By Mia Vines Booth, Second Year History

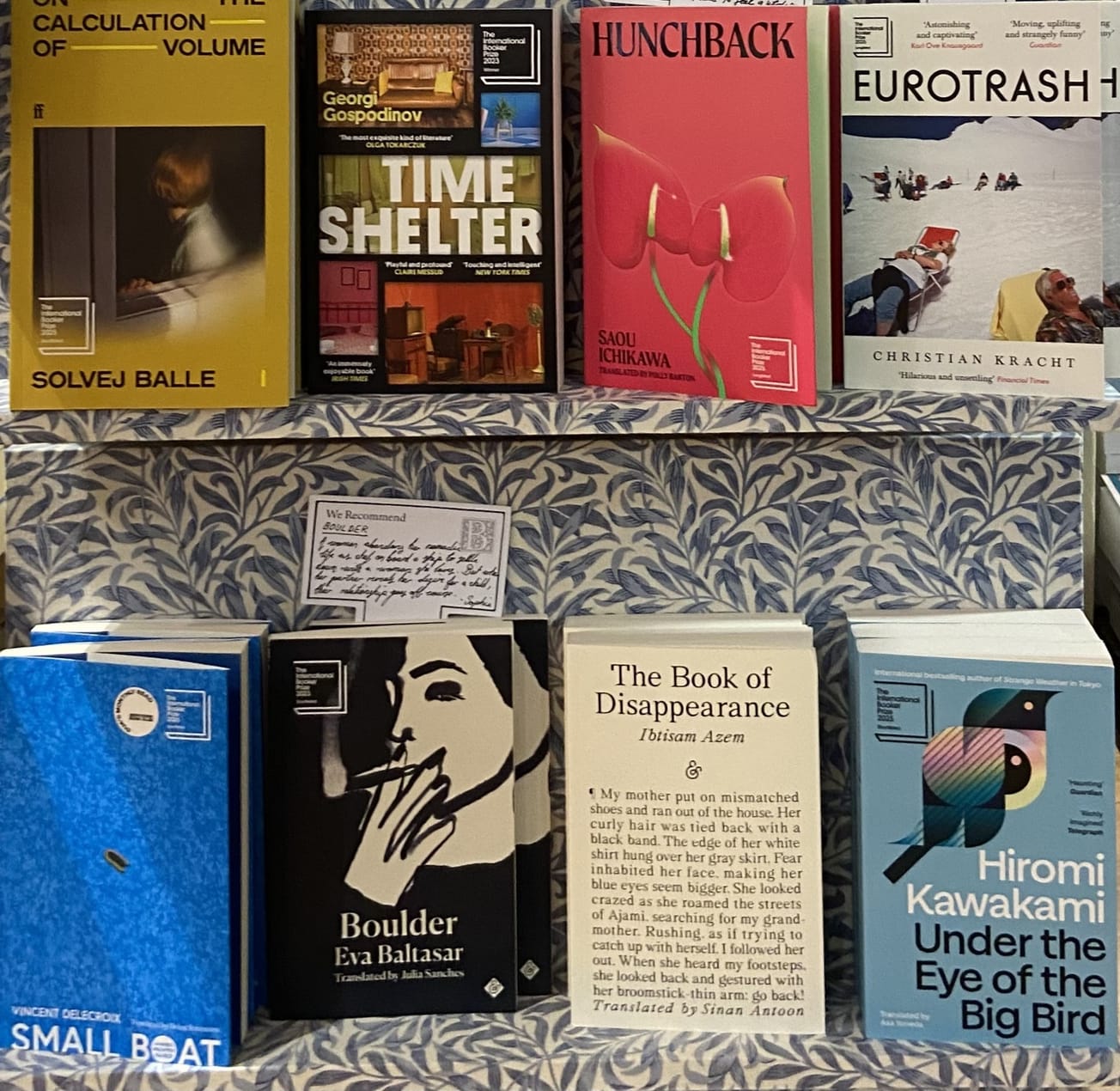

Centring on the material objects that make up feminisms, gender and resistance, Still I Rise is an impressive archival feat that blurs the lines between a museum show and a gallery exhibition.

