By Jenna Baker, Third Year, Film and English

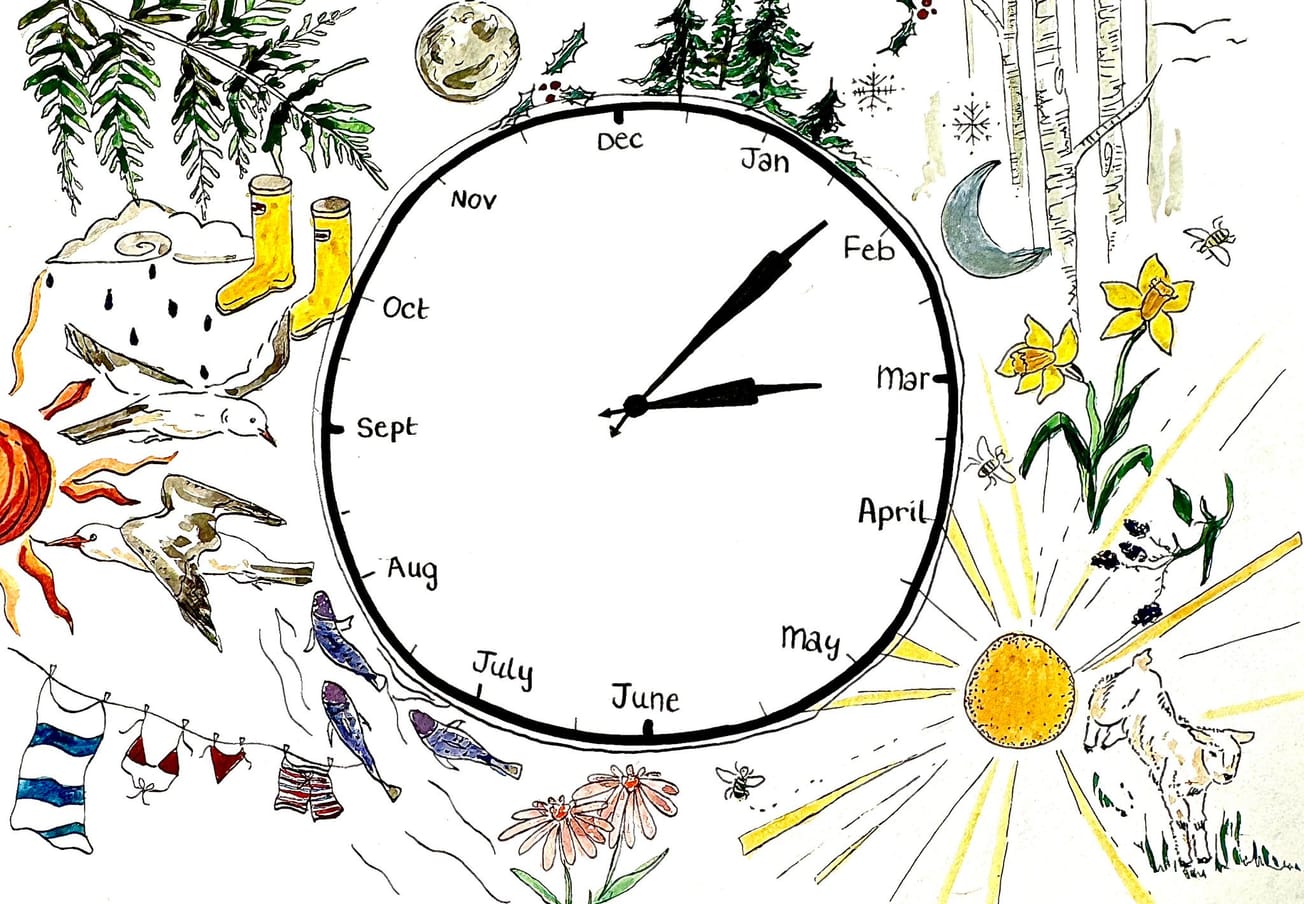

From all corners of the library, the echoes of keyboards and coughs are jolting my focus. A persistent drilling headache consumes me, because my blood sugars are soaring and they haven’t budged since this morning. I reflect, Did I eat a sugary breakfast or forget to give my insulin? No. I pre-bolused (administered insulin in advance) to stop the usual breakfast spike and pre-bolused 10 minutes before I even started to sip my coffee. I shrug and attempt to get back to reading. I notice now that I feel nauseous too. My eyes start to droop and the stinging yellow lights of the library magnify the pounding in my head. Maybe I don’t need to get this work done today. I head home to take a nap. Roughly three hours later, after resting for a while, I attempt to do some work again and I’m interrupted by my blood sugars dropping rapidly. Debilitated by hypo symptoms, I feel weak, dizzy and faint. I’m exhausted. Everyday I experience these ups and downs.

Perfectionism is a trait that I know I share with many of my peers at university. However, my perfectionism stems from a need for survival. When perfection in my blood sugars is not met, my daily life is interrupted to the extent that it impacts my ability to work, look after myself, and socialise, the effects of which often leave me drained and burnt out. In worst case scenarios, a lack of perfection and control can lead to vomiting, hours of nausea and headaches, A&E trips, and potentially a diabetic-induced coma (keto-acidosis). Measured literally in numbers, I have had no choice but to rely on my own control and strive for perfection.

