By Olivia Howard, Third year, Geography.

Students today often find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place. Do I choose to focus on my studies for a great degree classification, or gain the work experience which everyone seems to be competing for? It’s the impossible toss-up we’re all grappling with in today’s job climate. Students are asking themselves, can I balance both, or does a degree alone secure me a career once I’ve graduated?

Completing internships whilst studying for a degree seems to be the new ingredient for success. Students envy the competitive edge it gives their peers when breaking into the job market, with the shiny credentials of practical experience - a reassuring endorsement from an employer, affirming their potential. Bristol University provides opportunities to gain such work experience through the SME scheme, many students becoming interns alongside their studies, in both paid and unpaid roles.

And yet, a paper published in 2019 revealed that the average work experience effect on the post-internship job market is zero. Interestingly, what it did find was that those who have some sort of work experience, paid or unpaid, are more likely to have a degree in one of the two top classes, this potentially speaking to the nature of dedicated, conscientious students.

Work experience is still a great thing to gain if you’re unsure about what you want to pursue as a career. Getting experience in different fields can allow students to imagine themselves in different workplaces, and understand whether they align with them or not. Thus, an increased availability of varied work experience across the UK would benefit students nationally.

Realistically, though - for many students, something has to give. Internships, particularly unpaid ones, require significant time commitments that often come at the expense of academic performance. Then comes the impossible question – what’s more valuable to me, a degree costing over £30,000 in loans, or extra, low-paid (often stressful) labour? And what’s the point of all my debt, if I can’t do anything with my qualification anyway?

Nowadays, students don’t have the luxury of choice. The question isn’t should I do an internship in the first place, it’s how do I get one at all. Personal networks and connections, LinkedIn visibility, and the prestige of a university all converge to allow a student to secure an internship. Professionals have commented that these assets are often invaluable in a concentrated, highly-talented and heavily-educated graduating population.

Thus, the question of privilege arises. Those who ‘know people’ can partake in voluntary internships, for which there is no legitimate application process, and so aren’t as competitive. For those who can afford unpaid work through relying on someone else’s income, the benefits are undeniable; they can gain industry exposure, develop connections, and strengthen their CVs.

Similarly, the work experience market disadvantages those who live rurally. Most students can’t up and move cities. They might have a university house, but the opportunities in the area depend on the size of the town/city. If it’s small, with very few companies, the ability to gain work experience is next to none without nepotistic advantages. This creates a cycle of privilege, where only those with the means to support themselves can afford to gain the necessary experience, leaving behind equally capable but financially constrained peers.

What’s missing within this conversation is the value of part-time jobs, and lack of recognition they receive from employers and society. Students working customer service roles, retail work and hospitality positions are incredibly disciplined, balancing timetables and social lives to maintain their commitments. Similarly, such positions teach all sorts of transferable skills such as communication, teamwork, time management, money management and leadership - experience just as vital in the workplace as formal internships. The corporate world needs to recognise and respect these jobs, rather than disproportionately favouring work experience, which is often inaccessible to many students.

And what about the toll it takes on students? The pressure to secure work experience while maintaining high grades is enormous, leading to chronic stress, anxiety, and burnout to be experienced by 68% of the student population.

Unlike the short-term stress of exams, the hunt for internships is ongoing, creating a relentless psychological burden. Research shows that 44% of students have experienced anxiety and depression in relation to finding work experience or an internship. Chronic stress has tangible neurological effects, impairing memory and reducing concentration, and diminishing academic performance. In attempting to prepare students for the working world, are we instead exhausting them before their careers even begin? Or do we all need to buckle up and realise that life is hard, and that includes work?

So, does one have to be prioritized over the other?

Ideally, no—but in reality, yes.

The number of hours required for work experience, and the organisation and time it requires to obtain it, detract from students studying. Furthermore, many students have to negotiate work experience or internship contracts alongside their part-time jobs already - causing even greater strain.

Universities and employers should acknowledge the stress caused by scarce work experience for students - and implement changes to make the system fairer. Whether this is integrating more work placements into degree programmes, giving apt credibility to part time jobs, or understanding and valuing extra-curricular societies at university as work experience in themselves - any way students gain experience whilst maintaining their studies should be credited.

The graduate job market is undeniably competitive, and where we’re going wrong is seeing work experience as something which is all or nothing. It can take many form, and if employers are presenting experience as a prerequisite for graduate jobs, then they should offer enough positions within different sections of their company to provide for the growing graduate population.