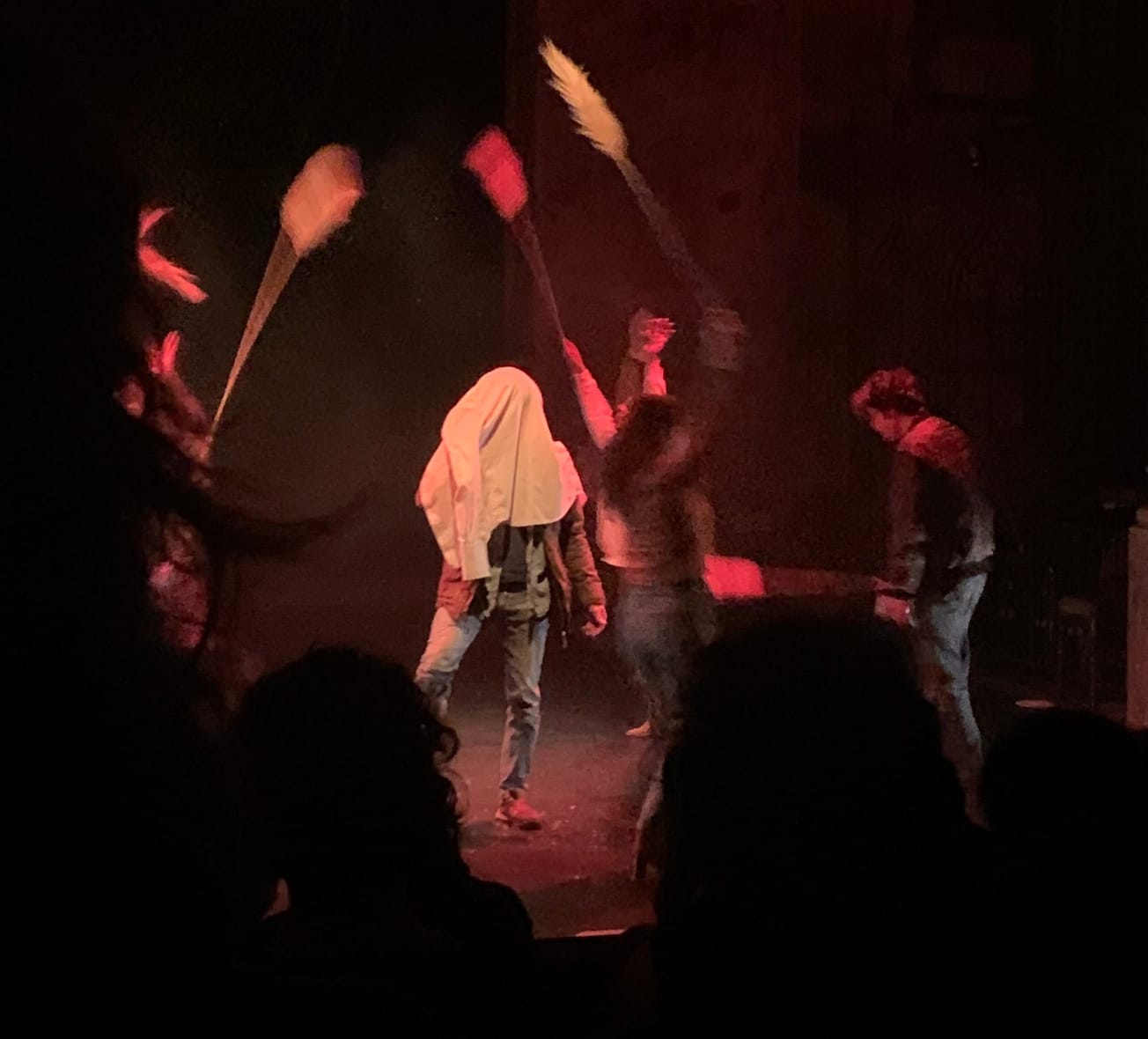

Arnolfini’s exhibition space has been transformed into a treasure trove of multimedia that confronts the history, and present-day experience, of feminisms, gender and resistance. The exhibition spans over a century – from the flags of the budding Suffragette movements, to the modern debates surrounding alternative forms of living from a gendered perspective. Crossing international waters, and deconstructing narratives between the private and public sphere, the exhibition is an ambitious journey through the subtleties and wildly varying components that make up a hugely diverse and ongoing subject matter that is still being understood and challenged as we speak. From the ongoing protests in Argentina over abortion laws and violence against women, to the global Women’s Strike initiated in the US, to the political issues surrounding the funding of Planned Parenthood, all are explored in relation to the continued patriarchal and political oppressions permeating global networks.

