Flora Pick, Deputy Music Editor

For indie kids of a certain age and persuasion, Sarah Records was it. An authentically scrappy underdog, releasing small records that made big waves.

Born in a basement flat in Clifton, Bristol’s own indie label ran a bare bones operation throughout the late 80s and early 90s, releasing records that reached out into the bedrooms of a generation of misfits. Pressing music that spanned genres, their releases were tethered to a central appreciation of pop sensibility, and to the associated power of the 7" single record format.

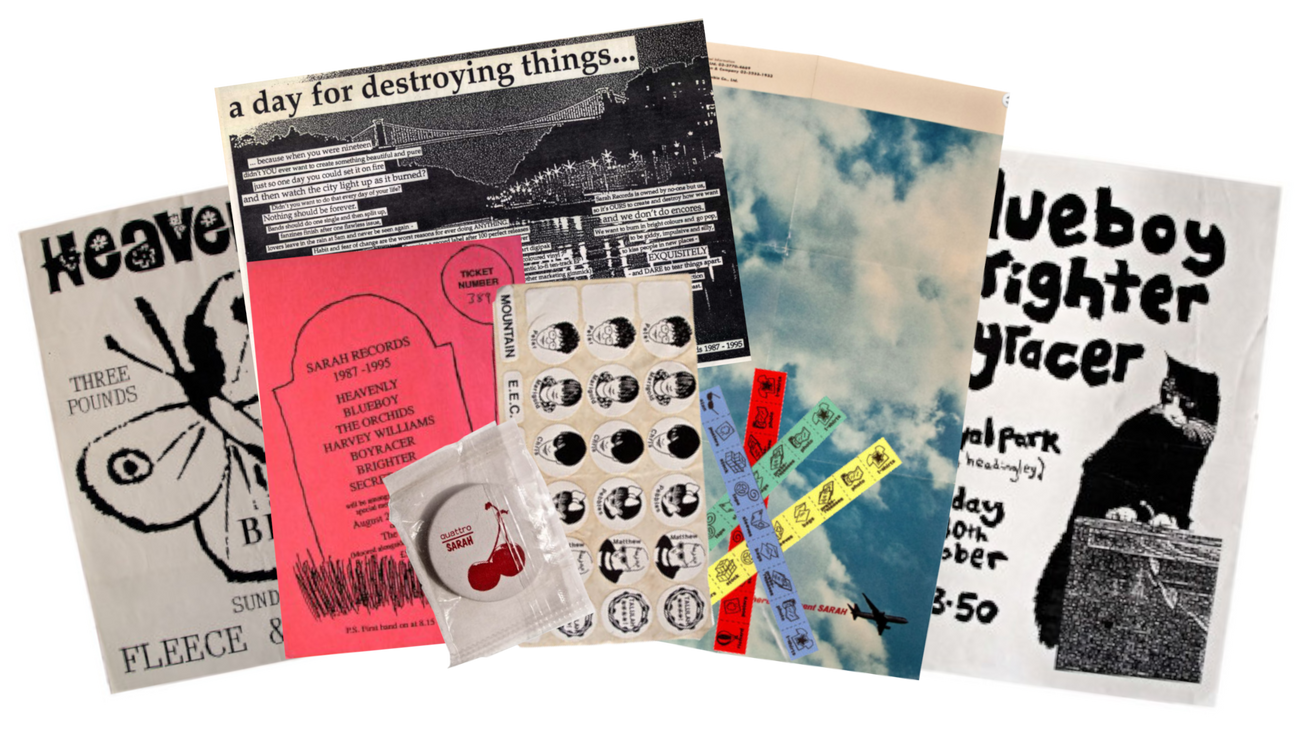

The latter tenet held true throughout their lifespan; their music was always accessible with what could be eked out from one’s student loan. Despite later media assertions of just what a ‘Sarah band’ should sound like, the label ended up home to a strikingly unpredictable array of artists, from the hazy lo-fi balladeering of Blueboy, to the blown-out, proto riot girl of Heavenly. In less than a decade the label put out over 100 official releases, with some apparent inbuilt fatalism bringing it to its close.

This was not before managing to develop a certain cult of personality that has never fully washed out from the city, in addition to establishing a legendarily bizarre antagonism with the British music press. As recently as 2014, Bristol’s own Arnolfini exhibited Between Hello and Goodbye, a retrospective exhibition accompanied by a one-off concert. How did such humble origins give way to such a legacy?

Though popular knowledge would have the label’s glory days to span 1987-1995, circumstances of their fêted end being well documented (more on that later,) the birth of Sarah Records was less a distinct act of creation than one of natural evolution. Established by Clare Wadd and Matt Haynes — the former while she was still attending Bristol Uni — Sarah emerged from, and maintained firm roots in, the pair’s mutual investment in zine culture.

