By Grace Bourne, Third year French and History

In writing this article, I tried to reflect on when my understanding of rape and sexual assault was first formed. I cannot remember being given a definition, but at some point, in my early teens I had clearly established a particular, and very black and white, understanding; I needed to be wary of scary looking men in the streets but everyone else and everywhere else was safe. The Crown Prosecution Service’s 2024 survey shows that 38.2% of rape victims were ‘victimised in their own homes’, and according to the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN) 60% of all rapes are committed by someone previously known to the victim.

In my later teenage years, I entered into a relationship with a young man the year above me at school. This was my first relationship, and I trusted him to teach me what that should be like. I was completely unaware as to what constituted consent within a relationship, and I was told repeatedly by him that what he did was normal. I was forced to come to a warped understanding that entering into a relationship stripped me of my right to consent.

It wasn’t until we broke up, three months later, I sat in a PSHE lesson on sex and relationships in sixth form. I sat bewildered at the back of the room as the teacher started to list everything that I had been through. As if I’d just been punched in the gut, the stark realisation hit that what had happened was not normal. I now knew that my right to consent had been repeatedly abused. Completely overwhelmed, I felt anger, first at him and then at myself for not realising sooner what had happened. I felt stupid and thought it was my fault for staying in the relationship, that I had no right to report his behaviour because I had allowed it to happen, it was me who hadn’t understood that consent within a relationship was equal to consent anywhere else. The pain in the following months was all consuming, I didn’t know who to tell or how to explain what had happened. The lack of education surrounding sexual assault became in itself dangerous because it stopped me from feeling able to report what had happened and made me feel as if I was somehow at fault, or that my experience was invalid because it happened within the confines of a relationship, with someone I knew

Despite 60% of all rapes being perpetrated by someone known to the victim, 21% (according to RAINN) being committed by intimate partners, the CPS 2024 survey revealed that only 42% of 18–24-year-olds surveyed recognised that ‘being in a relationship or marriage does not mean consent can be assumed.’ What terrified me most about this statistic, is that among the surveyed over 65s, 87% recognised that being in a relationship does not mean consent can be assumed. The regression as a society in our understanding of rape and sexual assault is a terrifying prospect.

The scale shown in these statistics surrounding misconception around rape is disturbing and are part of why so many people are subject to sexual violence without feeling able to report their perpetrator. However, speaking to the University of Bristol’s Women’s Officer, a position only created this academic year, gave me huge hope. Aimee Massara spoke to me in depth about existing problems surrounding education around rape and sexual assault at the University, but she made sure to highlight that conversations she has been having since assuming the position have been constructive.

One of the key problems she highlighted was a vast lack of awareness among the student body that any resources surrounding consent training existed. Effective from the 1st of August 2025, mandatory consent training was introduced for all students at registration but having spoken to a dozen students over the course of my research, none of them can remember doing it. Aimee shared a statistic from a consent training module on Blackboard where only 2.5% of the student body have completed. It is therefore somewhat unsurprising that there is still widespread misunderstanding surrounding sexual assault and consent.

Education on night time safety is crucial but understanding that it is not limited to the streets is just as important. According to an article published in 2024, the correlation between alcohol and sexual assault is particularly pronounced in University settings where ‘70% of sexual assaults involve alcohol.’ Nights out, with friends or societies are a cornerstone for many of student life and this statistic emphasises the potential dangers which without proper and extensive education on consent, as well as effective reporting mechanisms, are left unaffected. One of Aimee’s ambitions for this year is further ‘collaboration with well trusted and specialised’ third-party organisations such as the Somerset and Avon Rape and Sexual Abuse Support (SARSAS) in order to ‘streamline resources and make them more accessible’ as well as help create a ‘wider community of support.’

Aimee stated ‘Mandatory consent training for all society committee members has to be improved’ because it is ‘just not good enough.’

