By Katie Chalk, Arts Deputy Editor

According to his contemporary Ben Johnson, William Shakespeare ‘was not of an age, but for all time’. Was he right?

Today marks the end of the eighth annual Shakespeare Week. It is officially a celebration for primary schools, but who says undergraduates can’t join in the fun? It’s a great opportunity to ask: is Shakespearean theatre as relevant, accessible and worth studying now as when you could buy a ticket for the same as a loaf of bread?

Conversations with students revealed the positive practical implications of studying him. Kate Bowie (Second Year, English) said: ‘I’m all for expanding the canon but so much literature is intertextual that you can’t access later works without a grounding in Shakespeare.’

Considering this, it makes sense that Shakespeare is compulsory at GCSE, A Level, and in many English Literature and Theatre degrees at British universities.

At Bristol, however, the course structure of the English and Theatre and Performance degrees means students can feasibly avoid dedicating more than a few weeks to Shakespeare during their degree. So what’s being achieved by making him optional?

For some, it is exactly this perceived centrality in literature that rubs people up the wrong way. ‘The Bard’ is present everywhere. It is the insistence of his unflappable genius and cringy paternalistic imagery like he’s the ‘father of modern literature’, that is tired. By giving students the choice whether or not to study him, especially after having him shoved down their throats by the GCSE and A Level National curriculum, may help mitigate some of this resentment.

Maybe it is the fact he has been obviously adopted by the undeniably political education system as ‘essential’ that has made him the face of conformity. He’s become the cover-boy of the plethora of old white men who still dominate the academic literature canon and who obscure overlooked voices.

Students can feasibly avoid dedicating more than a few weeks to Shakespeare during their degree.

So, if he is to be studied by undergraduates, choice is important. After we accept this, maybe the issue isn’t so much whether to study him, but how.

‘Shakespeare is there to be challenged, disrupted and unravelled, rather than venerated as a ‘genius’’ insists Dr Eleanor Rycroft, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Theatre at Bristol University.

