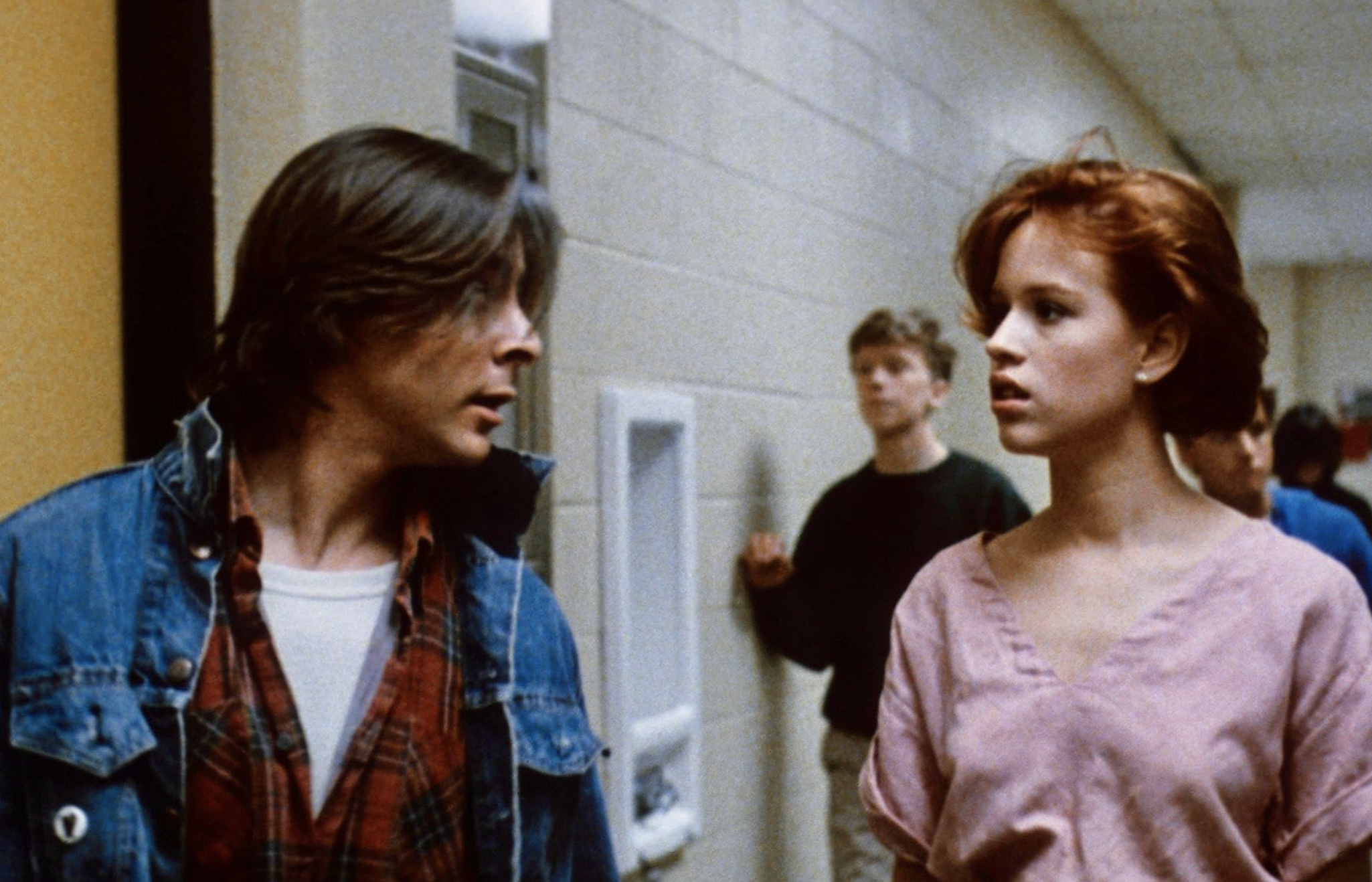

John Hughes’ most seminal work and arguably the defining film of its decade, The Breakfast Club has come under equal levels of reverence and scorn since its 1985 release. So which has it earned more?

Few films have captured a time period more effectively than The Breakfast Club. The release of Hughes’ second film was akin to that of an atom bomb to a sleepy 1985. Its poster became instantly iconic, its soundtrack was ubiquitous and it established Hughes as a major voice in the world of popular American cinema. The film also broke new ground for its deconstruction of high school stereotypes and is often credited with starting a new conversation about mental health among teenagers that continues today.

However, it’s since become the target for a significant deal of backlash, mostly regarding the character of John Bender (Judd Nelson) and his treatment of Ringwald’s Claire Standish. Now that it’s turning forty, it’s about time to do a full deep dive into The Breakfast Club - what holds up all these years later and what should we be willing to leave to the 80s?

