By Lucas Mockeridge, SciTech Deputy Editor

Facial recognition seems relatively benign. No harm comes from using it to unlock a mobile device, or pass through an ePassport gate at the airport. But the technology is also used for state surveillance, even in Britain.

The UK police first trialled live facial recognition as a surveillance tool in 2014. Since then, several police forces around the country have gradually adopted it and now, controversially, the Home Office is hoping to expand its use nationally.

Under live facial recognition, footage from CCTV and body-worn cameras is streamed directly to the police’s facial recognition system in real time. The system finds faces in the footage and compares them with those on a police watchlist. Officers nearby are alerted if there is a match.

Modern facial recognition systems owe their remarkable accuracy to a type of artificial intelligence called deep learning. Deep learning revolves around deep neural networks: algorithms inspired by the human brain that learn to perform tasks by creating patterns from data.

Facial recognition systems often use neural networks for face detection. A network first receives a dataset of images, with the locations of the objects and faces within them. Using this data, it learns a series of filters that can be applied to an image to find all of the faces that it contains.

Neural networks are also used to recognise faces. For this task, a network is given lots of cropped images of faces. By telling it which faces it must regard as the same person, a network can learn to distil the essence of a face into a vector, which can then be used for comparisons.

To make sure that the network finds important facial features, faces in the data must vary as much as possible, from pulling funny expressions to wearing face coverings. Moreover, the faces must be diverse to prevent the network from being inherently biassed.

Bias has been a huge issue with facial recognition systems historically. In 2019, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology found that many commercial facial recognition systems were 10 to 100 times more likely to misidentify a black or East Asian face than a white one.

However, the National Physical Laboratory found that the police’s live facial recognition had no race or sex bias under certain system parameters. But the chances of a false match was one in 6,000. At that rate, tens of thousands of people could be misidentified on a national scale.

The police believe that live facial recognition helps them to prevent crime from happening and bring criminals to justice. For instance, a wanted sex offender was arrested at the Coronation, after being identified by the technology.

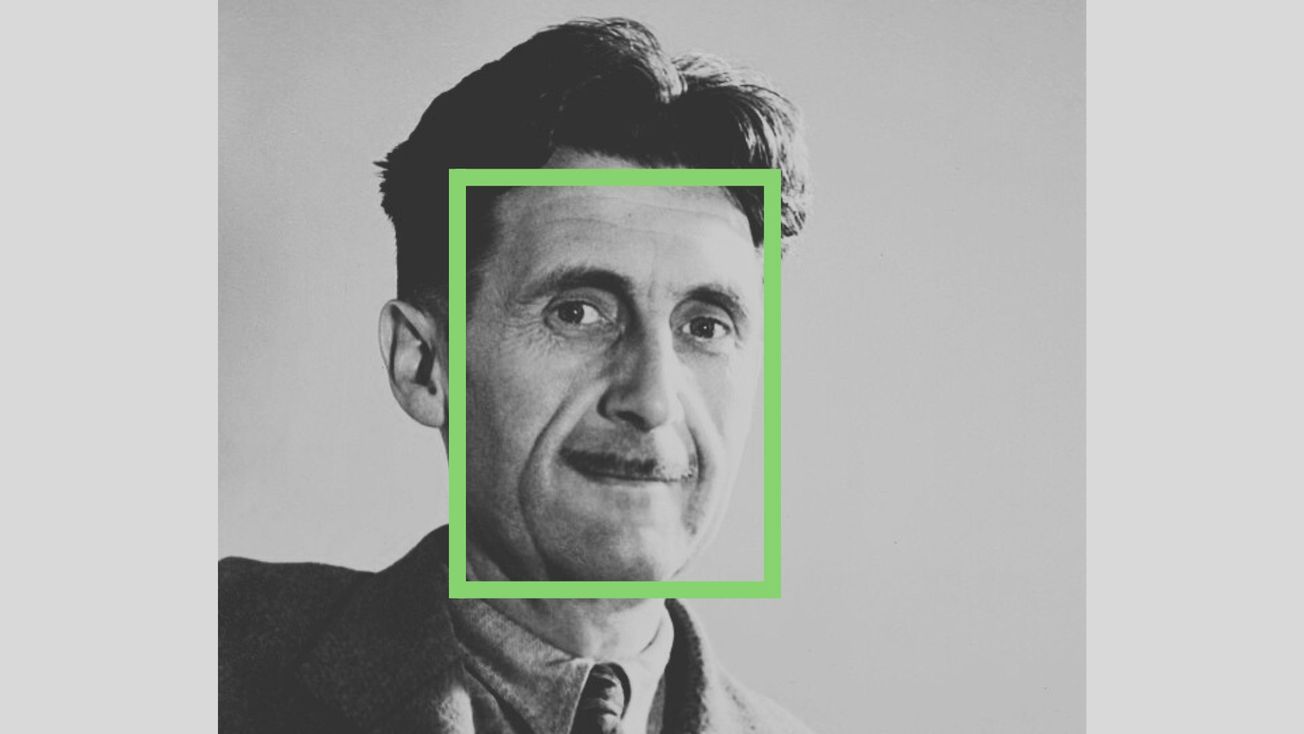

Human rights groups describe the technology as ‘Orwellian,’ and compare the police’s use of it to taking DNA or fingerprints without consent or even knowledge. They accuse the police of turning Britain’s streets into police lineups, and Britons themselves into walking ID cards.

Campaigners also argue that live facial recognition undermines the presumption of innocence, the bedrock of liberty and justice. They believe that once an individual has been identified by facial recognition the onus is on them to prove their innocence rather than the state to prove their guilt.

Whilst the EU is moving to ban police from using live facial recognition, the UK has no law that even mentions it. The police are able to justify its use under common law powers, but the public expect the law to be explicit.

Research by the Ada Lovelace Institute found that the majority of the British people want police use of facial recognition technology to be restricted, and nearly a third are uncomfortable with it altogether. People's discomfort was often tied to a fear of normalising surveillance in Britain.

This fear may be well-founded. Britain has around six million CCTV cameras, each of which could be connected to a live facial recognition system. The technology has already been used by other countries to stop people from protesting, and to persecute minority groups.

An expansion of live facial recognition may irrevocably change the relationship between the state and the individual in Britain. Perhaps this would create more injustice than any set of criminals could ever visit upon society.

Featured image: Flickr / Cassowary Colorizations

Are you comfortable with the police using live facial recognition?