So, if you, like me, are feeling stressed by graduation drawing ever closer, and the pressing need to secure a job weighing down on you - take solace in the fact you’re not alone! Quite literally millions of students are experiencing the same thing.

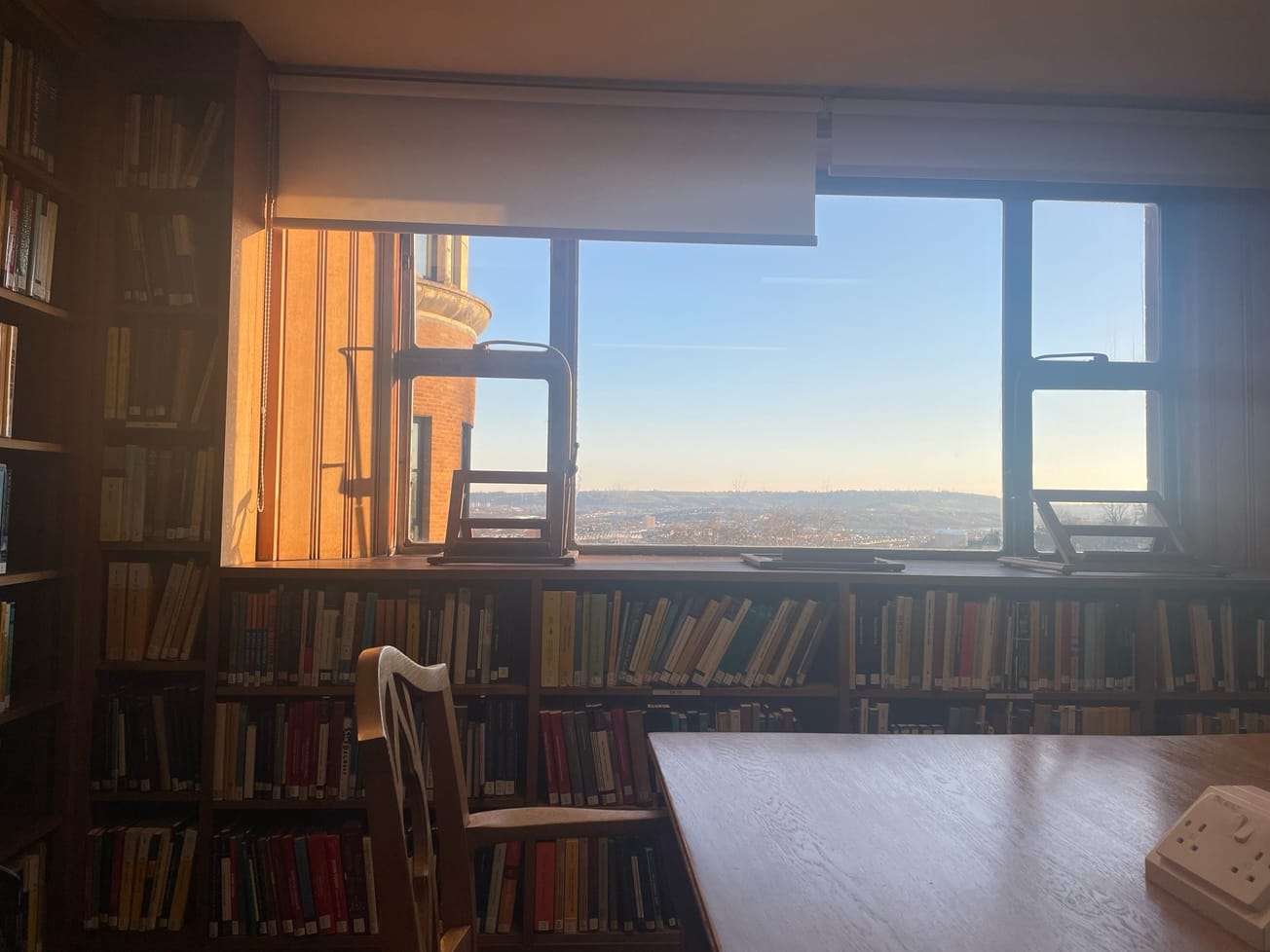

Featured Image: Epigram / Ellen Jones

Have you felt the pressure to secure work experience impacting your studies?