My experience in my later teenage years is an example of how transformative, and critical, effective education on sex, relationships, rape and sexual assault can be. The importance of educating people about rape and sexual assault becomes increasingly acute as we enter an era beginning to be defined by an increase in misogyny and disturbing attitudes, especially online, surrounding sexual violence. Effective education is one of the most powerful tools in fighting the tide of growing misconception around rape and sexual assault in younger generations which puts victims in danger. Understanding night time safety is crucial but understanding that sexual harassment and assault is not limited to the streets, is not limited to strangers, is vital in protecting people, in ensuring they feel able to report assault when it happens in the street, at university, among their friends or in their own home

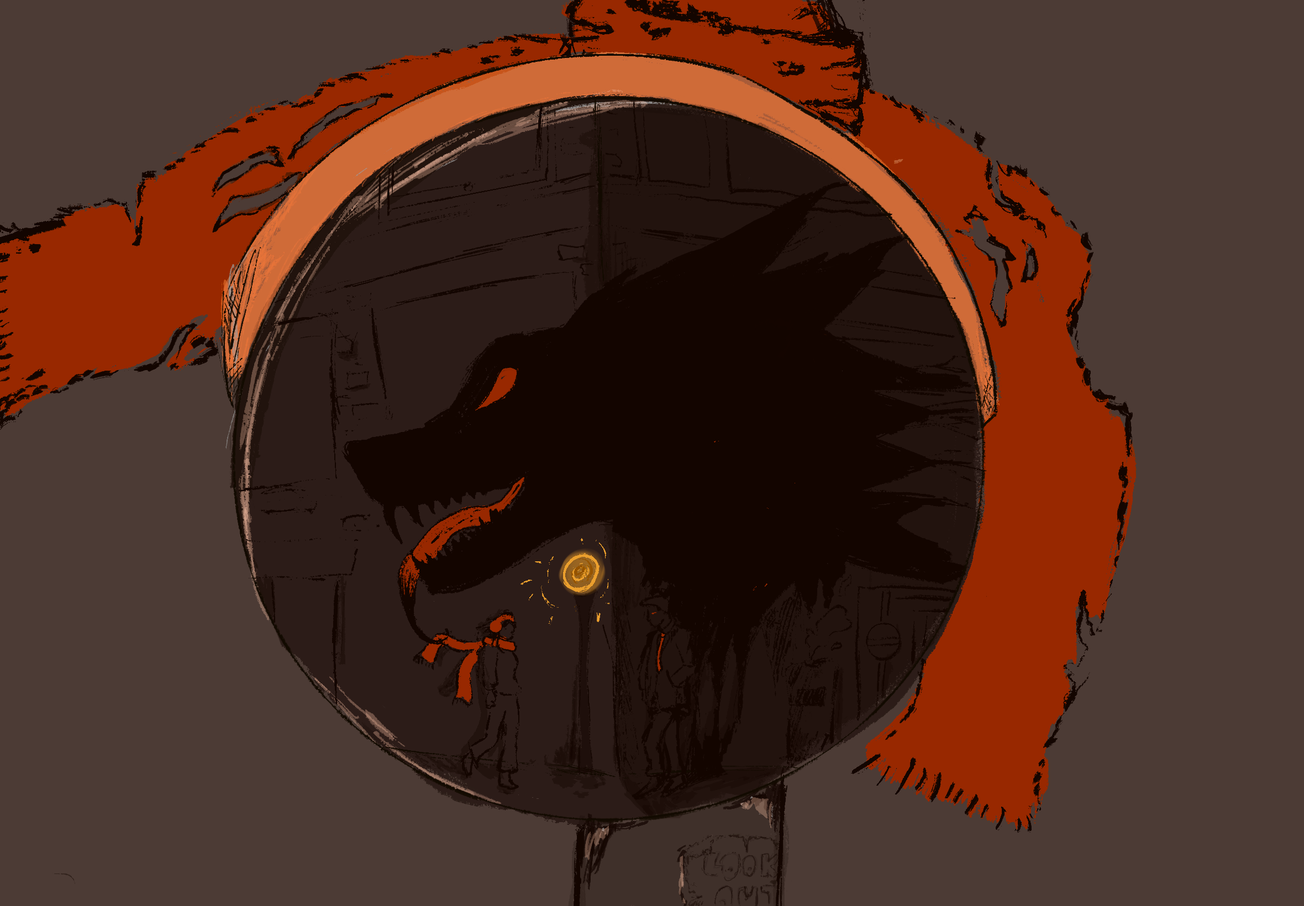

Featured Image: Simren Jhalli