By Lola Nelson, Second Year English

Have you ever glanced up from your laptop after long, winter hours spent in the library and taken a look around? If so, what have you noticed? Has it been the countless sea of students lining the desks, cramming the night before a quiz or seminar, or has it been something else? For those with an interest in all things creative, the buildings associated with the University of Bristol are a gold mine of fascinating artwork and historical narrative portraiture that tells stories and provides clues to the university’s history. In this article, I will explore the frames that frame the university’s history, taking you on a journey through the fascinating and accessible archives that linger in plain sight.

It only seems right that the first location I explore is Bristol’s prominent Neo-Gothic location, the Wills Memorial building. The building, established in 1915 and said to be one of the final great Gothic buildings built in England is a work of art in itself; its striking tower soars above the city, visible from multiple other viewpoints, whilst its interior only enhances its enchanting Gothicism. Upon ascending the stone steps and turning around, you are faced with the towering stained-glass window. On a stone arch opposite the window is a diagram of each detail or ‘arm’ on the window. The artwork acts as a heraldic guide explaining the coats of arms displayed on the tower’s window. The shields are arranged by compass direction, and when combined, tell a story. The university is rooted in the city, the region of Somerset, and the Wills family that made it possible.

Upon entering a corridor to the Wills’ bustling study hall, a large painting comes into view on the left side. It depicts a calming pastoral scene in which horned cattle wander across a rocky landscape. The painting itself takes up room and has always caught my eye when I decide to study in the building. The image, painted by Henry William Banks Davis (1833-1914), is appropriately named ‘Cerig Gwynion, Radnorshire’, which when translated from Welsh roughly becomes ‘white stones’. In addition, Radnorshire is a historic county in Wales, now part of the county of Powyrs. The artist was well-known for his pastoral scenes influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, though later settled into a more personal style. Now that we’ve broken the plaque down, what does this painting mean and why is it on the wall of the building’s busiest corridor of students? The rural image places emphasis on the land and history of neighbouring regions, valuing continuity between the past and the present: although painted over a hundred years ago, the scenery is timeless. The imagery of the cattle crossing the rocky terrain additionally makes me think of students’ journey through their time at university, most likely ridden with ups and downs but eventually becoming a beautiful scene which they can reflect upon later on.

‘This sculpture is a crucial part of the university’s selection of art, aligning the university’s values in celebrating scientific achievement and those behind it’

