By Jenna Baker, Second Year Film and English

Racial segregation is alluded even from the opening credits introducing the production company in large black lettering against a white background, reminiscent of Zora Neale Hurston’s quote, “I feel most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background,” and more pertinently in artwork by Glenn Ligon.

Cinematography in this film remains unpredictable in the most profound way. Instigating the film is a lengthy montage of close-ups, where childlike innocence is alluded to and quickly destabilised when a child falls from a playground climbing apparatus and when Elwood’s (Ethan Herisse) grandmother reaches for a knife in bed. Audiences are immersed into Elwood’s world through POV shots. The innocence of childhood is felt, but there is an underpinning of something darker, threat is established.

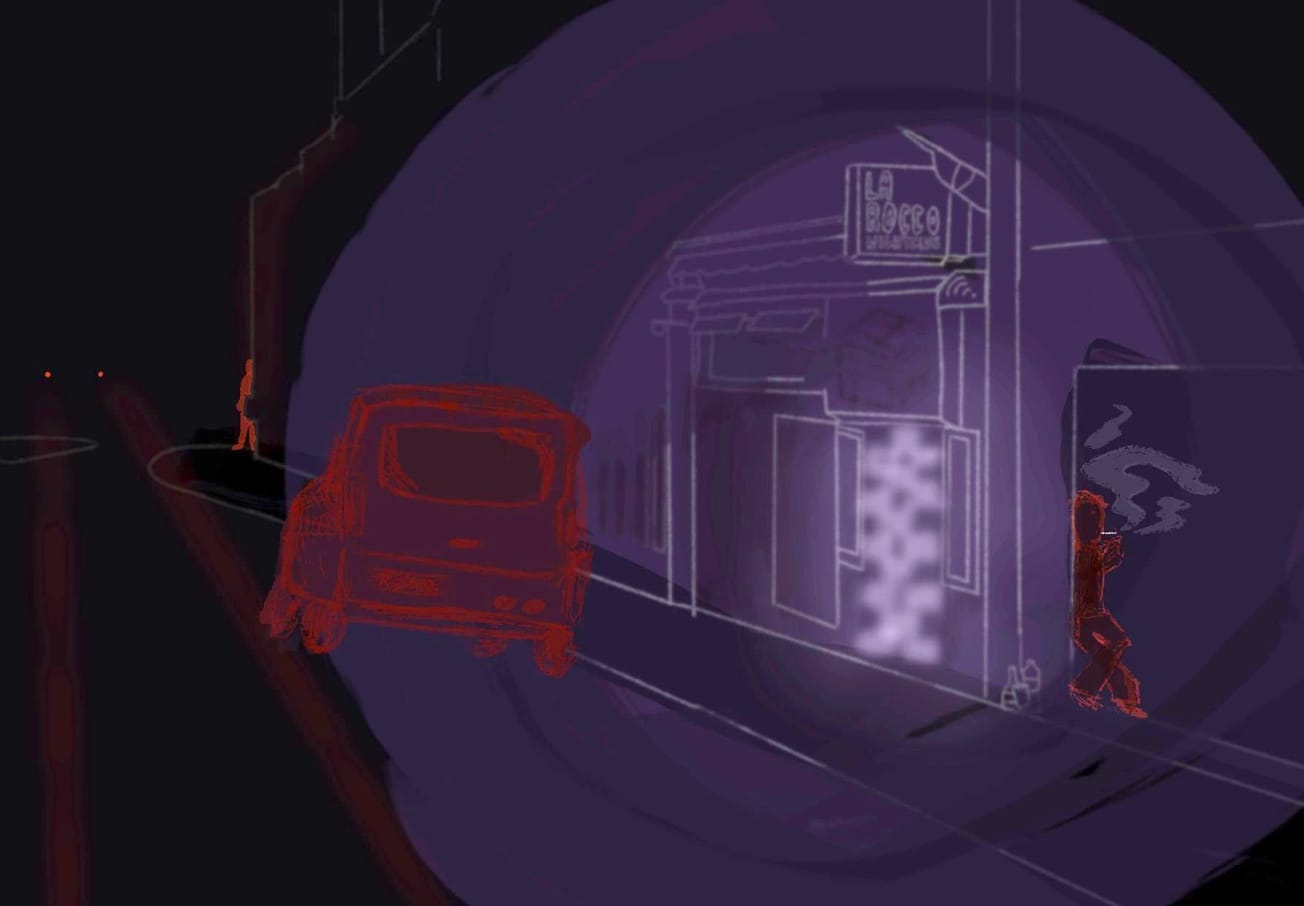

Shots display Elwood’s reflection early on, in an iron, watching Martin Luther King through a shop window of TVs and on the bus. Whilst audiences are encouraged to be immersed within his perspective, there is an understanding that this is an experience of a young black man in a particular sociopolitical context, allowing us to feel with more power his experience, but recognise it is never our experience to claim. Victimisation by police happens early on in the film, as Elwood and another black boy are poked at with a stick humiliatingly by a smug looking police officer. Simplistically powerful, shots such as the flyer from Melvin Griggs school stuck by a magnet to the fridge slowly slipping down, foretell its unlikelihood, the gradual downfall of Elwood’s hopes for a better future.

Before Elwood is unjustly detained, his Nana (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) cuts a cake. Extreme close-ups display her scraping off the excess; the sound of scraping is amplified and disturbing, suggestively, her attempting to scrape away whiteness, that has infiltrated the peace of their lives. Sudden contrasts in shots come when Elwood is taken to the detention centre, looking out through the barred section of the car, and once the other white passengers exit, anxiety is amplified through intense high-pitched violin. Audiences are invited to feel the entrapment here; it is intense and unsettling, but the stark contrasts in confinement amplify larger racialised implications, as the segregated buildings vastly differ in size and stature for the white and black inmates.

The most powerful moment of the film perhaps is when Elwood first experiences direct physical violence. Anticipation is at an uncomfortable high, as the other boys are beaten. It is not shown directly, but this only produces a more stirring response, displaying a close-up of the Bible, a suggestion that God is watching this immorality strike. Sounds of fear in murmured whispers and panicked breathing intersperse with shots of complete blackness, perhaps in direct opposition to this horrific enforcement of white domination. Abruptly, the POV shots halt: we view Elwood standing, about to be beaten, and audiences are removed from this experience of direct physical violence. Narrative consistency is suddenly destabilised; audiences are drawn out from the allusion that this was their experience, evoking a forceful, stark reminder of privilege. Immersion has been so effective within the use of POV shots previously, that the removal of thus is so shocking that it produces a visceral sting.

Flashforwards later in the film uncover the narrative of Elwood’s friend, Turner (Brandon Wilson) in the future, where POV shots now take place with his head still in the frame, from behind his head. Blocking some of his view from the audience perspective is jarring and certainly unusual, however there is an indication that Turner has now moved from the experience itself to that of being the experienced, or consequently, traumatised. The POV shot is altered and suggestively, Turner’s perspective on life has permanently altered from the experience.

Ramell Ross creates a film so intensely unsettling in its portrayal of the lifelong impact and experience of racialised violence, it’s hard to leave the cinema without being physically affected in some way by its shock. Wrongfully named as a school, 600 students went through the real life institution each year within its 110-year existence, many of whom were sexually or physically abused and even some, murdered. Ross seems to tell the powerful story of real-life suffering through a unique audiovisual narrative that through its use of perspective, creates an unsettling affect that is inescapable.

Featured Image: IMDb

Have you checked out the critically acclaimed Nickel Boys?