By Charlie Graff, MPhil English

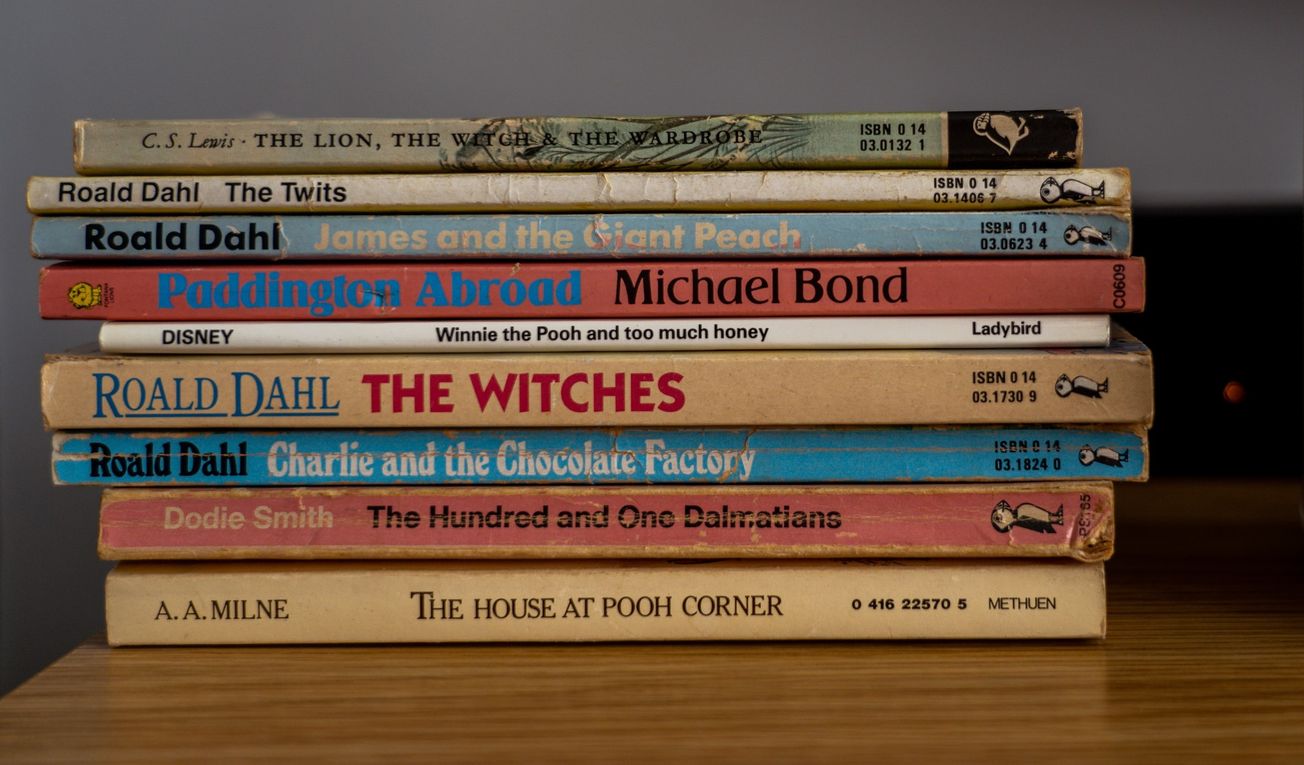

Penguin have come under fire recently for, once again, altering the texts of the notorious bigot and beloved children’s author Roald Dahl to conform to what the Telegraph has been calling ‘the hair-trigger sensitivities of children’s publishing’. Responding to the criticisms, Penguin have announced that they will be publishing a new Roald Dahl Classic Collection alongside the revised versions, aiming to both quell and profit off of the national outrage the revisions have sparked.

The arguments which have been brought against Penguin can be categorised into two types; (a.) we should not censor books which come from a different era, or we will rob ourselves of valuable historical documents and be left with an inaccurate view of a sanitised past; and (b.) we should not censor Roald Dahl’s books, as he was an excellent writer with a classic, distinctive style that we risk losing by repeatedly revising his texts.

These two arguments, (a.), the historical argument and (b.), the aesthetic argument, appear at first to be both rational and unrelated; we would instinctively apply either argument to any publisher seen to be going back and editing beloved cultural treasures, whether in the name of ‘wokeness’, as right-wing commentators allege, or otherwise. In the case of Dahl, however, we begin to see the common-sensical notions of historical accuracy and distinctive style breaking down, revealing a common root: authenticity.

First, there are no ‘original’ Roald Dahl texts, beloved by all, which are being altered out of their distinctiveness: every decade for half a century Dahl has had to be sanitised since, even for his own time, his views were exceptionally bigoted and he was not afraid to print them.

In 1983, he wrote an article for the New Statesman where he said, ‘There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity,’ going further to add that ‘there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on [Jews] for no reason.’

1983 was a long time ago, though just as close to our time as to Hitler’s. Even the Telegraph is willing to admit that ‘[f]ew would defend retaining the “n-word” in contemporary publishing, or any number of other outdated racial slurs which bring the modern reader up short and do not add to the text.’

