By Lilia Sebouai, Second Year English

At Bristol’s very own Watershed, public intellectual, writer and historian Edson Burton introduced the two documentaries being screened at the special event for Black History Month. Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Masks and The Stuart Hall Project trace the impact of two of the foremost provocative and empowering voices in 20th-century racial discourse: Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist Frantz Fanon and New Left cultural theorist Stuart Hall.

Rich and thoughtful Introduction by @EdsonBurton for #BlackHistoryMonth double bill @wshed on Black public intellectuals Frantz Fanon / Stuart Hall by two of UK’s leading Black artist filmmakers Isaac Julien / John Akomfrah . pic.twitter.com/QN9pZRmFBZ

— Mark Cosgrove (@msc45) October 6, 2018

Twitter / @msc45

Burton crucially identified a key thread between the two theorist’s studies as the examination of the shattering effects that colonialism has on its victims and their sense of identity.

In Frantz Fanon: Black Skin White Masks, black British filmmaker Isaac Julien doesn’t adhere to traditional modes of documentaries. He instead creates a interweaving collection of interviews and archive footage coupled with an actor dramatising and embodying the journey of Fanon’s life.

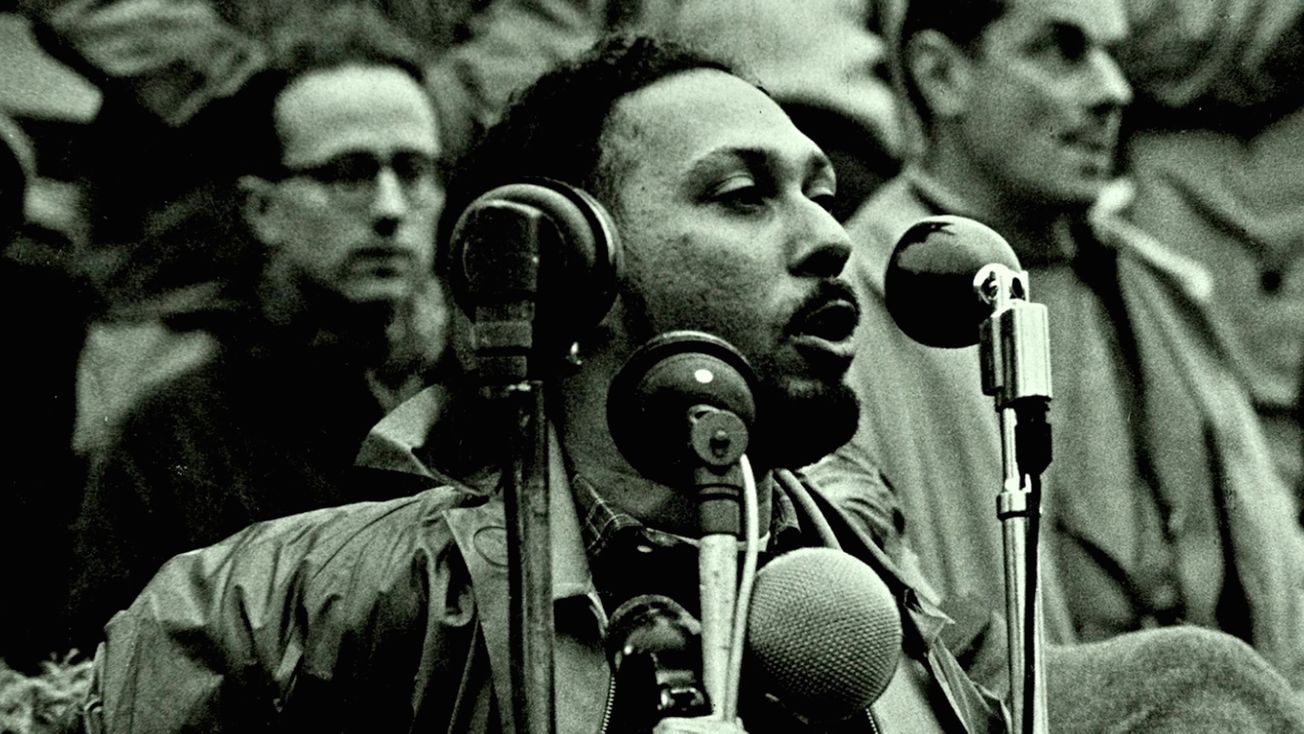

Having already featured as a narrative voice in Black Skin White Masks, John Akomfrah’s The Stuart Hall Project further illustrates the vast impact that the esteemed public intellectual Stuart Hall caused in cultural theory from the 1950s onwards. Akomfrah projects a mingling of video archive and provocative questions about identity to the soundtrack of Miles Davis, a beacon of the jazz movement and a figure who Hall said ‘matched the evolution of his own feelings.’

Watershed / Smoking Dogs Films

A major theme throughout the documentaries is the journey of the colonised to create an identity independent of their masters. Hall pinpoints the beginning and spread of globalisation as the crumbling of Empires across Europe in the wake of the post-War War, in itself marking a crucial strengthening of identities. However, once its victims were freed from the shackles of colonialism, they couldn’t simply shed their previous label of ‘other’. As in a colonial relationship, there is a complete denial of recognition towards the man of colour, as racism completely depersonalises.

Yet in Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon comments that the form of racism that cut him deepest wasn’t the way in which he was treated, but the way in which he was looked at. He recalls a meeting with one of his French female patients, when he started politely asking her questions and she screamed: ‘I don’t want this black man to touch me! Take him away!’ He says that in this moment, he felt his sense of self-image shatter, he was no longer an autonomous self and all that he could feel around him was ‘a whiteness that burn[t].’

In The Stuart Hall Project, Hall draws upon a similar story told by Fanon, in which he was walking along the streets of France when a little girl pointed at him and said: ‘Look Mamon, a Negro.’

In 1951, Hall won a scholarship to the University of Oxford. However, despite his clear intellectual capacity, Hall realised that he couldn’t ever really be a part of the English education system because racism is something that is inscribed on the skin of the subject - it is literally visualised. This created the realisation that men and women would have to rebel and break social norms in order to create a new identity for themselves, as there wasn’t one for them to simply step into.

In line with this, Fanon longed to create a freedom across society, free from racial barriers. When he arrived in Paris from Martinique, he realised that what they were missing was ‘egalité’, and equality must first be achieved before a true sense of self could be obtained. While still deeply involved with the politics of colonisation, Fanon fell in love with a white woman, Josie Fanon. Despite the racial backlash that he was forced to incur, Fanon simply stated that he was a free man and that whoever he chose as the object of his desire was nobody else’s business.

Watershed / Smoking Dogs Films

Hall also suffered similar oppression. He married Catherine Hall in 1964 and due to the whiteness of her skin, they experienced racism like never before, with Hall describing the experience as ‘traumatic’.

In the current climate of the migrant crisis, these issues that were touched upon in the 1950s are still very relevant. Frantz Fanon famously said: ‘in the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.’ This could be read as a plea against the rigid identity moulds issued by those in positions of colonial power.

However, perhaps the intrinsic mystical nature of belonging and identity means that a true sense of self can never really be defined. In a world of constant demographic upheaval, our identity is ever-changing and ever-moving, and there will always be a constant struggle to create a final sense of self.

Featured Image: Watershed / The Stuart Hall Project / Smoking Dogs Films

Will you be watching the films discussed at this special Watershed Black History Month event?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter