By Miranda Smith, third year History of Art

The sketches and studies of Renaissance master form an interesting, though underwhelming, exhibition. Miranda Smith gives context and reviews.

The exhibition at the Bristol museum and gallery houses some of Leonardo da Vinci’s five hundred drawings, which are currently on exhibition around the country in a joint spectacle celebrating five hundred years since the artist’s death. They are ordinarily kept at Windsor castle in storage where light cannot damage the works. After the closing of the regional shows, all five hundred of the drawings will be displayed together at the Queen’s gallery in London.

The opening text of the exhibition explains that Da Vinci drew not only to prepare for his painted canvases, but also to record the world around him, to pursue his scientific speculations and to make visible the workings of his imagination. His drawings range from anatomical illustrations for a proposed treatise, to botanical studies, and images of fantastical beings. Though several of them were made for specific paintings, the minute detail makes them works of art within their own right.

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing | Bristol Museum & Art Gallery https://t.co/nVppTeQWBE #leounfinished

— Bristol UK Info (@Bristol_UK_Info) February 7, 2019

His anatomical drawings are renowned for their accuracy – he measured the proportions of real life models, both living and dead, and performed dissections to gain insight into the workings of bones, muscles and tendons. His sketches are accompanied by scribbled notes detailing the mechanisms of the human figure. The drawings were working papers meant solely for his own study, never intended to be exhibited as they are. His final campaign was relating the workings of the heart, where drawings of each ventricle and the various arteries that join to them are present alongside text explaining the purpose of each.

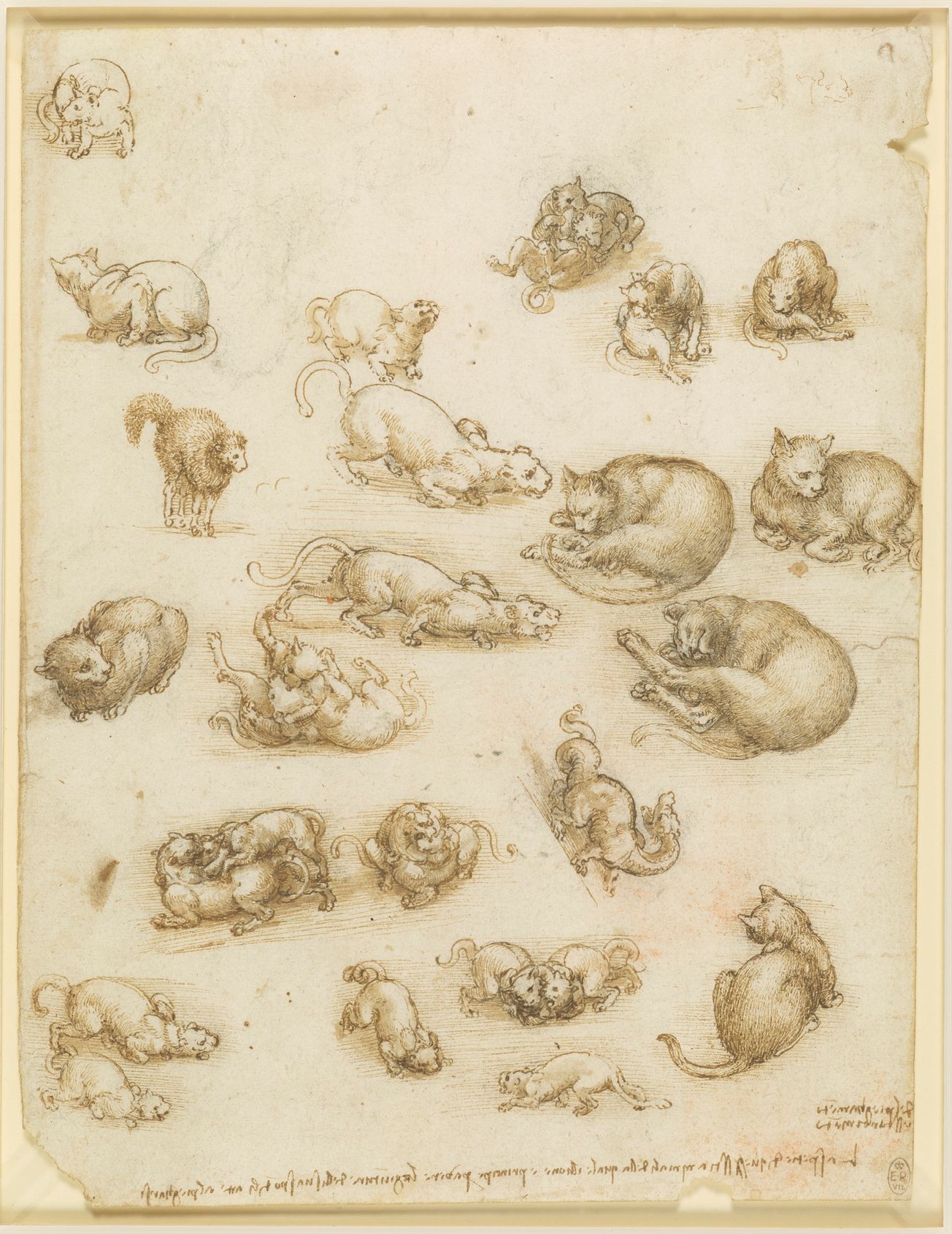

He also compiled studies of animals, particularly cats, and supposed that “of flexion and extension - the lion is prince of this animal species because of the flexibility of its spine.” This focus on movement is most apparent in preparatory sketches as the lines of the limbs are often blurred with several options for the positioning of the parts before he decided upon the final pose. His preparations for an equestrian portrait also consist of this.

Leonardo da Vinci's 'The head of Madonna' c.1510-15. Image credit: Royal Collection Trust / Her Magesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The botanical studies were originally drawings for ‘Leda and the Swan’, but he was also planning a treatise of the structure of plants and trees. The detail of the sketches is considerably more than necessary for just a preparatory sketch.

His vivid imagination is evident not only in his interest in engineering and the invention of mechanical instruments, but also by his illustrations of imagined creatures. Some of these drawings date to his time working as court artist in France where, as well as painted canvases, he created designs for costumes and stage sets.

Towards the end of his life, the artist became obsessed with death, drawing images of a cataclysmic storm devastating the earth, linking to his realisation of the impermanence of life. These images acted as a summary of his career – the attempt to get out onto paper the forces of the universe.

"the viewer is left disappointed by the changing focus"

The second room of the exhibition is anti-climatic, with the museum attempting to thematically link his drawings to modern pieces. There is a particular focus on ideals of beauty. In my opinion they are taking too political a stance, removing the focus from his study of the world around him and bringing it more towards a lack of inclusivity. There are more relevant questions regarding whether viewers value sketches less than completed paintings, and whether or not we should celebrate our failures - the majority of Da Vinci’s paintings were never completed, or abandoned.

Whatever impact this second room has is lost as the viewer is left disappointed by the changing focus. It seems to insinuate that Da Vinci is just an ordinary man - that many others have focused on movement, on the tools of humanity, and on the human form - rather than maintaining the focus on his genius.

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing is free to students on Wednesdays and runs until 6th May.

(Featured image:Leonardo da Vinci's 'Cats, lions and a dragon', c. 1517-18. Featured image credit: Image credit: Royal Collection Trust / Her Magesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019)

Have you seen da Vinci's work in Bristol or beyond? Let us know in the comments below or on social media.