By Milan Perera, Arts critic columnist

As inhabitants of the 21st century where our lives move at a breakneck pace, largely due to the dizzying heights we achieved in science and technology, we would be forgiven to think that stress is a by-product of our time. But the fact remains that since the dawn of humanity we have been tagged, stymied and propelled by stress in various shapes and forms.

According to the great historian Arnold Toynbee, the rise and fall of civilisations could be understood in terms of external pressures individuals faced at specific points in history and the way they responded. This law, which he coined ‘Challenge and Response’, galvanised warring Greek city states to front a response which could defeat the mighty Persian armies. The energies that were released during this response elevated Greeks to unprecedented heights in science, philosophy, drama and mathematics. A similar response was mustered by the English when they were threatened with the fearful Armada. The response of the English laid the foundation for a renewed self-identity and national pride.

One might ask what stress has got to do with the Greeks or the English. It is a manifestation that stress has been an integral part of our existence since the days of hunter gatherer societies. But, recently words such as ‘cortisol’, ‘serotonin’ and ‘dopamine’ have been swirling the airwaves as we appear to have a better grasp of the science behind what is loosely referred to as ‘stress’.

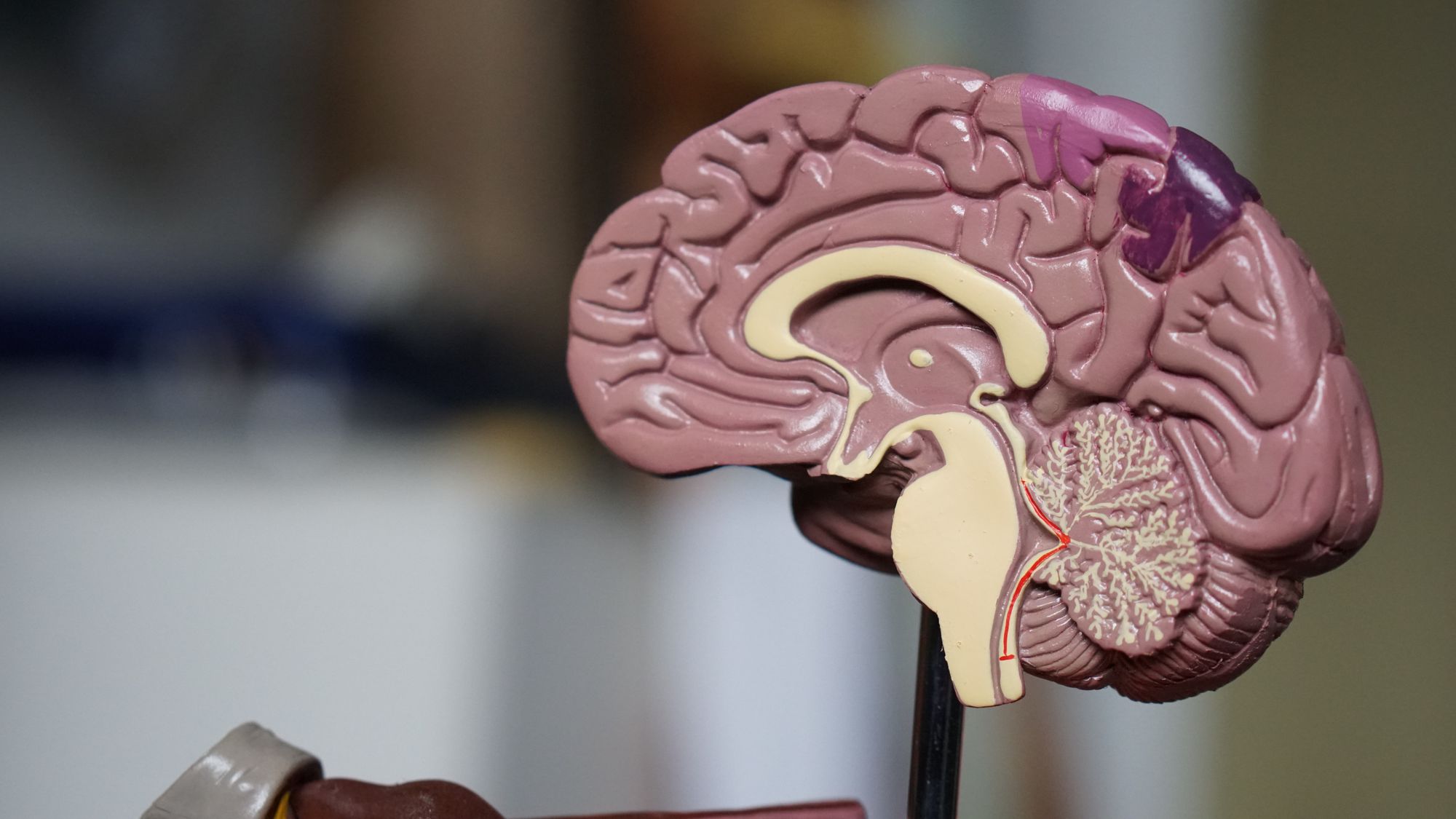

When we are startled or frightened, the ‘fear centre’ of the brain, called the amygdala, activates our central stress response system. This is known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenalcortical (HPA) axis because it comprises the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and the adrenal cortex.

The stress response system regulates hormones, particularly the stress hormone cortisol by rapidly increasing glucose levels, speeding the heart rate, and increasing blood flow to the muscles in our arms and legs; this enables us to respond to a stressor. After the danger has passed, the system works to return hormone levels to normal.

What happens when someone is suffering from chronic stress raises a series of red flags such as digestive distress, weakened immune system and change of sleep patterns. As a result of the weakened immune system, one is susceptible to viral and bacterial infections easily that could take much longer to recover than someone with an optimum level of stress.

When Epigram spoke to a consultant psychiatrist who comes across patients, especially students, who suffer from stress and anxiety regularly, they pointed out that: ‘A certain amount of stress in your life can be a constructive driving force for personal development but when the stress levels reach a chronic threshold it could become a precursor to anxiety and further down the line, depression. It is important to identify it first and acknowledge it.’

According to the science writer Arash Emamzadeh who maintains a psychology blog, managing stress requires learning about factors that influence the stress response, and then identifying and altering modifiable influences on stress, such as unhealthy thinking patterns (e.g., rumination, worry) and dysfunctional communication patterns (e.g., trolling and threats). As for reducing stress reactivity more directly, one possibility is to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (e.g., using breathing techniques) to counterbalance the effect of the sympathetic nervous system.

More than ever before employers have invested time and resources into the wellbeing of their employees, as it benefits the employers in the long run with the increased productivity of the workforce. What was dismissed as ‘cool’ and ‘fads’ a few years back have now become mainstream methods of helping employees and the general public to tackle unhealthy levels of stress in their lives.

One such practice is mindfulness meditation whose ability to lower stress is widely discussed in scientific forums and research papers. According to Psychology Today magazine meditation is associated with reduced markers of stress—reduced cortisol, blood pressure, and C-reactive protein (an inflammatory marker).

Not only mindfulness meditation but also a simple adjustment to your lifestyle could have a vast impact on your stress levels: regular exercise, a healthy diet low in sugar and saturated fats, and consistent sleep patterns will vastly reduce stress reactivity as well as depressive symptoms. Stress is nothing to be avoided but a helpful and life sustaining force that needs to be kept in check.

Featured image: Unsplash / Tim Gouw