By Noah Robinson, Second Year, Law

In 2017, police mistook Ras Judah, a 63-year-old Rastafarian elder of the St Pauls community, for a criminal suspect. He was brutally tasered in the face whilst walking his dog and trying to enter his own home.

The incident was captured by Judah’s neighbour, Tom Cherry, and the video quickly went viral, sparking outrage and was watched by millions on mainstream news reports and social media.

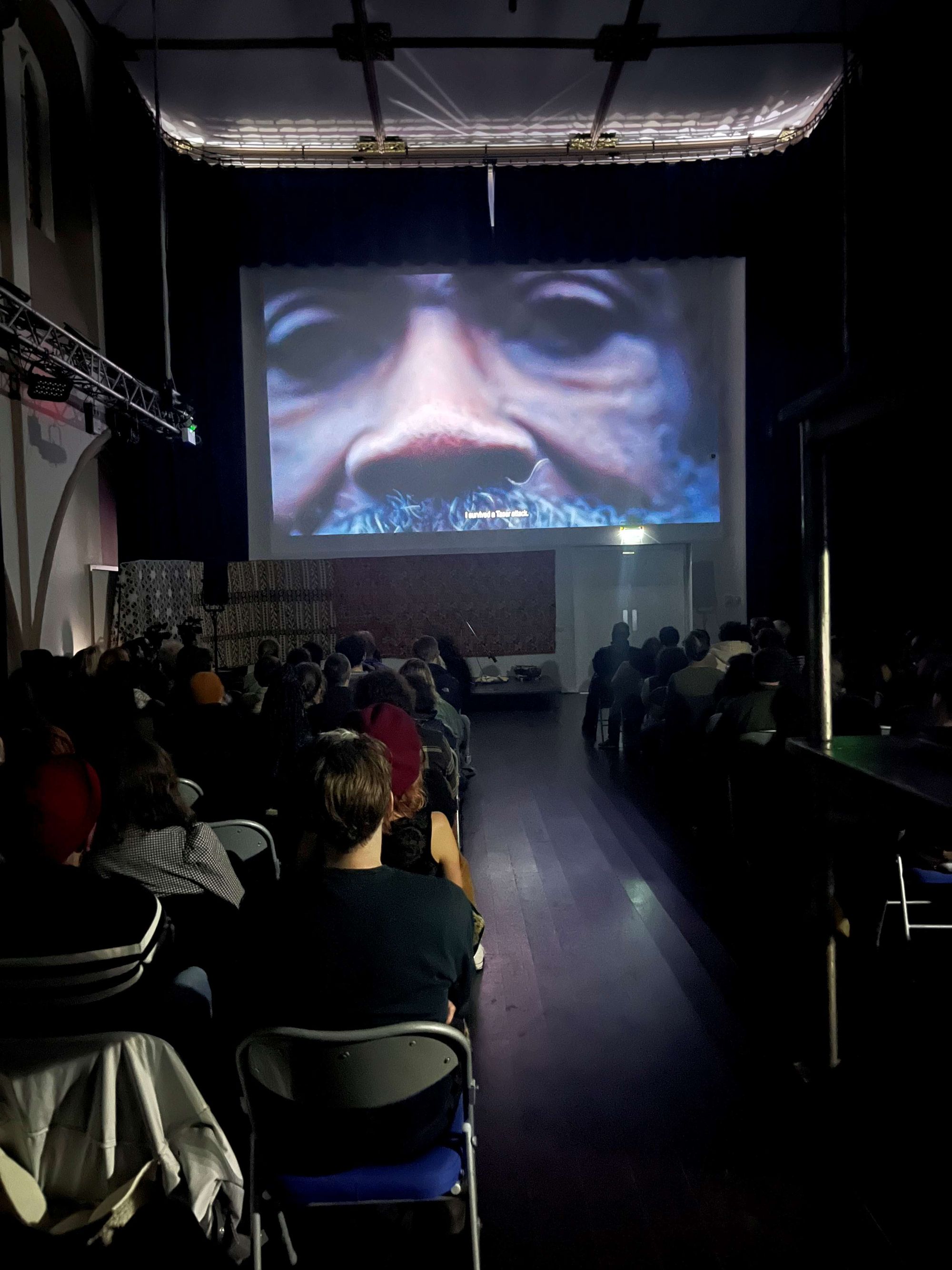

Directed by Bashart Malik, with producers Christian Robino and Saleh Mamon, the Bristol-produced documentary film I am Judah is a deeply personal narrative, drawing on a verbatim script, poetry and expertly crafted cinematography. Originally premiering in 2022, the re-showing of the documentary took place at Trinity Centre.

Malik seeks to present an intimate portrayal of one man’s life against a long line of injustices faced by racialised people, from the transatlantic slave trade, to the arrival of the Windrush Generation, to the St Pauls’ uprising in the 1980s. It culminates in a necessary and painfully truthful expose of both the historical and the enduring nature of racism today. The documentary is not simply about Judah but the system-wide failure of the over-policing of Black communities and how we seem to simply accept the status quo.

But with the recent expansion to police powers, the abuse of stop and search continues, threatening to push the fundamental distrust of the police past repair.

The painful tragedy of the documentary is that the officer who discharged the taser was later found not guilty at criminal trial and cleared of misconduct, in what she claimed was a case of mistaken identity. But as the film makes evident, it was due to Judah’s race, as the officer identified Judah as another Black man who looked nothing like him. It warrants exposure and illustrates how close to home these incidents are.

The film charts the course of Judah’s life from his birthplace of Saint Mary in Jamaica to arriving in St Pauls in Bristol and residence in Easton. Growing up in the 1970s, Judah was no stranger to contact with the police. He was falsely accused of assaulting a police officer, despite eyewitnesses saying the contrary. The common occurrence of over-policing for Black people led to the St Pauls uprising in 1980s. The historic causes of racial tension, poor housing and distrust from Black youth echo the contemporary concerns of the film.

