By Milan Perera, Arts Critic Columnist

In an instalment of Desert Island Discs, the comedian and writer David Baddiel spoke of the absence of his father at his graduation from Cambridge with a Double First in English and Politics. Seeing the incredulity of the presenter Kirsty Young, Baddiel apologetically added that his father thought that arts and humanities are a “waste of a brain”.

The above sentiments and the strength with which they are expressed are not uncommon in today’s climate, with some universities folding many arts and humanities degree courses in favour of those perceived as hot favourites among top employers. For example, Sheffield Hallam University has decided to withdraw its standalone English Literature degree, a year after University of Cumbria took a similar action, much to the dismay of writers such as Philip Pullman and James Graham.

Michelle Donelan, in her short stint as the Minister of State for Higher and Further Education, said that the government recognised all subjects, including Arts and Humanities, can lead to positive student outcomes. But she went onto add that “Courses that do not lead students on to work or further study fail both the students who pour their time and effort in, and the taxpayer, who picks up a substantial portion of the cost.”

According to the latest statistics, Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) acceptances for English studies, including English literature, plummeted from 9,480 in 2012 to 6,435 in 2021.

So, is a degree in Arts and Humanities nothing but a waste of time and energy that seems far removed from the existential challenges of the current zeitgeist?

The Pulitzer Prize winning journalist George Anders points out that there is a huge shift even at the hubs of science and technology, such as Silicon Valley, towards Arts and Humanities degrees: “Uber was picking up psychology majors to deal with unhappy riders and drivers. Opentable was hiring English majors to bring data to restauranteurs to get them excited about what data could do for their restaurants,”

He further points out that “I realised that the ability to communicate and get along with people, and understand what’s on other people’s minds, and do full-strength critical thinking – all of these things were valued and appreciated by everyone as important job skills, except the media.”

The above realisation led him to pen the critically acclaimed book “You Can Do Anything: The Surprising Power of a "Useless" Liberal Arts Education”. The key skills one learns through Arts and Humanities degrees: curiosity, creativity, and empathy are not unruly and anachronistic nonsense that must be reined in, but qualities vital to every facet of our lives, including future employment opportunities.

For example, as a graduate in English, one can thrive in sectors such as administration or sales. You can segue from anthropology into the booming new field of user research; from Classics into management consulting, and from philosophy into high-stakes investing. Many playmakers in tech industry are looking for a humanist’s grace to be applied to rapidly evolving high-tech future.

The best-selling author Philip Pullman points out that: “Without literature, without music and art and dance and drama, people young and old alike will perish of mental and emotional and imaginative starvation. We really do have a government of barbarians.”

To treat Arts and Humanities degree courses as “interesting” or “cool” reduces them to the reserve of a certain social strata; it should not be a luxury for a wealthy minority and privileged aesthetes.

Epigram had the opportunity of interviewing the esteemed art valuer and auctioneer Nick Bowkett regarding the renewed interest in the sector to recruit more Arts and Humanities graduates to bring some much-needed vibrancy and vitality to an industry which is considered the reserve of “White old men from privileged families”.

Mr Bowkett pointed out that: “The auction business is unusual as it embraces, even celebrates age, generally speaking, the older you are, the more knowledge you accumulate. One of my favourite sayings is “the more you learn the more you earn”. Simply put, your career is likely to have longevity, be flexible, financially rewarding and be less susceptible to AI than many other professions.”

A specialist knowledge in history or history of arts come in extremely useful in the antiques and auctions sector. He further elaborated that:

“The list of categories you can specialise in is endless, traditional areas to name a few include, coins, jewellery, medals/militaria, classic cars, stamps, ceramics, Asian Art. Other areas could include modern collectibles such as Star Wars, comics, Pokémon cards etc.

Specialising is fine but aging auctioneers like myself find it difficult to recruit young people willing to become general valuers who are often the first point of contact when visiting customers, I have to have a very good general knowledge of value for virtually everything in someone’s house! At Stroud Auctions we have multiple experts we can call on for specialist sections but being able to value generally is a very sought-after skill.”

“We are also lucky to have a good range of young and old, I love the dynamics of the young people learning from the more experienced members of staff, who are often delighted to pass on decades of experience.”

