By Mihai Roşca, Second-year, Sports Subeditor

I was scrolling Instagram when I was surprised to see the popular page ‘Pubity’ posting something about our University. Their post had over 339K likes and was referring to some kind of ‘nuclear-powered diamond battery’.

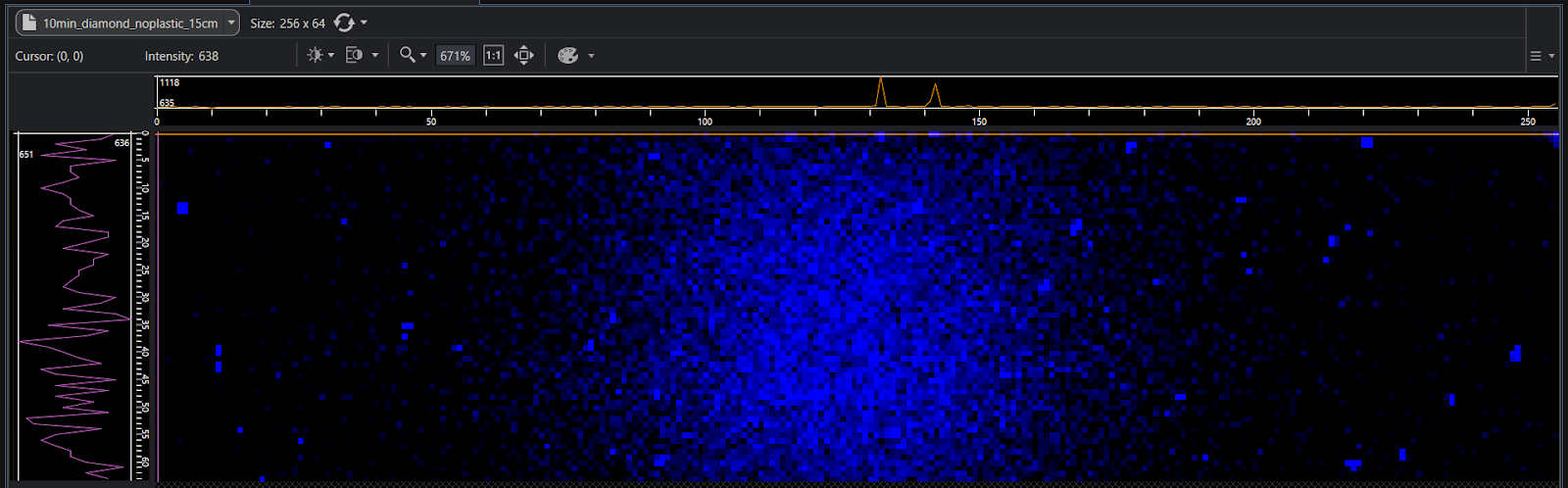

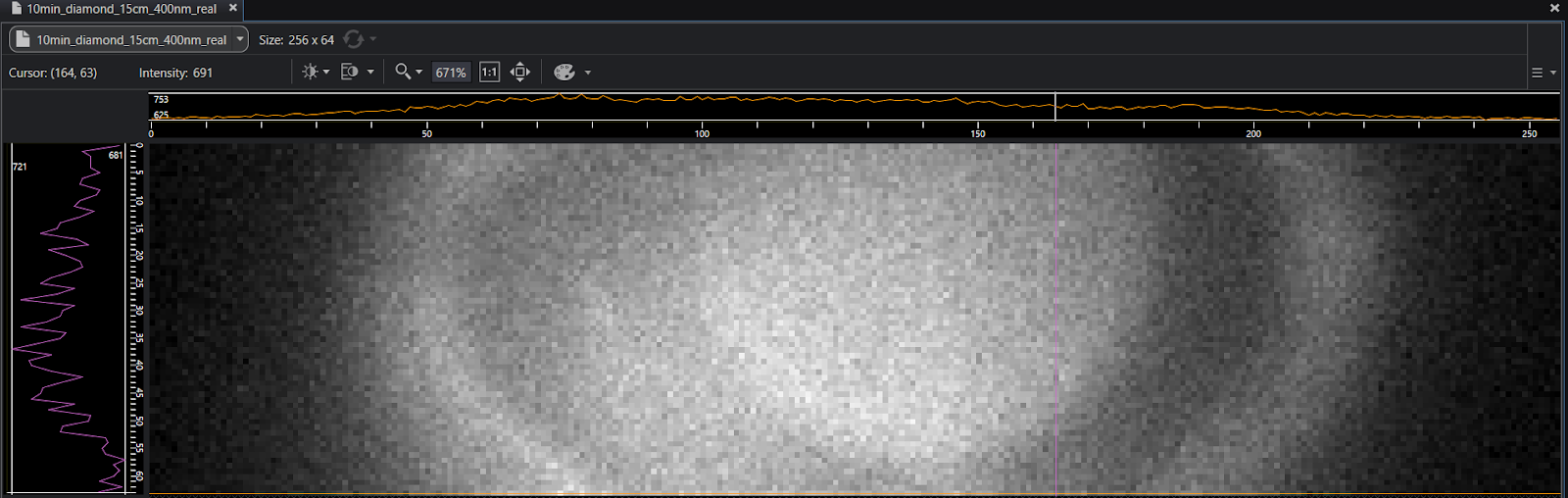

I was pleased to see that last month’s ‘From the desk of:’ featured the University of Bristol’s team of scientists who developed this ‘diamond battery’. The team worked with researchers from the UKAEA (UK Atomic Energy Agency) to make a battery made from a radioactive material known as Carbon-14 encased in a thin layer of diamond. The Carbon gives out a comparatively small amount of energy that is much less than even a double-A battery. The upside is that these batteries can keep churning out the energy for tens of thousands of years.

The new invention has caused a stir for its simplicity, and its durability means it will be found to be useful in a number of applications including at work in extreme environments like space and underwater.

Recently, Epigram had the opportunity to speak to the researchers here in Bristol to clear up some misconceptions and shed more light on their buzz generating invention.

Neil Fox and Tom Scott originally came up with the idea of the device while working on a research project from EPSRC (Engineering Physical Sciences Research Council). The research council gave them ‘a grant to look at semiotic energy conversion’ where they were specifically tasked to consider whether they ‘could do this bootstrapping of performance by using Carbon-14’.

Right off the bat I’m corrected for referring to the device as a ‘battery’; ‘technically, if you talk to engineers they’ll say that it’s a harvesting device.’ Nick explains, ‘this is a solid state device, whereas most batteries are chemical devices’. James suggests that their device has become known as a battery because it’s easier for a layman to understand it as a battery - a familiar concept - rather than a harvester which the writer would have to explain.