The character of Bender is routinely hostile and abusive towards the other four students, especially Claire. Over the course of The Breakfast Club, he repeatedly sexualises her, calls her fat, makes fun of her difficult home life and, in the film’s most infamous scene, sticks his head between her legs without her consent. His abuse isn’t limited to her. He calls Andrew ‘a lobotomy in tights’ and pokes fun at Brian’s sexual inexperience. Fortunately, Hughes does seem to know that Bender isn’t a great guy. He wanted to create a realistic representation of an 80s high school (though notably a very white one) and that obviously had to include some pretty misogynistic and homophobic behaviour.

To present a vision of a high school where everyone got along and no off-colour insults were hurled would have undoubtedly rang false both then and now. Hughes ultimately sees Bender as a tragic character and a product of terrible circumstances. The film details his abusive parents and violent homelife, deftly painting a picture of someone whose sarcastic barbs and acting out are a forcefield from a hostile world. It’s this element that’s aged the best.

Hughes, often accused of presenting rich, upper-middle class white households as the default family setting and re-asserting existing social stratas, reveals the implicit classism of how everyone treats Bender. It’s not just that he keeps a guillotine in his locker and lights a cigarette with his shoe that makes everyone want to avoid him in the corridor. It’s that they know he’s from ‘the wrong side of town’.

However, we run into some problems at the end of the film when Claire falls for Bender and kisses him while he’s confined in a store cupboard. This sudden change of heart from loathing him to loving him essentially comes out of nowhere, having no prior basis in the script. The implication is that she can overlook his rough exterior and see him for the sensitive, worthwhile man that he is.

This wouldn’t be a bad denouement for a film about how appearances can be deceiving if he hadn’t sexually harassed her just a few short hours earlier. Bender never repents or apologises for his actions - he’s abrasive and nasty until the very end, even as the others acknowledge how they’ve unfairly pigeonholed their peers. Again - this does make the story more realistic and saves it from any clanging, eye-rolly moment where Bender falls to his knees in contrition and desperately begs for forgiveness.

However, it also doesn’t justify the fact that the film, especially its indelible final shot of Bender punching the air, fundamentally presents him as a punk hero. It’s clear that so Hughes desperately wanted to end with a redeeming moment for Bender that he had to make one of the other characters do the work of getting the audience to care for him. And, with all the sensitivity of pushing a gamepiece across a tabletop, he forced Claire to fall for him. This robs her of her agency and makes her merely a vehicle for his unearned redemption. And such flagrant manipulation certainly makes that final shot a little more complicated.

The film’s questionable painting of certain characters doesn’t end there. From the very first scene, Hughes makes it painfully clear just how disgusted he is by Allison. He mocks her mostly non-verbal nature and how she doesn’t conform to normal standards of behaviour. He mostly only sees her as a sight gag, adding in nasty gross-out moments like her shaking her dandruff over a drawing. However, as is the case with Claire, the final ten minutes is what really throws the character under the bus.

Despite seeming to be totally at peace with her unconventional look and aesthetic, she lets Claire give her a complete (yet totally unprompted and uncalled-for) makeover, at the end of which she perfectly fits the bill of the pretty, unassuming girl-next-door. Moreover, it fits into a problematic trend of male directors constructing sequences where a plain, bookish girl suddenly gains value when someone transforms her into a beautiful, swan-like model who guys finally notice. The Breakfast Club is arguably the worst offender here, both because of how unnecessary the transformation is (it doesn’t affect Allison’s arc) and how relieved Hughes clearly is when it happens.

He seems to be saying ‘Thank god that weird goth let a nice, normal girl turn her into someone that guys would actually want to go out with!’ This is reflected in Claire’s line ‘You look so much better without all that shit over your eyes’, clarifying the film’s revulsion over Allison’s earlier stylising even further. While Allison responds to this by saying ‘I like that black shit’, Hughes clearly doesn’t care. It doesn’t matter if a girl likes the way she looks - she must get outside validation first.

In the end, it’s a mixed bag on the rewatch. I’d certainly recommend giving it another spin, especially if it’s been a couple years since you last watched it. In hindsight, it’s clear that Hughes wasn’t quite as gifted as a director as he was as a writer - the pacing here is all over the place and he struggles to keep the single-location setting visual dynamic for the whole runtime.

Similarly, I’ll always prefer Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), which holds up much better on the rewatch in its distinctly progressive attitudes towards sex and high school cliques. But The Breakfast Club still retains its importance - both as a time capsule for a nostalgic period and a reminder of how much things have changed. How, while we might be wistful of the music and fashion of the time, it’s necessary to move on from the social standards of 1985.

Featured Image: IMDb

Do you think the teen classic still holds up in 2025?