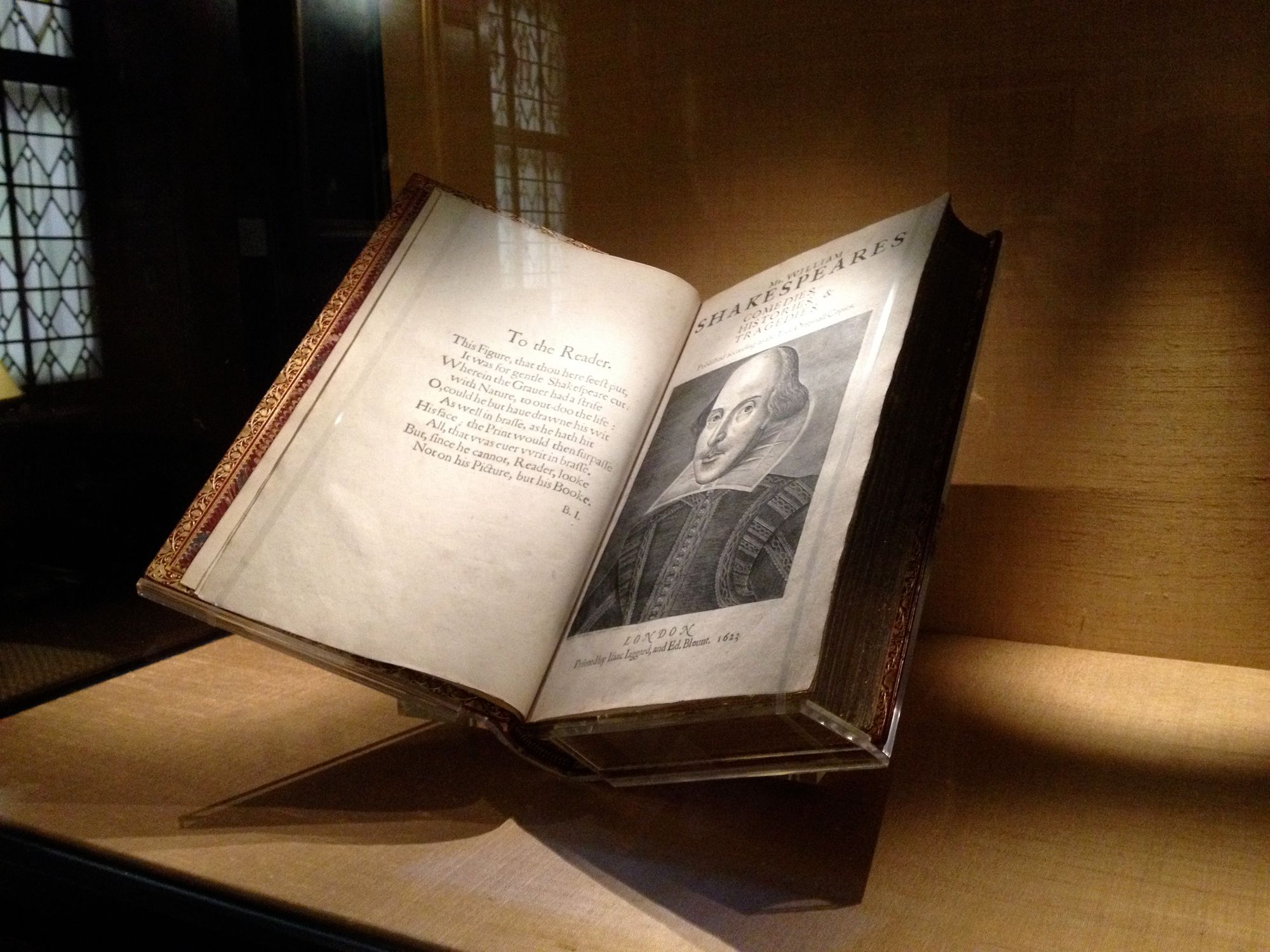

Professor of Early Modern English Literature, also at Bristol University, Matthew Steggle agrees: ‘Shakespeare is not a timeless, transcendent genius whose lessons stand for all time – that old-fashioned idea of The Bard – but rather a particularly interesting writer whose works can be understood in terms of other works from the period and beyond.’

Sure, Shakespere was a trend-setter, and it’s fun to trace his influence, but there’s a difference between that, and the weird academic cult which venerates him like a God and enshines his works as quasi-holy, immortal and fixed.

From a performance perspective, his work can, and should be played around with. Some of the invigorating revitalisation attempts of Shakespearean plays appear when creative risks are taken.

‘Cross-gender and colour-conscious casting practices open up excellent opportunities’. Dr. Rycroft notes. She recommends the RSC’s matriarchal version of The Taming of the Shrew (2019) and Clean Break Theatre company’s Donmar Trilogy (2016) in which all-female performances of Julius Caesar, Henry IV, and the Tempest are set in a women’s prison.

Maybe the issue isn’t so much whether to study him, but how

This is the kind of thing keeping students engaged now. All these productions are available for free for students via DramaOnline, which, now a theatre ticket will likely chew up a good chunk of your student loan, is a god-send for bringing the texts alive. This is, afterall, the mode by which they were supposed to be consumed, maybe this is how they should be studied too?

Dr Mark France, Lecturer in Theatre and Performance at the University of Bristol points out that arguments about the ‘authenticity and quality’ of Shakespearean verse delivery tends to ‘privilege certain types of voices and exclude others’, something which can be challenged and explored in practical study of the plays.

In this spirit, Dr France excitedly reveals his plans for a ‘Shakespeare in Performance Summer School’, aimed at international students, which currently in the works: ‘It's a three week course which takes the student on a tour from Early Modern stage practice, through the eighteenth century rise of celebrity Shakespeareans, to some of the more radical stagings we might see today...and hope to include as much of a programme of workshops, performances and experiences as the Covid-19 restrictions allow.’ There's more information on the course here.

For theatre students, this is all fabulous. But is the answer to studying Shakespere in Literature to turn book-ish English students into experimental Shakespearian performers too? Not quite. But keeping the emphasis on watching plays live or recorded, reading snippets aloud and being playful and radical with the texts are all essential components teaching Shakespere to undergraduates in a fun, relevant and accessible way.