“You often find auctioneers specialising in areas they collect in or have a passion for themselves. Like all jobs, the more effort you put in, the more rewarding it becomes, it is possible to arrive from University to work for us on a basic starting Salary, show promise, initiative and enthusiasm and achieve multiple pay rises very quickly.”

“Let’s imagine someone comes to work for us, they could specialise in anything, coins, vinyl records, cameras, toys etc, they proactively seek consignments with innovative advertising strategies, join online groups, engage with relevant collecting communities, visit trade fairs, generally work really hard.”

When we asked about the incentive for Arts and Humanities in antiques trade, Mr Bowkett is of the opinion that: “If you can grow your particular section from say £100k per specialist sale to £200k over a few years you suddenly become a very valuable employee, you would be rewarded with higher pay, increased advertising budget, your job starts to become easier, sales increase further. I have made it sound easy and in reality, the number of people who go the extra mile to achieve that type of success are about one in five.”

Mr Bowkett firmly believes that all of us in our respective occupations and vocations should “do their bit” to save the planet from an existential threat. For him the sector of antiques and valuables has the least carbon footprint: “Auctioneering and valuing can be very rewarding as, unlike dealing you are trying your level best to get people the most money for their items, also, done properly, it’s also one of the greenest professions, virtually everything we sell is second hand! The carbon footprint of a Victorian chest of drawers is zero, it’s probably had eight owners!”

At this encouraging pronouncement it seems that a degree in Arts and Humanities is not a waste of money, time and effort, but a sector that will continue to thrive in the light of developing technology and climate change.