Driven by the growth of Black consciousness and events at home and abroad, Judah became actively involved in his community to improve race relations in Bristol.

As well as founding the St Paul Sports Academy, Judah became one of the first Black people to work at Bristol City Council, in his role as a Sports Development Coordinator. He was actively involved in the establishment of the Race Relations Advisory Board in the 1990s, which aimed to enhance relationships between the Black community and law enforcement.

This is, no doubt, the most telling irony of the documentary. As someone who was well respected and known in his community and had a profound impact of improving race relations with the police themselves, it is shocking that he was mistakenly identified as the same criminal suspect, a further three times in the same year.

The camera footage of the taser incident is intermittent throughout the documentary, visually depicting the reliving of the initial traumatic incident and the emotional labour of the moment. There’s a callous simplicity in this violence. And whilst the discharging of the 50,000-volt taser lasts only a few seconds, its impact on Ras Judah’s health is long-term, causing permanent speech disfigurement, a mini stroke and chronic pain.

Although, the Avon and Somerset Police declared itself institutionally racist in June 2023, the documentary makes clear that this does not go far enough. Those involved were not held to account and justice was not seen to be done. The law fails to counter excessive use of force and only seeks to uphold the system as it is.

The closing images of the film concretely show a broken sense of trust between the police and the communities they are supposed to protect. Snapshots of Judah in nature feature throughout, often when speaking about his connection to his ancestral roots and strong sense of spirituality. After the incident, Judah no longer feels safe walking in public alone, accompanied always by his friends. He speaks of returning to his homeland in Jamaica to heal. It’s a raw reflection on the deep-set trauma of the pervasive, consistent and violent nature of over-policing. At this point, the relationship between him and the police is irreparable.

I am Judah is a powerful testament to one’s man life dedicated to change but speaks more broadly to the desperate need for fundamental reform to the systems that evidently only protect some of us.

Featured image: Trinity Bristol / Sam Prosser