Individually creators of cult indie zines Kvatch and Are You Scared to Get Happy, a shared frantic adoration of jangle pop alongside a passion for typeface swollen with exclamation marks facilitated their meeting. Talking with Clare, she described how this initial contact came about. She began writing to Matt as a teenaged, geographically isolated fanatic of his work. Prior to her moving to Bristol for university, she acted to draw herself into the epicentre of the music scenes she so admired from afar. Commenting on the state of fan culture at the time, Clare notes that:

‘Pre-internet there was a lot of lonely young people staying up late in their rooms at night, listening to John Peel.’

‘Obviously we always wanted to sell as many records as possible, but we were mainly looking for bands we loved.’

Without social media, these connections were made on paper. Ultimately, it was an instantaneous kinship between the two and a subsequent desire to share the art they loved that led to Sarah Records’ formation. The platform was never intended to turn a quick buck: ‘The premise of the label was always that we were in it to put out records by our mates, not to make money

The pair quickly found themselves exhausted by the practices employed by mainstream labels that they saw as exploitative of fans: rerelease upon rerelease, the packaging of singles in pricey 12" formats to justify inflated prices — all made their music to be less accessible to its largely student audience.

To a pair just treading financial water (though Clare was quick to point out that the label never once went broke, a point of honour for one who went on to work as an accountant), economising through their exclusive release of cheaper, 7” singles was a selfless act: ‘We wanted it to be affordable out of pocket money or uni grants, rather than to be exclusive for collectors.’

From its outset, the label was imbued with some level of adolescent fanaticism, the value of which was not underestimated as it bled into Sarah’s image. You see it reflected in Clare and Matt’s policy of replying to every letter they received; as the label drew a crowd of ‘slightly lonely, outsider people’ from across the country and beyond, this pre-internet networking ended up forming the basis of the pair’s social life.

The aesthetics of their former DIY-zine-punk sensibility collage carried over to the physical copies of their releases. For any variation that existed amongst their musical roster, there was a maintained visual continuity.

In this way, Sarah seemed something akin to a collective, singular in its direction, its image something cultivated by every artist put out under their label.

When questioned on Sarah’s heavy-handed use of Bristol’s geography to adorn their releases, Clare explained how the pair consciously positioned themselves as music industry outsiders:

‘There was that whole Oasis thing where you moved to London and you got into all the tabloids... We were setting ourselves up as against London.

‘We didn’t want to be a part of the music business, we wanted to be against the music business. We wanted to do things our way.’

Clare remarked upon a certain ‘We’re here and you’re there’ mentality – the label’s rejection of the capital was a point of honour. Sarah remained a constant devotee of Bristol, equally affectionate of its iconic landmarks and rubbish strewn side streets.

The distance from the capital meant that it was easier for the mainstream music press to make snide comments from a distance, without fear of retribution; ‘It became terribly easy for the press to slag us off, because they would never bump into us and have awkward situations - they wouldn’t know us if they did.’ ‘Twee’, as a press descriptor of the label, drew particular ire. More than a nod to the kitsch of 60s pop, Clare sensed malice in the term:

‘It seems a patronising word, with a hint of female gender about it. It was applied to men in the context of the music, but if you were to ask someone on the street (who had never heard of tween indie) what twee meant, they’d probably say a little girl with pigtails and ankle socks.’

Not as apolitical as its detractors believed, Sarah had its own simmering agenda. The very friction they were capable of inciting was surely some sign of success, even if it stung slightly.

The music was pushing against an indeterminate something, be it the chauvinism of certain NME and Melody Maker journalists, or the pretension of music that positioned itself as ‘eternal’.

While their musician’s romantic pop sensibilities could easily be read as apolitical, the supplementary texts put out with releases maintained a lefty sensibility firmly rooted in the punk zine spaces from which they grew. One of the label’s most successful exports, Heavenly, would go on to be eternally associated with the US’ riot girl scene, being distributed iconic K records in the states. Subversion was innate to the label, turning away from the nepotistic feedback loop of the capital, even if it seemed unobvious at the time.

Listening to Sarah’s releases, it’s easy to begin drawing lines between what the label put out and more contemporary bedroom pop — its minimalism provided a bare bones vitality to music, supplying just what was needed - economy rather than laziness. This isn’t to say it isn’t pretty. With jangly guitars sound tracking the woes of isolated enthusiasts, Sarah made people enamoured. Fans of recent jangle pop darlings Alvvays are likely to identify something they like here:

The cycling of clean guitar and harmonised, layered vocals conjure a nostalgia for something you’re not sure you’ve experienced at all.

Evidently, some journalists felt likewise; when Venue Magazine reviewed the first Heavenly single (Sarah #30), it was described as another Sarah band with another girl singer’ - it was the label’s first release with a female vocalist. ‘For a while every review said, this doesn’t sound like your typical Sarah band!’

