By Ursula Glendinning, Wellbeing Deputy Editor

The Croft Magazine // After a difficult few months, Ursula deleted her public social media and picked up a book on nature literature. What followed was a radical change of perspective. Ursula examines how social media warps our outlook.

Until relatively recently, when I wrote about mental health, I frequently referenced the Internet. My regular citation of problematic trends or referrals to high-flying commentary accounts had become integral to my perspective. This world, constructed of bytes and hashtags, that our generation has carved out for itself, feels three-dimensional to those who become emersed in it.

At the beginning of last year, I descended into the depths of break-up fuelled depression from which I struggled to re-emerge. To compensate for the loneliness, I drowned myself in the pseudo-camaraderie and busyness of social media consumption. When I wasn’t working, I filled my hours scrolling. However, this wasn’t sustainable. Around March of that year, I moved into a different household, and it was then that I discovered nature literature.

It is hard to talk about the impact of poetry and literature in a way that hasn’t been done before. Jeanette Winterson describes in her memoir, Why be Happy When You Can be Normal, how she read a segment of T. S. Eliot’s poetry, “This is one moment, / But know that another / Shall pierce you with a sudden painful joy”, and immediately began to cry. My introduction was not nearly as climactic. I had not been starved of literature as a child, far from it, I had the privilege of growing up in a household among academics. I was practically smothered with the stuff, and I loved it. I ate up all that I could get my hands on. What I mean to say is, my introduction to literature could never be characterised as accidental or emotionally obliterating. It was integrated into my childhood seamlessly, and for that I am thankful. But its power was therefore somewhat glossed over.

A fascination that began with Elizabeth Bishop’s works moved swiftly onto the likes of Robert MacFarlane and Helen MacDonald. This literature had a profound effect on me. Funnily enough, the medium that so many use as a distraction from life brought life back to me. I was suddenly wildly present. The world around me took on a vitality I hadn’t seen since I was a child. I recovered a wonder of the natural world that we lose as we grow and become increasingly engrossed in capitalist and materialist necessity. When I walked, I took my headphones out and spotted buzzards and golden plovers. Granted, this was made possible by living in and among vast swathes of moorland. But, even in the local village, I could recognise the trees and plants that frame the post-industrial landscape. When you can identify something and give it a name, it moves out of redundancy and into your periphery.

Later that year I deleted TikTok (I intend to gradually delete most of my social media) and with it, I believe my perspective has transformed. Our truths, however they transpire (for they all emerge from something), are informed by, and become interchangeable with, our outlooks. Online these truths can be transmitted, sometimes beautifully. But online discourse has become a beast in and of itself. With such trends as #NoNuanceNovember and cultural commentary accounts, content consumers feel they are discovering new ways to view the world all the time. It has become easier and easier to find critical takes on microtrends, TikTok poetry, and the effects of mass media consumption.

But by distancing myself from this pseudo-world, I realised something: it does not matter.

