By Jack Charters, Features Editor

Debates on the memorialisation of morally complex individuals and events have resurfaced to the forefront of national discourse owing to the Black Lives Matter movement, with the ideological battleground manifested around statues and memorials.

The toppling of the infamous Colston statue in Bristol during a Black Lives Matter march created international headlines, whilst also prompting counter-protests centered around the Winston Churchill statue in Parliament Square, London and the statue of Scouts founder, Robert Baden-Powell in Poole, Bournemouth.

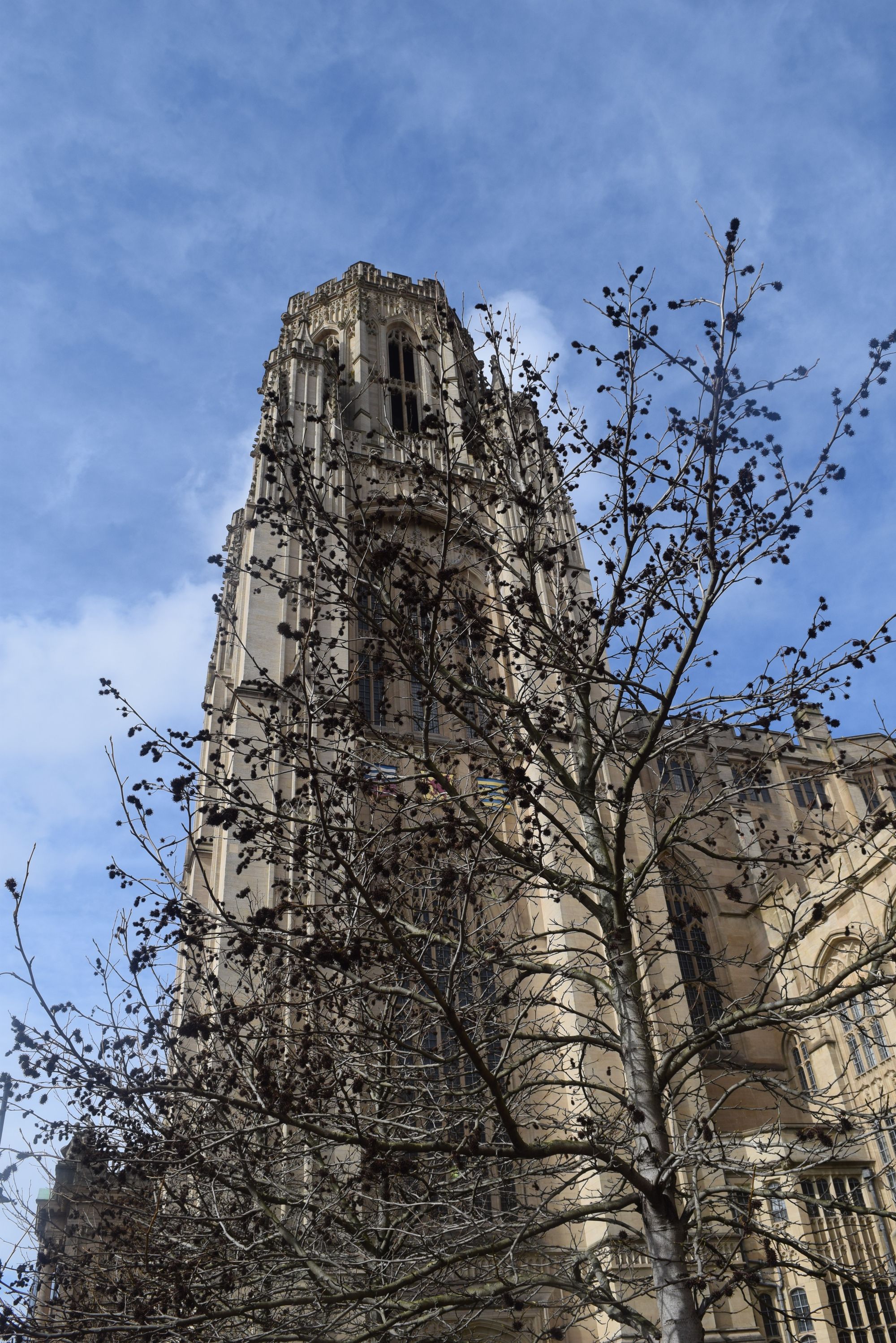

Consequently, questions have been raised about the memorialisation of contentious individuals in the UK and its universities. One such individual in the University of Bristol’s history is the namesake of Wills Hall and the Wills Memorial Building, Henry Overton Wills III.

His funding led the University to receive its royal charter in 1909 – yet the money donated was earned through his ancestors' use of slave labour to produce tobacco in the US.

It leads us to consider whether the societal function of complex objects, like the Wills Memorial building, has transcended from a glorification of these individuals to an historical artifact worth preserving? Or do they continue to contribute to a cultural narrative of racial injustice?

In 2017, three University of Bristol students challenged the role of these objects in society when they petitioned the University to rename the Wills Memorial Building. In doing so they made headlines across the country, rallying support and resistance to their cause – even sparking a counter-petition.