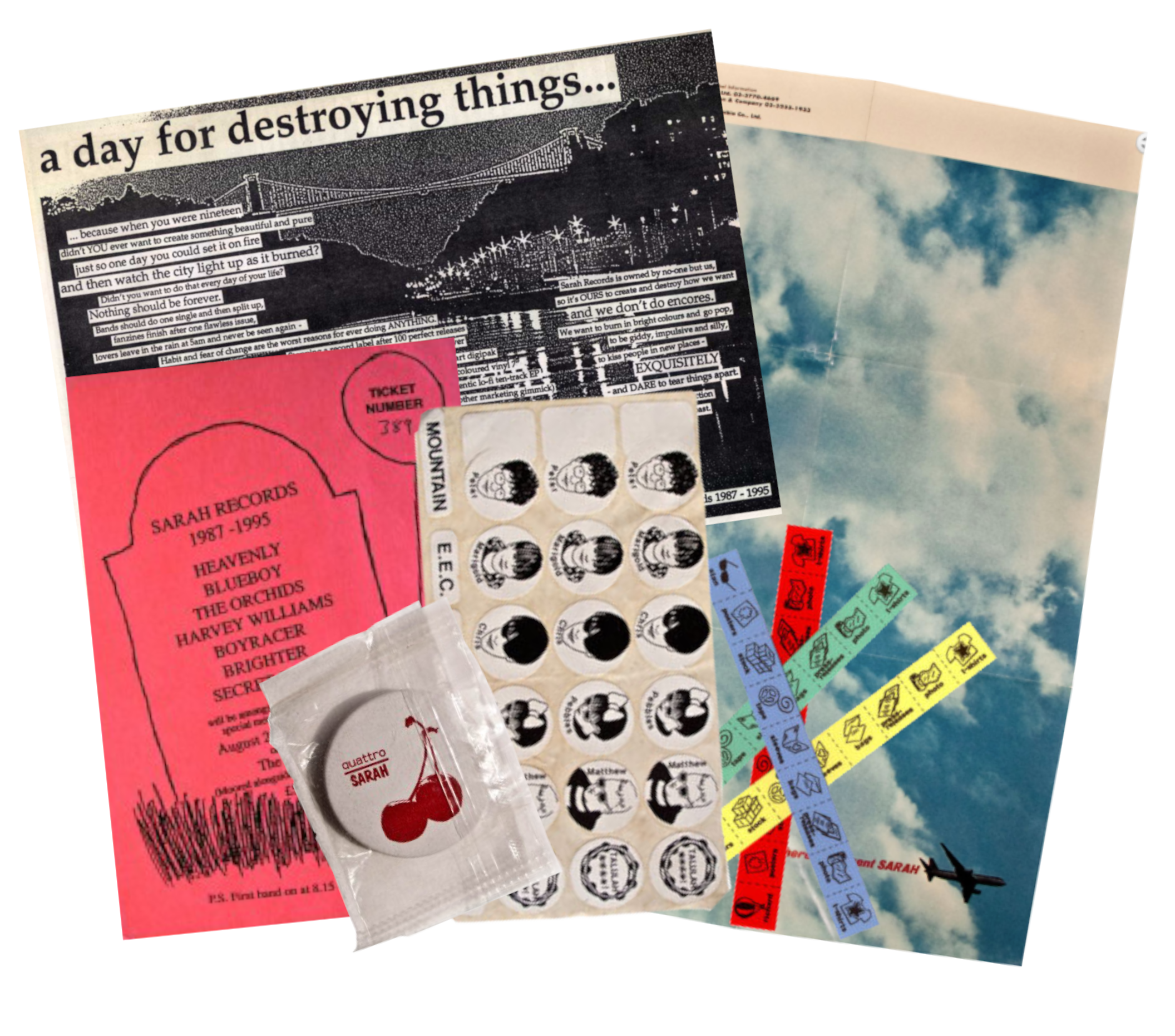

A Day For Destroying Things was a theatrical bow-out — the label commissioned half page ads in both NME and Melody Maker, announcing it’s closure with a certain flair for the dramatic. Ending on their 100th release exactly, the advert featured a series of maxims calling back to youth and ambition, paired with the iconic silhouette of the Clifton Suspension Bridge. There was a distinct sense of two people willfully constructing a legendary narrative.

Asking Clare just how intentioned they were in reality, she replied that ‘It’s easy to reinvent history and say that we’d always meant to release a certain number of singles, that it was predetermined - of course, it wasn’t at all. In reality, we put out a record that we thought was brilliant, other people thought it was brilliant, then we felt the need to put out another, then another one.’

The absence of an awkward fade into obscurity has surely stoked Sarah’s cult following; even if they didn’t set out to craft a certain mythology, the intoxicating impression of one remains. Such a sense is evident in the website, an immense archival project which puts Wikipedia page to shame. It’s all there: from the bombast of zine scans to the minutiae of magazine adverts; vague memories of adolescence are preserved for reflection and for future fans to find.

Sarah Records can be found on twitter @Sarah_Records.