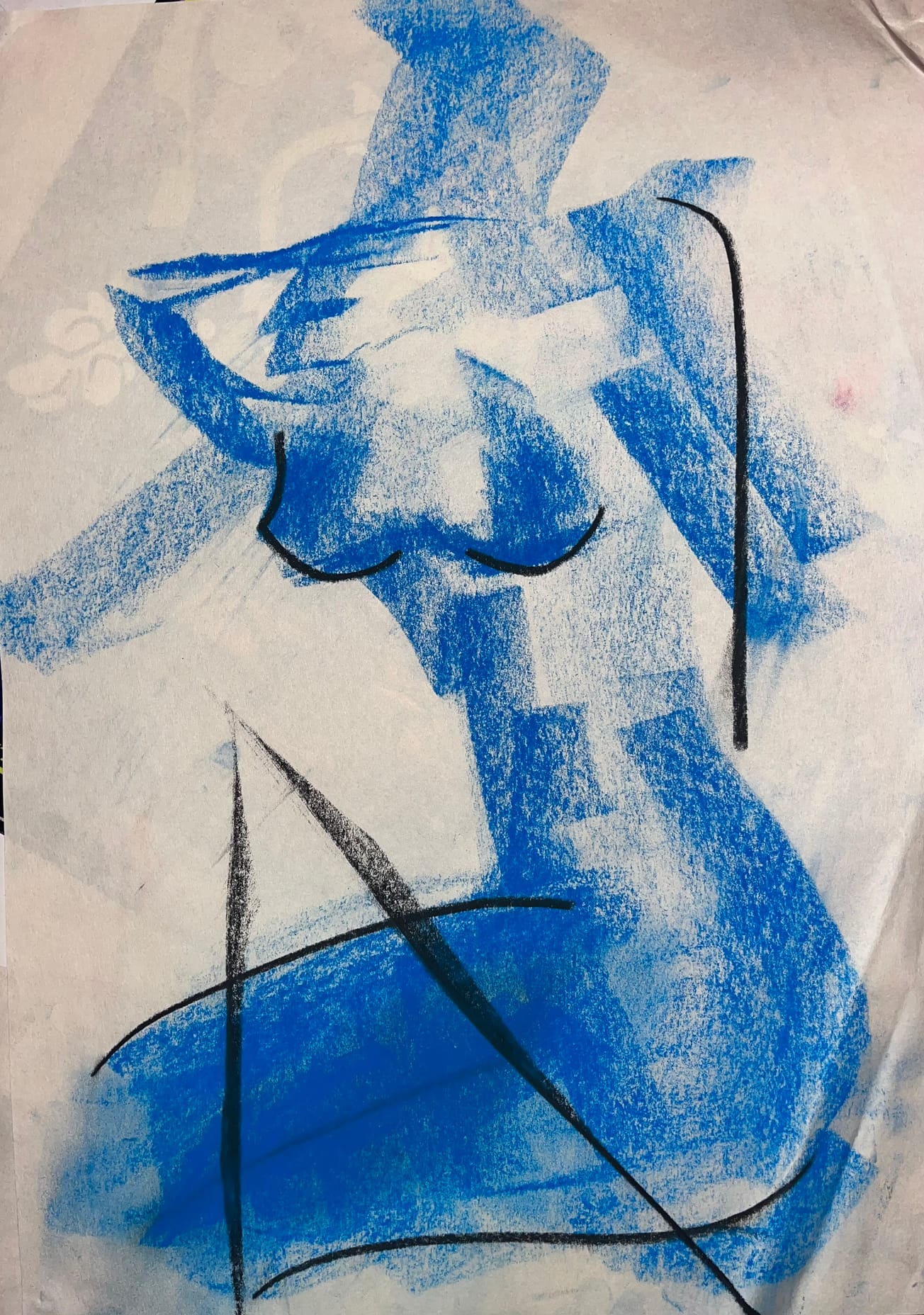

This is not to say that microaggressions and the cult of fast fashion aren’t profoundly affecting our world but rather, we can’t sustainably surround ourselves with self-proclaimed mental health professionals and maddening discourse. I have realized retrospectively that social media reduced me to two eyes and a finger. I couldn’t even control what I was going to see next. In stark contrast, naturalist understanding encouraged me to use my whole body.

My immersion into this new world of environmentalism also induced a radical forgiveness I hadn’t been able to see, especially towards myself. Here was a world that demanded constant growth, change, and reciprocity to be sustained. This principle of reciprocity is just as important when understanding human relations. Frankly, you are delusional if you believe that you can exist entirely self-dependent. Hyper-individualistic conceptions of the self, perpetuated by social media therapists (think: ‘if they don’t serve you, cut them out’) have popularised this sentiment. But, through this naturalist lens, the importance of community is made all the more evident.

Through the gloom of growing up, comes a sort of elusive clarity that continues to reconfigure as we experience more of the world. We should neither run from nor cling to these brief apparitions of focus. Our minds and identities are in constant flux. In one’s 20s, one is suddenly made aware of one’s fallibility. The first step towards growth is to rid oneself of the fallacy that there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people. We are all products of our encounters and relationships, and to lump people into such black-and-white boxes as young adults is to do a disservice to our capacity to become better. It is easier to conclude one’s imperfections are character-defining and shameful rather than a foundation for our progression. That is to say, it requires less emotional exertion to wallow in our capacity for darkness than to accept that as a part of ourselves and move on.

As a result of my immersion in nature literature and the environmentalist cause, my shift in perspective has made way for a radical forgiveness and acceptance of people’s capacity to change. To write about nature is to engage your entire self - body and spirit. And while this priority has prompted a change in myself, I will not hold onto it; there is always more to discover.

Featured image: Adam Lui

Has a piece of media ever changed your outlook on life?