Estimates suggest that 85% of my university's wealth depended on the labour of enslaved people. In 2017, students petitioned the university to rename the Wills Memorial Building, named after slaveowner Henry Overton Wills III, but the request was denied. https://t.co/K7LeRRu9T2

— S (@neufunkaum) June 3, 2020

The University set up the Past Matters Committee ‘to make our historical links to slavery more explicit’ by ‘bringing together students and staff to explore the history of our University and our buildings, and the history and legacy of slavery in Bristol and help shape our response’.

Epigram spoke to Asher Websdale and Shakeel Taylor-Camara, former members of the Past Matters Committee and two of the original petitioners, to discuss controversial memorialisation within the University.

Challengers to the practice of removing statues and building names argue that it runs the risk of sanitising and simplifying an uncomfortable national history. I asked whether inheriting and maintaining these morally complicated objects, like the Wills Memorial Building, would be better for future societal reflection and understanding.

‘You have got to remember both the time in which they were put up and the reasoning behind putting up statues and naming buildings after certain individuals,’ Shak said, ‘which was to honour that individual for their contribution to something.

‘Would we consider naming a building or putting a statue of an individual who has a dark past the best way to educate people on the matter now? If removing the statue is a way of removing the history, then why isn’t there anything else there to educate people of the history? What good did naming the statue or naming a building do for educating people before the petition brought it to light?

‘I don't think that’s the best way to educate people. If there’s not an education about the history of Wills inside that building, then it’s not an education piece. In taking away the name, the history should still be inside the building.’

Asher believes ‘the biggest issue is that people that oppose these movements really struggle to understand what memorialisation is. There’s many ways we can memorialise without paying homage to any of these people. People seem to tie the money bequeathed by Wills as worthy of great memorialisation of him,’ he adds, ‘yet if we think about where this money came from, we have to surely at least recognise that this money has come from an evil atrocity in our history.’

Indeed a key underpinning theme in the recent Black Lives Matter movement is for greater education on the dark histories of both Britain and Bristol. As such, how should students be educated on the University’s historical links to the slave trade through people like Wills?

‘We wanted information directly given to the students. We recommended a talk was held within the Will’s Memorial building in Freshers’ Week, so that students could come along. We recommended calls for colonial studies within students’ first year studies,’ Asher explained.

You have got to remember both the time in which it they were put up and the reasoning behind putting up the statues

‘Our mission was to continue telling history, it was not to erase history. It was to, in some respects, correct the record. There's multiple ways we can tell that story, but the medium in which we're telling it is not only one-sided, it's not only racist, but it's also just ignoring a huge part of history.

‘We really encouraged students that we knew to go out and learn for themselves, but this movement does need to come from within the University.’

In recent months, the University has renewed its efforts examining its links to slavery and how it educates students. In an email to students from Vice-Chancellor Hugh Brady on 11 June, the University committed again to ‘reviewing the names of our buildings’.

The #BlackLivesMatter campaign has served to amplify existing concerns about the University’s history and whether we should rename buildings named after families with links to the slave trade. We commit to reviewing the names as well as our University logo. (1/3)

— Bristol University 🎓 (@BristolUni) June 11, 2020

To what extent this move is genuine self-reflection or an appeasement to the growing calls for action is yet to be seen.

‘It’s very timely for them to say that they are reviewing this, especially with Colston coming down’ says Shak. ‘It’s hard to know where the University’s position would be if Colston wasn't taken down and if other names weren’t removed because they have had hundreds of years of existence to review these matters.’

Asher continued: ‘To me, academic institutes should be leading on these progressive thoughts, not reacting to social circumstances. I find it a real shame that universities across the UK are not at the forefront. They’ve taken some steps, but I think they’ve always been in reaction to something.

‘I would have really liked to have seen Bristol, especially in the last three years since we've been having these conversations, to have been making the kind of statements they’ve just made.’

The drive to address the memorialisation and glorification of divisive figures must be a dual effort between the University and students – in January the University appointed Olivette Otele, the first Black female professor of history, to further examine these links. However, Asher feels there still remains a problem of general understanding.

‘I do think there is certainly an issue within the University that they don't understand how this does impact BAME students, and this has definitely shown in meetings we've had with senior staff members.’

‘But we also want to say thank you to all the staff that did support us, because there were many people who really tried hard and are still working hard. It's great to see that people are still engaging in these conversations and taking it upon themselves to educate themselves.’

‘It’s upon ourselves to have this collective moment where we stand up and say enough is enough. We're not going to tolerate this anymore. We’re going to actively fight against it, and I think that a movement like this can genuinely do that.’

Shak and Asher also expressed their gratitude to fellow petitioner Elmi Hassan for his persistent work and continual support, and to Tallula Reece, who set up the most recent iteration of the petition to rename the building.

For Asher and Shakeel, and indeed many at the University, there will be some optimism that recent events may lead to meaningful change.

Featured Image: Flickr / Tobias Berchtold

Do you think the Memorial Building should be renamed? Let us know!