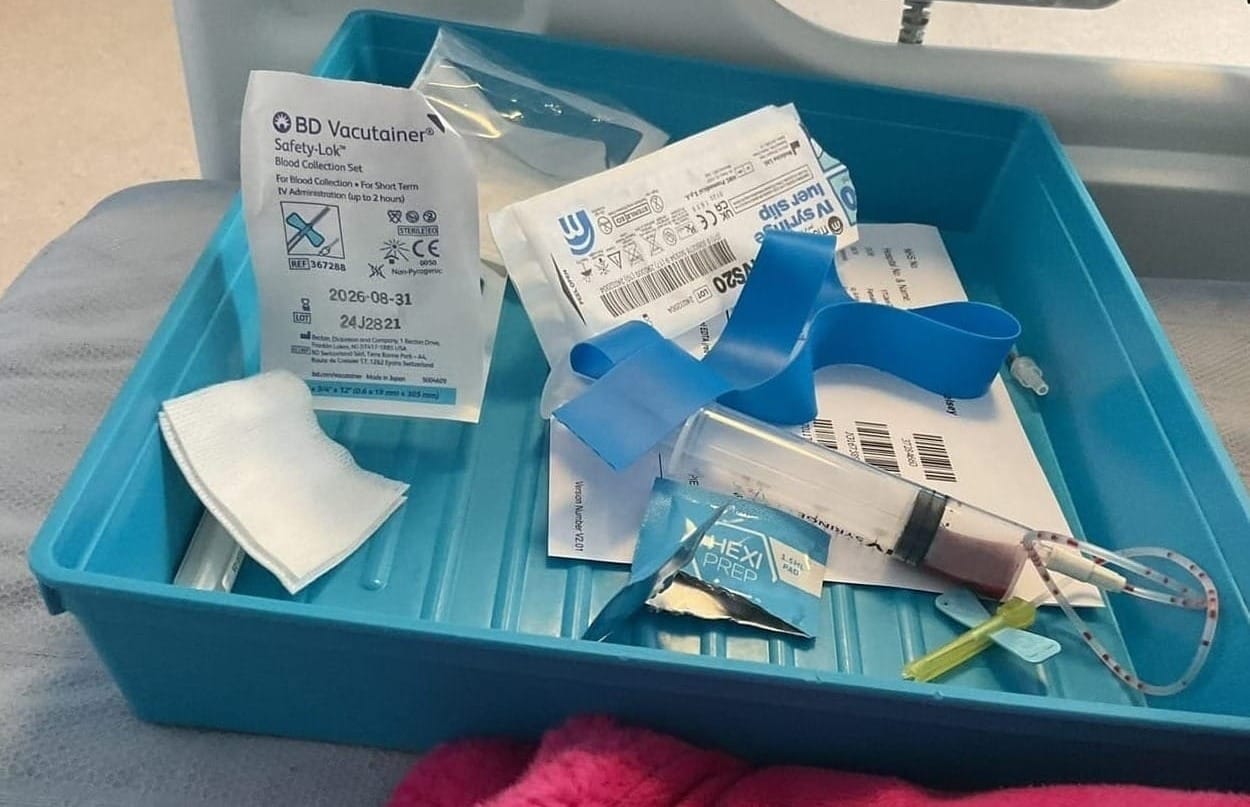

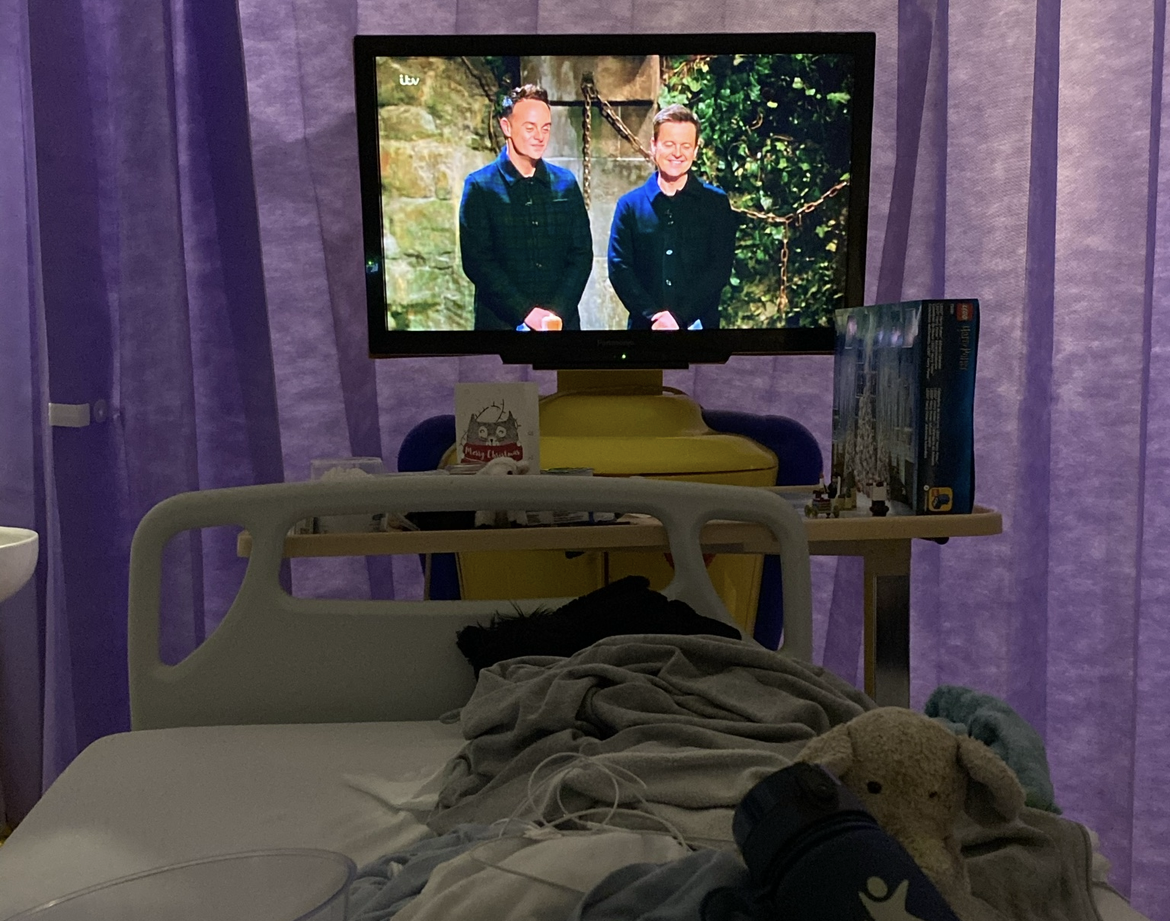

Ever since I was six years old, my body has been a site of removed agency. I have often felt violated being poked and prodded by doctors; I am desensitised to needles, alcohol wipes, drips, and annoyingly sticky and painful adhesives because my health must be monitored. The bitter, clinical stench of insulin (which I smell every couple of days when I change the site of my insulin pump) is embedded into memories of childhood. I am so grateful for the healthcare in this country, but the psychological toll is inevitable and I don’t always feel that doctors consider this. I remember one instance when a doctor made a decision about my insulin and then later complained about it, accusing me of administering the change. When I responded, ‘that was you,’ he mocked me for being ‘sassy.’

So much has changed since moving away to university, with both academic and diabetes-related challenges becoming more gruelling. I often feel the urge to either overwork and do all or avoid it completely and do nothing. When it comes to diabetes control, doing all is really the only option if you want stable blood glucose levels. There is no in between; as soon as you start to take a step back or make mistakes, the physical and emotional symptoms begin to appear and the potential for risk increases. As well as the anxiety and guilt I feel if I don’t administer complete control, alongside the immediate physical symptoms, the risks of prolonged unstable blood glucose levels include sight loss and potential blindness, hair loss and at worst, losing the ability to walk.

Burnout has always been a persistent struggle, simply exacerbated by the pressures of academia. Having to carry equipment is second nature to me now, but a clunky device certainly instilled a feeling of difference in the playground. Shoulder pain has thus become as familiar to me as the repeated irritating beeping noise of my insulin devices at this point. When I came to university, the one thing I was most excited about was finally being able to embrace my own independence. Despite relative independence from an alarmingly young age, a reliance remains when you still live with your parents, especially when they have been your caregivers in a much more survival-oriented sense.