What this reveals is that the aesthetic argument for not changing Dahl is not premised on what he actually wrote or intended to write, but a version of him produced by revisions of the texts. In the aesthetic argument, the ‘authentic’ or ‘classic’ Dahl is not the same as the original Dahl.

As such, the historical argument contradicts the aesthetic argument. If, in the name of the aesthetic argument, one maintains that a certain degree of sanitisation is permissible, since the ‘authentic’ Dahl we lament losing is the one with the racism toned down a tad, then there can be no argument that we risk losing an authentic historical document by altering Dahl’s texts.

The historical documents are the uncensored originals, which are already nowhere purchasable from mainstream book retailers and haven’t been so for fifty years. It would be very surprising if the planned Roald Dahl Classic Collection does anything to change that; Penguin have said only that it ‘will be based on the texts that were published prior to the recent revisions’, which is suitably vague.

Though many outlets have begun to praise Penguin’s decision to release the ‘originals’, the publisher has made no mention anywhere at all of releasing original texts, only ‘classic’ ones.

Paradoxically, however, the aesthetic argument also relies on the premises of the historical argument, contradicting itself; if Dahl’s distinctive style is under threat of erosion by repeated revisions of his texts, then surely it is only the original publications of his texts which represent his style authentically.

To refer to revisions of the texts as authentically Dahl’s, despite the fact that they already contain changes that Dahl did not write or intend, implies that acts of revision, or ‘censorship’ as pundits would like to term it, do not necessarily affect the authenticity of the texts in any meaningful way.

To resolve this aporia, conservative pundits have suggested that there is a happy mid-ground between revision and conservation of Dahl’s texts. They claim that the most recent revisions exceed this happy mid-ground by changing too much. So, forget the historical argument, pundits are willing to agree that Dahl’s originals are unfit for publication and should be ‘censored’ to some degree.

This makes the ‘censorship’ question quantitative rather than qualitative, as if ‘newspeak’ was permissible for them in small doses. Of course the historical argument relies on the idea of an uncensored text serving as an historical document. A lightly censored text would not serve this purpose. But since the notion of a ‘happy mid-ground’ of revision contradicts the historical argument, it also contradicts the aesthetic argument which is secretly premised on the former: if some degree of revision does not affect the authenticity of the text, what degree of revision does?

What is more significant: The 1973 revision that turned the Oompa-Loompas from pygmy slaves kidnapped from ‘the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had been before’ into the orange folks fans of Dahl’s work know and love; Or the 2023 revision that made Augustus gloop ‘enormous’ rather than ‘fat’?

Is Tim Burton’s 2005 re-revision of the Oompa-Loompas back to being pygmy slaves a step towards a more authentic rendition of Dahl? Or is the authentic Dahl better captured by Mel Stuart’s 1971 version with singing, little orange people, a version which predates and was copied by Dahl’s 1973 revision?

Is Dahl’s distinctive style even the product of his own hand, or is it the product of the many revisers, the myriad, nameless Oompa-Loompas, charged with making his work palatable for children?

What we begin to see is that, without the historical concept of authenticity as ‘what the author wrote’, the aesthetic concept of authenticity as ‘the writer’s distinctive style’ is neither here nor there.

The ‘authentic’ Dahl of the aesthetic argument is one more Willy-Wonka: a face to put on an industrial apparatus that no longer needs its namesake and is constantly trying to clean up the mess left by him. But if Dahl didn’t write everything he wrote, what is his distinctive style?

The Telegraph is happy to publish that the 2023 revisions ‘mute the original sense’ of the revisions they are revisions of. Would they say the same of the 1973 revision?

Apparently they are too ‘woke’ for this essential step. If censorship is wrong because it erases the original meaning of the text, why is the Telegraph only calling for Penguin to reinstate revisions made as recently as 2001, 11 years after Dahl’s death? Surely we should liberate Dahl’s originals, with all of their misogyny, racism, classism, ableism, fatphobia, etc. uncensored.

To quote Brian Cox, anything less would be, ‘a kind of form of McCarthyism, this woke culture, which is absolutely wanting to reinterpret everything and redesign and say, ‘Oh, that didn’t exist.’ Well, it did exist. We have to acknowledge our history.’ Perhaps Salman Rushdie is quite correct in calling these new changes ‘absurd censorship’.

I would argue that conservative pundits and ‘free speech’ advocates, as they call themselves, are still far too ‘woke’ according to their own premises; they have not gone far enough in defending the preservation of Dahl’s works.

The Daily Mail has printed that Penguin ‘must still go further, and cancel the new censored versions completely.’ I believe that the Daily Mail - indeed all of Murdoch’s outlets - must still go further and join me in calling for Penguin to immediately stop printing any revised editions of Dahl’s work.

Dahl should be printed as he intended himself to be read, in his distinctive style. And since the pundits insist that Dahl’s works should serve as important historical documents, I believe that these originals should be no longer filed under ‘Children’s Fiction’, where they would be highly inappropriate, but in their proper place in the ‘History’ section, near other fictions of historical importance, such as the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ or ‘Mein Kampf’

Featured Image: Courtesy of Unsplash, Nick Fewings

What's your opinion on the censorship of Roald Dahl's works?