By Gaby Turner, Comparative Literatures and Cultures MA

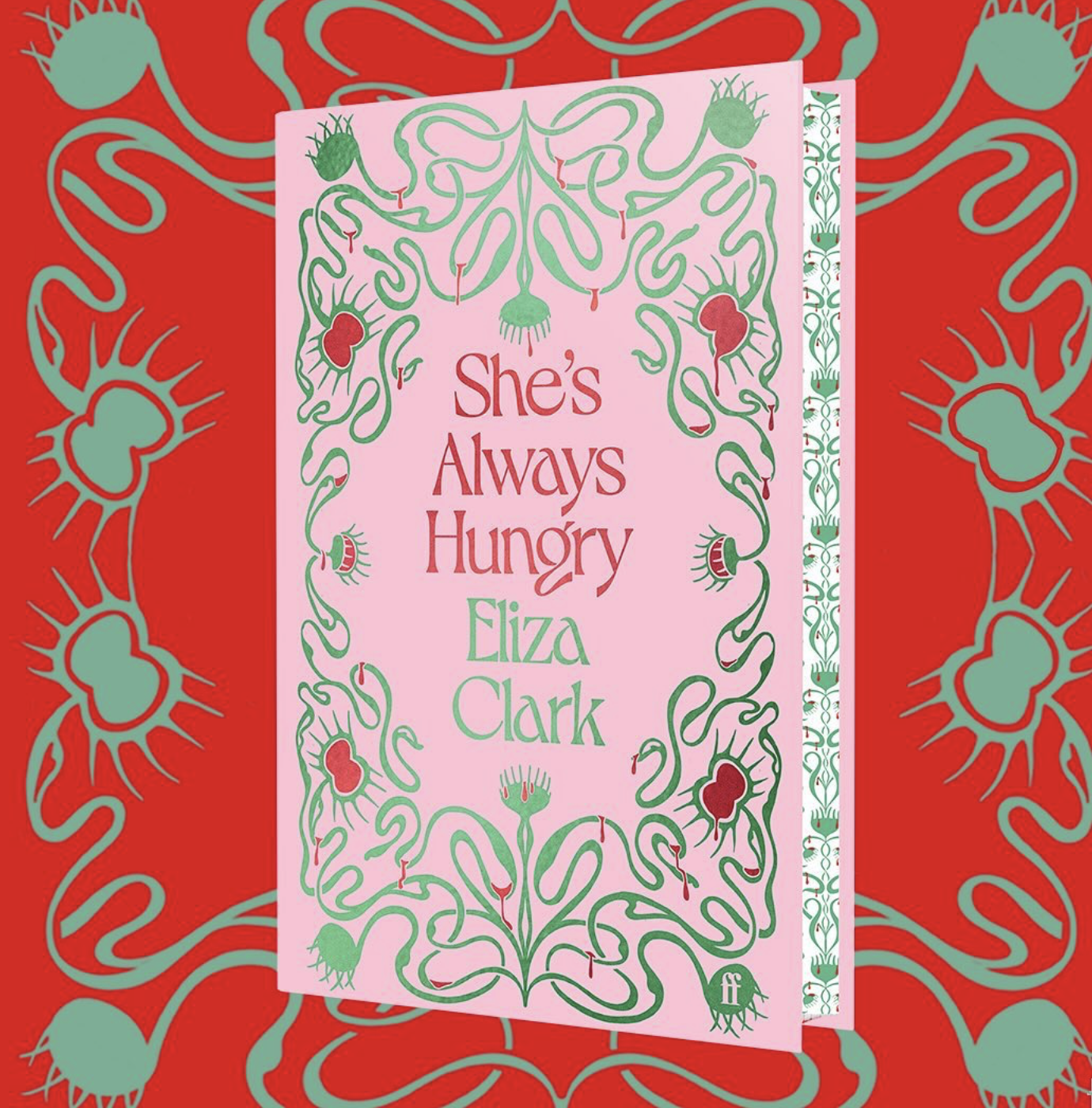

On a cold Tuesday evening, the Bath Elim church fills with women in their best, semi-gothic, outfits eagerly waiting to listen to novelist Eliza Clark. Clark has recently been labelled ‘a bona fide queen of body horror’ (The Guardian) and is out promoting her newly released short story collection, She’s Always Hungry. She'll be visiting a series of independent bookshops which includes Bristol’s own Bookhaus.

The event in Bath, hosted by Mrs B’s Emporium, took place in the nearby church, where Clark sat down with writer Julia Armfield to talk about the collection. The two joked about the setup of the event, as it appeared somewhat like a fireside chat, a celebration of life for a (very much alive) Eliza, or even a summoning of demonic energy. It’s clear to see the dark sense of humour that pervades Clark’s fiction.