It is not unknown that excessive drinking is embedded into university life, especially in first year. I had already been drinking at school, however I didn’t quite recognise the level of danger I could be in if I hadn’t had my parents there to check on me. I can only express my gratitude to them, as I don’t think I had ever fully comprehended the extent to which alcohol can interfere with your blood sugars. Alcohol causes your blood sugars to rapidly increase, and then many hours later, rapidly decrease. This can be dangerous, as many hours later you might be asleep and not wake up to the alarm, or be too intoxicated to notice that you are having a hypo (the symptoms are actually quite similar but a hypo avoids the fun parts). I’m quite astounded at the amount of drunken nighttime hypos I’ve survived. When a night out becomes a fearful challenge, it can be tiring and difficult to integrate socially. It’s also easy to feel like a burden when you need to make sure someone knows how to care for you. Opening up to people around you can help minimise that burden, and connecting with other diabetics has been a great way to feel understood - I recommend Facebook groups!

I could write much more extensively about the complex ways diabetes has impacted me. Chronic illnesses can severely complicate otherwise simplistic situations. Opening yourself up to support is essential, as everyone deserves to be heard and understood. Whilst everything may appear under control, often, I feel swanlike. Masked by an image of composure, internally I am pedalling in what feels like a frenzied rhythm, just trying to stay afloat.

Featured image: Epigram / Jenna Baker

How else can we ensure that those with diabetes are supported at university?