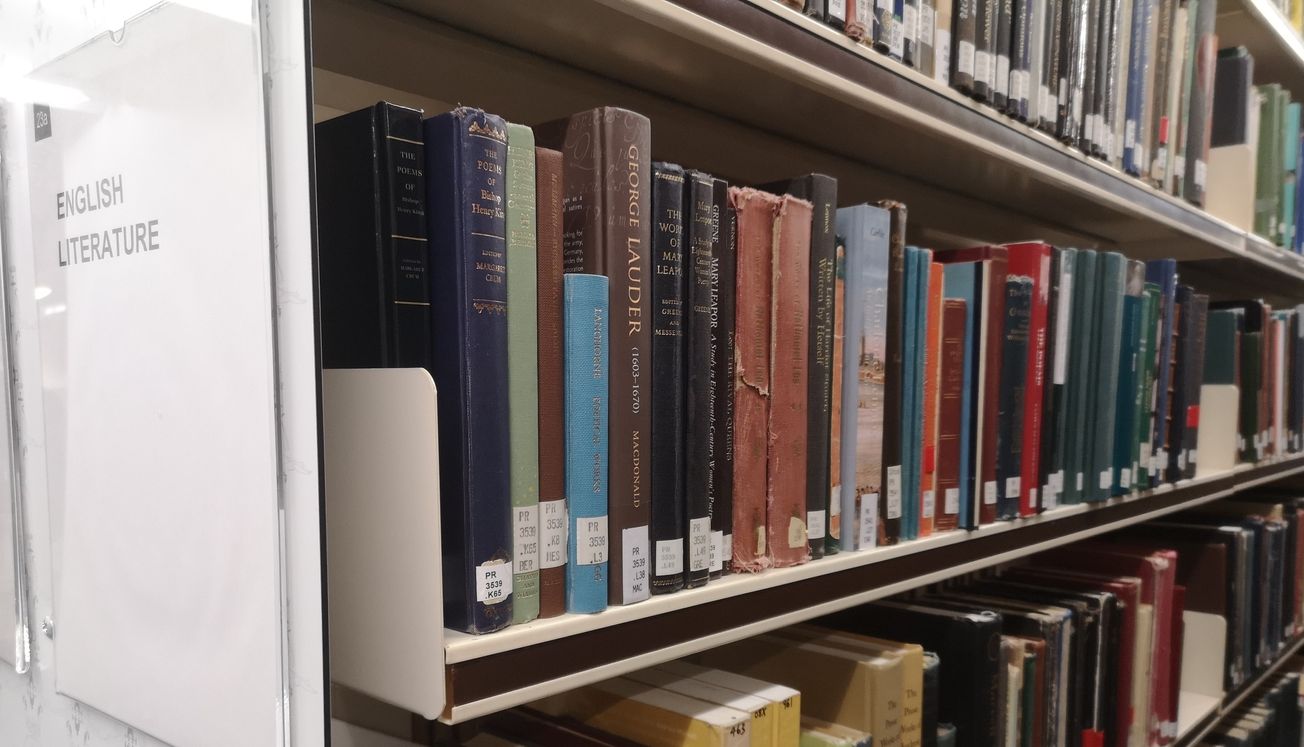

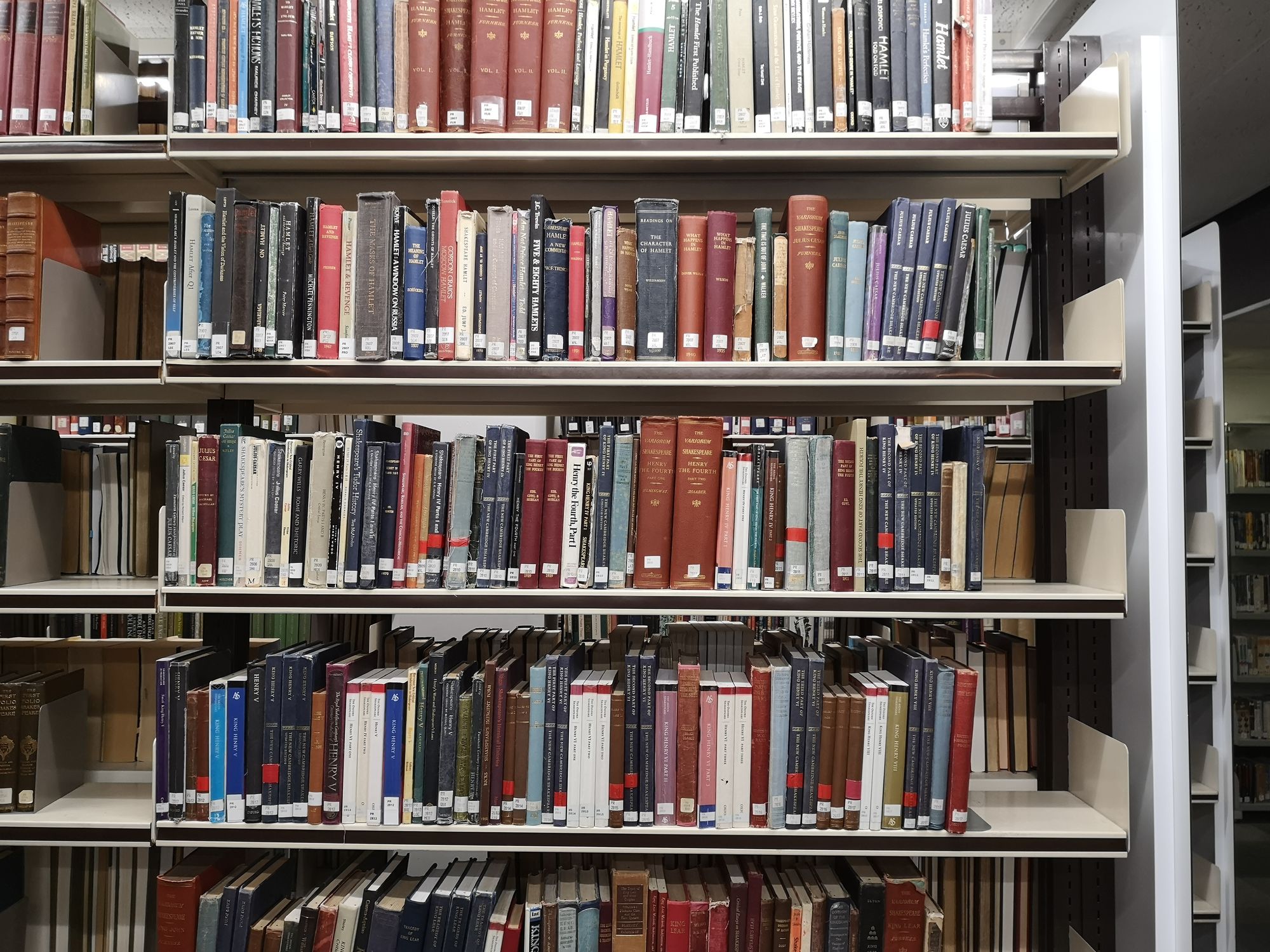

Featured Image: Courtesy of Milan Perera

Why do you find Arts and Humanities degrees important?