Clark’s first novel Boy Parts (2020) seemed to coincide with the rise of BookTok, gaining her a major audience and widespread attention did not end there. 2023 saw Clark named one of Granta’s Best Young Novelists and Boy Parts adapted into a Soho play. In my own experience, it was so addictively good that I found myself rushing through the rest of my day just to have more time to read it. But, with fame comes criticism and for Clark, this means the constant accusation of chasing shock value. Looking back on her development as a writer, she acknowledges that several particularly gory elements of Boy Parts were in fact there to shock. She partly attributes this to her experiences at art school which she attended while writing her first.

She goes as far as to call the work juvenilia, the product of a writer in her early 20s, who was simply ‘not done cooking’. However, she is quick to point out how limited this critique is: ‘If you want to engage with me as a shock artist, you can but you have to ignore vast swathes of my work’ she argues, adding ‘but that hasn’t stopped the British press.’ In particular, she talks about a scathing reviewer who actually claimed that Boy Parts had almost caused them to vomit on the London Underground. ‘As if that’s a bad thing’, she jokes.

It’s clear that Clark does not let criticism get her down, showing an understanding of the traps of literary culture. For her, Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface (2023) does an excellent job of showing how publishing ‘picks a winner.’ Whilst she does not deny the benefit of this (admitting that Granta brought her work some needed attention) she points out the hypercritical attention which prize culture brings on, calling it ‘open season’ on the winner. It is worth considering how openly these two young female novelists, Clark and Kuang, discuss this. It begs the question of whether they, as a demographic, experience more criticism than their older or male counterparts, or whether they are evidence of a growing skepticism towards the infrastructure of publishing.

Turning the spotlight on writers themselves, she rejects the claim that writers are ‘burned-out, former gifted kids’, instead telling a story of still ‘horrendously competitie’ authors who will cry when they don’t win. It’s a caricatured image of the writer who is still obsessed with academic validation, but one that is refreshing to hear from someone in that world. Interestingly, Clark often returns to the economic dimensions of literary fame, confessing her disappointment that the Granta recognition did not itself come with a financial reward. This raises an important question of the viability of artistic production under economic strain.

She’s Always Hungry picks up on a recent craze for body horror in the culture. We can see this more in relation to cinema, with the huge success of films like The Substance (2024) . It's a testament to the influence of cinema on Clark. She’s hugely inspired by Asian horror, manga, and K-cinema. She wants you to know that she knew about Bong Joon-ho before Parasite! She envisions She’s Always Hungry as a splatter film.

Luckily, Eliza shares little else with the violent and narcissistic protagonist. The author who speaks with humour and warmth, and the beautiful pink hardcover of her collection, provide a fascinating contrast with the violence of her work. Her interest in body horror connects a taste for the morbid to a more general fascination with the body. Clark confesses that she often feels ‘trapped in my flesh prison’ and doesn’t really want a body. It’s not surprising then, that the body becomes the ultimate source of horror in her work.

Alongside cinema, Clark is also greatly influenced by the world around her from news, to social media, and lived experience. One particular story in this collection ‘The Problem Solver’, was loosely based on the infamous Liam Neeson interview (2019) in which he discussed his own irrational and racist response to hearing of the assault of a female friend. Another, ‘Little Chitaly’, was hilariously born out of Clark’s obsession with the Takeaway Trauma Instagram account.

Subverting the horror genre, She’s Always Hungry challenges the expectation of fear. The characters in Clark’s world ‘give themselves over to horror’, she says. Considering fear a relatively flat emotion, she argues that neutral, positive, or even comedic responses to horror are much more interesting to read and watch. Once again, these characters are a stark contrast to Clark herself, who cites the fear of death itself as a more abstract motivation for her writing.

Her subversion of the horror genre also recognises its gendered dimensions. Women are huge consumers of horror (which became extremely clear from the demographic of the room) yet often find themselves the victims of its violence. In general, she seeks to complicate the narratives of passive victimhood or the veneration of the good-girl survivor which dominate the horror genre. Instead, she refers to her writing as a reclamation of the perpetrator role for women.

The short story is sure to thrive in an age of diminishing attention spans. It’s also a chance for young writers like Eliza Clark to demonstrate their incredible range. She’s Always Hungry deals with a range of contemporary issues, from climate change to gender violence.

Yet, at the same time the work stays true to her self-proclaimed writerly interests: ‘the politics of power and desire…. and food’.