In Defence of Poetry: my tumultuous relationship with verse

Literature through lockdown: What we can learn from reading the classics

If undergraduates are going to keep opting for Shakespeare, it has to move with the times, it is not disrespectful or risky. As Dr Rycroft enthusiastically concludes, even though the man is long dead, ‘Shakespeare will survive!’ and I have to agree.

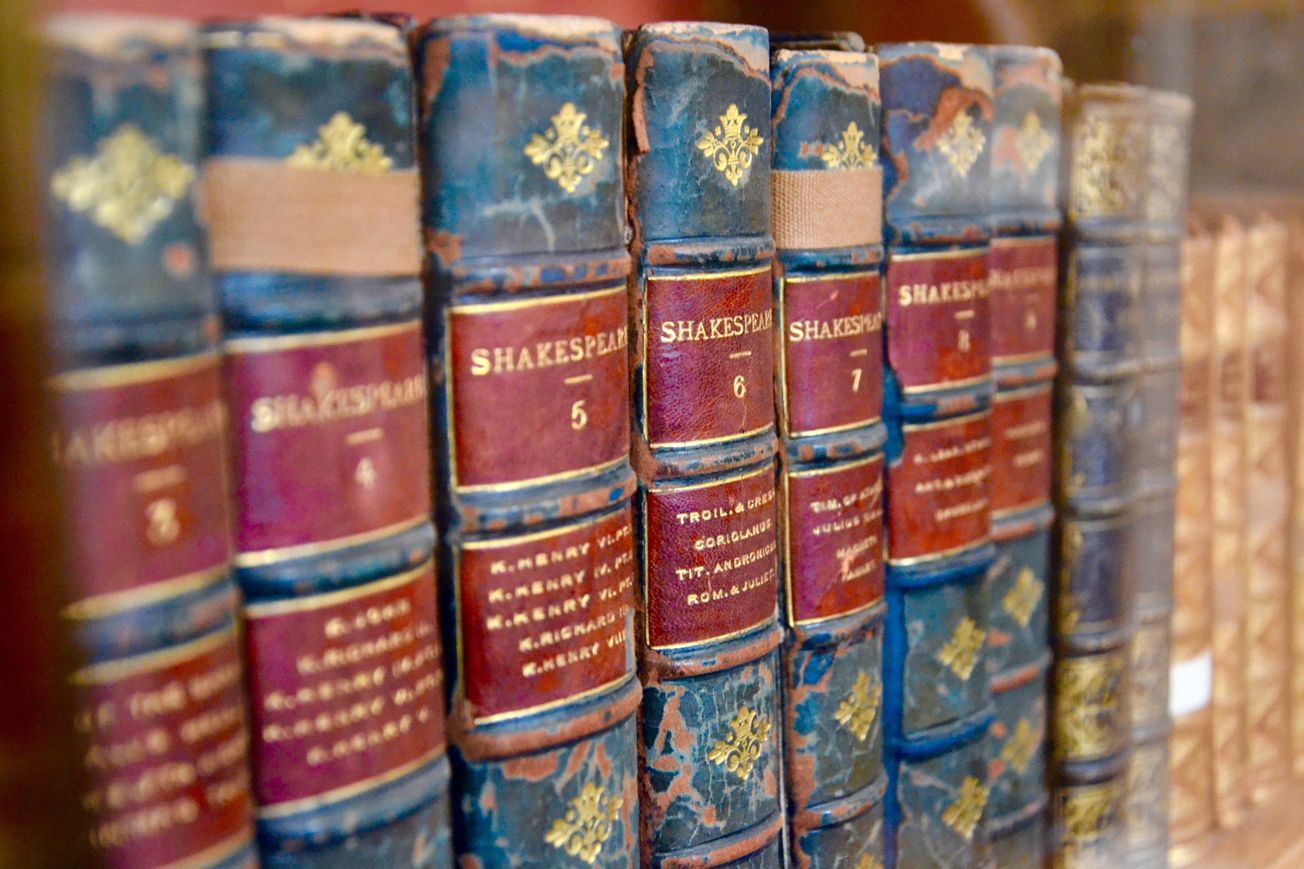

Featured Image: Flickr / Eric Schwebke

Do you enjoy Shakespeare?