An expansive visual spectrum is held up to the audience – films, protest posters, photography, letters, newspapers, AIDS awareness campaigns, audio clips, architectural plans, writings from the public, sculptures and an array of multimedia artwork. The curators haven’t missed a beat, with over 100 exhibits from around 70 figures including writers, designers, artists, activists, architects and organisers.

The exhibition’s residency in Bristol touches on the city’s legacy in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, focusing on black feminist artwork and activism. Similarly, the exhibition has sourced material from the Feminist Archives South (FAS), which houses national and international material relating to the history of feminism from 1960-2000 and is based at the University of Bristol. FAS is said to be the UK’s first archive of feminist writing, publications and donated material. Nevertheless, a stronger focus on localised black feminist artwork would have brought this exhibition closer to home and impacted a wider audience in Bristol. The legacies of Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade as well as ongoing feminist organisations and events in Bristol would have connected the international with the local. Whilst Arnolfini remains a ‘creative space’ rather than distinctly a gallery, its focus on archival material at times diminished the value of the artwork in contributing to ideas of feminisms, gender and resistance.

This is a good exhibition at the Arnolfini: Still I Rise: feminisms, gender resistance. Love this in particular. pic.twitter.com/sohIQioBWb

— Sianzica Fletcher (@Sianz) November 9, 2019

Four works were of particular relevance that I will mention here. First was a filmed round-table discussion, in which individuals and representatives of institutional bodies discussed the narrative of rape culture in America and the ways in which they have been contributing to the positive wave of dismantling these narratives. Amongst women representing organisations working with sexual assault victims, journalists, film makers, and charity workers, sat a disgruntled police officer whose positioning seemed rather inauspicious next to these passionate contributors to a well-informed, nuanced and necessary debate.

The second work was a board game which satirised the double standards of middle class feminists in the 1950s. Taking inspiration from the classic children’s game, Snakes and Ladders, the board game told the story of the trials and tribulations of a working-class women attempting to support the women’s movement whilst juggling the hardships of being, well, a working-class woman. One particular square involved a conversation between middle class feminists complaining of having to go to boarding school, to which the working-class women thought to herself how nice it would be to own a pony and gain a good education. Another satirised the dinner party culture in which middle and upper-class women would complain of the woes of sexism. On explaining to these women a number of hardships that she experienced as a working-class woman, these ladies thanked her for ruining their civilised dinner party with her foul mouthed dose of reality.

The third work was a plan for Hull House, a settlement housing project created in Chicago in the 1880s by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr to house and look after the poor in deprived urban areas. This included education, arts programs, community living, sports activities, and a sharing of knowledge between different classes. Revolutionary for its age, the settlement reinforced the idea of communal living and the fluidity of classes, challenging ideas of inherent segregation that permeated divided American society in this period. So threatening was Addams and Starr’s community to the establishment that, in the 1920s, the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, named Addams ‘the most dangerous woman in America’ for engaging in the Women’s Liberation Movement to secure votes and peace for women.

Arnolfini is open! The new exhibition, Still I Rise, opens tomorrow at 11am and will be on until 15/12. Don't forget to pick up your exhibition catalogue in the Bookshop or on our online store for just £20!#stillirise #arnolfini #arnolfinibookshop #feminism #gender #resistance pic.twitter.com/rXDYqTucZj

— ArnolfiniBookshop (@ArnolfiniShop) September 13, 2019

Finally, a 1993 film by the journalist and editor Glenn Belberio entitled Glennda and Camille Do Downtown was included in this show. Glenn Belberio appears as the drag queen, Glennda, and the American feminist academic and social critic, Cammile Paglia, appears as herself. Together they engaged in a political and cultural critique that Paglia termed ‘drag queen feminism’ – in the film she also confronts a group of women protesting against pornography, calling them 'wimps' for failing to stand up to her.

All four of these examples speak to the diverse range of material included, in regard to the periods covered, the range of gendered perspectives and the nuances in this debate that Arnolfini has so successfully brought to light.

Still I Rise: Feminisms, Gender and Resistance Act 3 is curated by Irene Aristizábal, Rosie Cooper and Cédric Fauq with Kieran Swann, the Head of Programme at the Arnolfini heading Act 3, it is on until the 15th December.

★★★★

Featured image: Arnolfini

Will you be heading over to the Arnolfini soon?