophers in the US, the UK, Canada and Australia, which is less than the 51% of women in the general population. Among students, women make up about 30% which is less than their representation among students in general (Goguen)

— Demographics in Philosophy Project (@PhilosophyData) February 11, 2022

The male to female disparity in university teaching spheres is one of many fields that sees a decline in women’s representation in higher level positions. This pattern is especially prominent in Philosophy, one of the most male-dominated professions in the humanities, with men accounting for 71.2 per cent of the profession.

A final-year English and Philosophy student told Epigram, ‘Even in seminars where there are quantitatively equal numbers of men and women, women’s voices are frequently drowned out or made to feel inferior, so the majority of the time it seems as if men dominate the subject. Having spoken to friends who take other subjects in the Arts and Humanities, it seems as if this gender inequality issue is especially bad in Philosophy.’

‘Many of the academics in the department are undoubtedly aware of it. I’ve had numerous lecturers ask specifically for more women to vocally contribute in seminars and lectures. When I represented the subject on an open day it was even suggested that we should be prepared for questions by prospective students regarding the lack of female academics in the department.’

The gender disparity in higher level positions is likewise exhibited in the legal sector, where women make up 61 per cent of solicitors, but only 35 per cent progress to become law firm partners.

Epigram spoke to a second year Law student, who said that she hadn’t witnessed overt instances of sexism on her course. However, she had noticed that ‘almost all male law students possess a certain arrogance I had not encountered before university’. When asked why she thought this was the case, she stated, ‘it is undoubtedly linked to the fact that they are more likely to pursue the more “prestigious” and financially-rewarding areas of law.’

Looking at the HESA stats and in UK white women professors are the fastest growing group of professors currently, even outpacing white men professors last year with a jump of 345 new promotions vs 90 for white men.

— Dr. Ruby (@PaperWhispers) February 27, 2023

Sneak peak of my current work - https://t.co/uHe4oxguVl pic.twitter.com/8xzgPWaLLP

She concluded our conversation by quoting Baroness Helena Kennedy’s book, Eve Wad Framed (1993): “Men head for the high-rewarding areas of practice, but women find their place doing poor folks’ law.”

In both Sociology and Law, female students shared similar experiences of subtle sexism in the classroom, and an undoubtable recognition that, though they make up the majority of the cohort, their career progression is statistically limited.

In STEM subjects, this phenomenon is referred to as the ‘Leaky Pipeline’, defined as: ‘[T]he progressive reduction in women’s participation at the different stages of the career progression in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields'.

The lack of representation of women in STEM fields might contribute to this phenomenon, discouraging female undergraduates to pursue higher positions. Here at the University of Bristol, only six per cent of engineering professors and seven per cent of science professors are female.

‘The digital stench of misogyny is strong’: Uncovering casual sexism in the University of Bristol student community

Girls just wanna have fun... but can they afford it?

Speaking to Epigram, a second year Economics and Modern Languages student agreed that, though she hadn’t experienced explicit sexism, there is still a noticeable ‘divide’ in lectures and seminars. Despite representing the minority as a woman studying Economics, she noted, ‘in a weird way, there being fewer girls than boys motivates me to succeed.’

Women’s representation at undergraduate level has not eradicated the issue of sexism within the classroom—though subtle, it is still present. The poor representation of women in higher academic positions suggests that sexism remains a structural issue in the sector. If this is the case, it is unlikely that sexism in the classroom will be eliminated unless the wider issue of gender representation in academic fields is addressed.

Featured Image: Epigram / Lucy O'Neill

Have you witnessed or experienced sexism in University teaching spaces?