They didn’t seem to be aware of the virality of their research, nor were they very much bothered by it. They told

Epigram their goal was and always will be to do ‘good science’ and ‘get the material made’.

I kept reading online that their device might be used in pacemakers so they wouldn't have to be changed so often. They said that while it was a consideration it wasn’t ‘a near-turn application’, because ‘certification for that sort of technology, you’re looking at almost a decade to get that into place’. Instead, they’ve chosen to focus on immediate application; the durability of the harvester means it can be used to tag things in space to say whether the object is junk, useful, or something else entirely.

They tell me it was a ‘team effort’ to get the device made. For example, some PhD students tested out concepts in the reactors. The work for the battery took 5 years (2019 to April 2024) to yield the desired result so I can only assume that all the help was gladly appreciated!

It’s definitely interesting to hear how Covid influenced the research process and student lives. ‘I think we would have had a lot more students getting involved if we didn’t have lockdowns’

But I’m once again impressed, the scientists managed to make the best out of a bad situation: ‘We were always talking on Zoom or Teams and we’d have conversations about what we need to achieve and come up with various different designs and work through them. In some ways we were fortunate it happened during Lockdown because it gave us time to think’. Neil adds that most of the problems that arose were practical, rather than theoretical. Possibly because they had already worked out through the ideas.

The team’s next plans are to continue the project with a tritium element instead. They think that it could have even more applications than the Carbon because it has an output 50 times bigger; it is cheaper (Carbon-14 is £40,000 a gram) and because devices sold with tritium should have fewer restrictions placed on them.

Epigram’s conversation with these wave-making scientists really goes to show the immense productive capacity of the university, which very few of us even realise!

Featured image: Dr Neil Fox