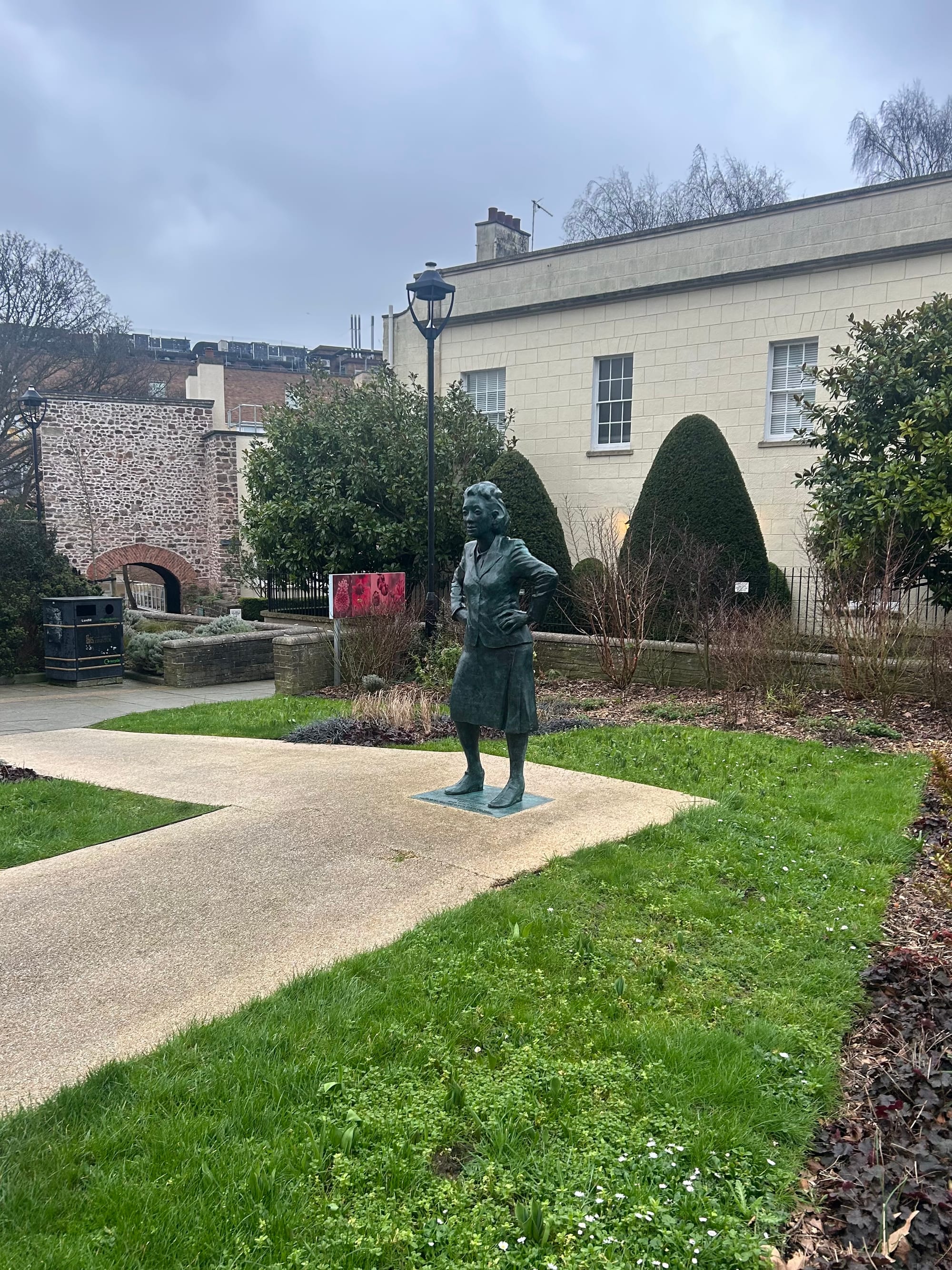

Sculptures are also prominent on campus, such as the bronze statue of Henrietta Lacks by Royal Fort House and Gardens. The statue, created by landscape gardener and sculptor Helen Wilson Roe is situated in the centre of a meticulously designed garden and depicts Henrietta Lacks. Lacks’ HeLa cells became a crucial tool in modern medical science. Taken without her knowledge after her death at the age of 31, her cells have helped enable breakthroughs from cancer treatments to vaccines. For decades, however, her name and story were largely unknown. The garden itself places Lacks at the centre, with flowers chosen specifically for symbolic colour, resilience, and renewal. The plaque tells us that ‘the Alium Red Mohican refers to her indigenous American ancestry’; we are also informed that all the selected flowers and plants are red - her favourite colour. This sculpture is a crucial part of the university’s selection of art aligning the university’s values in celebrating scientific achievement and those behind it, ultimately creating a space that values reflection, responsibility and justice in research.

The Royal Fort Gardens contain various other sculptures and works of art that remain hidden in plain sight. Amidst shrubbery and trees is the bust of Humphry Repton (1752-1818), an English landscape gardener who redesigned the Royal Fort Gardens in 1799, by ‘sculpturing the land’. Interestingly, Repton coined the term ‘landscape gardener’ in 1788 to describe his profession. He used the title to outline his work which combined artistic design with functional gardening. In order to help clients envision his visions, Repton created ‘red books’ which depicted his designs in a flurry of watercolour, sketches and text.

Students who spend time in the Queen’s Building Library may be familiar with some artworks hanging around its interior. A large charcoal drawing depicts the monochromatic view of a bridge over water, named ‘Bridge over the Avon Cut as seen from Brunel Way’, donated by the artist, Elizabeth Timms. The image captures a quiet industrial stretch of Bristol, grounding the Queen’s Building in its wider city landscape. An interesting frame that stands out is a black and white photograph of Winston Churchill in 1929 which depicts a mock arrest of the past Prime Minister by students, taking him to the Victoria Rooms for a mock trial on RAG Day, a student charity fundraising event.

Although there are countless other works of art and history alike lining the university’s walls, the beauty is precisely that they are there to be found. Although I would love to explore every single work in this article in detail and honour of the artists, I believe one of art’s exciting features is its purpose to be explored and interpreted. Next time you are studying or finishing off the final paragraph of that essay you probably should’ve started two weeks ago, take a breath, look around, and see what art you can find.

Featured image: Queen's Building | Epigram / Ella Heathcote

Have you ever noticed the artworks around campus?