By Sophia Izwan, Second Year Mathematics and Computer Science

We all know the not-so-old adage, ‘new year, new me’, and for some, that means a new hobby (or five) to obsess over. The journey into journaling, crocheting, or painting inevitably begins with a purchase: a fresh notebook, a starter kit complete with hooks and yarn, or vivid watercolours, each promising to unveil the most creative version of ourselves. With the rise of consumer culture however, navigating to the checkout page has become almost as engaging as participating in our chosen crafts, to the point that we risk conflating the two.

The fact that creative hobbies require spending money isn’t an issue. It’s only when consumption threatens to replace creation that a problem arises. Sometimes, just beginning is fraught with hesitation. Especially amongst novices, there is almost the concept that the ‘right’ equipment is needed before anything meaningful can be done. Prioritizing aesthetics is encouraged in modern society, oftentimes leading to novelty purchases that are soon relegated to the bottom of a drawer.

With the advent of starter kits, the barrier for entry has never been lower. On the surface, this accessibility appears liberating. But it often results in shallow beginnings, where a box of supplies and a pre-written pattern is the extent of the hobby experience. I am not exempt from this tendency. As I write this, a paint-by-numbers set and felt needling kit sit untouched at the foot of my bed, acting as reminders that accumulating premade kits can replace the more deliberate practice of owning a needle, thread, and making do with what you already have.

‘The solution? Manufacturing desire itself’

Consumer culture as we recognise it today is relatively recent. Prior to the 1920s, goods were typically scarce, so the average person hadn’t much need or want of anything more than the essentials. However, post-war production led to an abundance of commercially-available products, potentially stagnating economic growth. Supply and demand were out of balance. The solution? (At least, the one conceived of by ‘consumption economists’ and leveraged by many businessmen of the time). Manufacturing desire itself. People are encouraged to constantly hunger for more, because at its heart, consumerism is a paradigm rooted in dissatisfaction. To this end, modern man is not much different to Tantalus—tormented by the unachievable promise of fulfilment.

This sense of incompleteness is perpetuated by social media platforms where consumer targeting has been refined into a science. The medium, fraught with personalised advertising, lends itself to impulse purchases. Truthfully, we sometimes don’t have time for our hobbies, or we find ourselves without the bandwidth to meaningfully engage with them. In these moments, browsing products may feel like a shortcut to ‘do’ the hobby. Buying, then, becomes a stand-in for doing.

It is important, however, to not lump all spending under the umbrella of mindless consumption. The line between hobby and excess is largely drawn by intent. At its core, consumerism is defined by waste—spending for spending’s sake rather than utility. If materials are used and contribute to one’s own enjoyment, it cannot meaningfully be called waste. The distinction lies not in what is purchased, but what is done with it.

Understanding this difference makes resisting the siren call of temptation possible, even if it remains difficult. Before proceeding to checkout, it is worth pausing. Ask yourself whether the item in your cart fulfils a genuine need or whether it merely caught your attention for a moment. More often than not, these desires are fleeting; the object itself fades from memory within days.

The value of a hobby lies not in the acquisition of materials but in the act of creation itself. Consumer culture encourages the commodification of creativity, treating it as something to be bought, used, and ultimately discarded. While this system is deeply ingrained and unlikely to change overnight, our individual relationship with it remains malleable. The joy of creation, after all, cannot be outsourced to a checkout page.

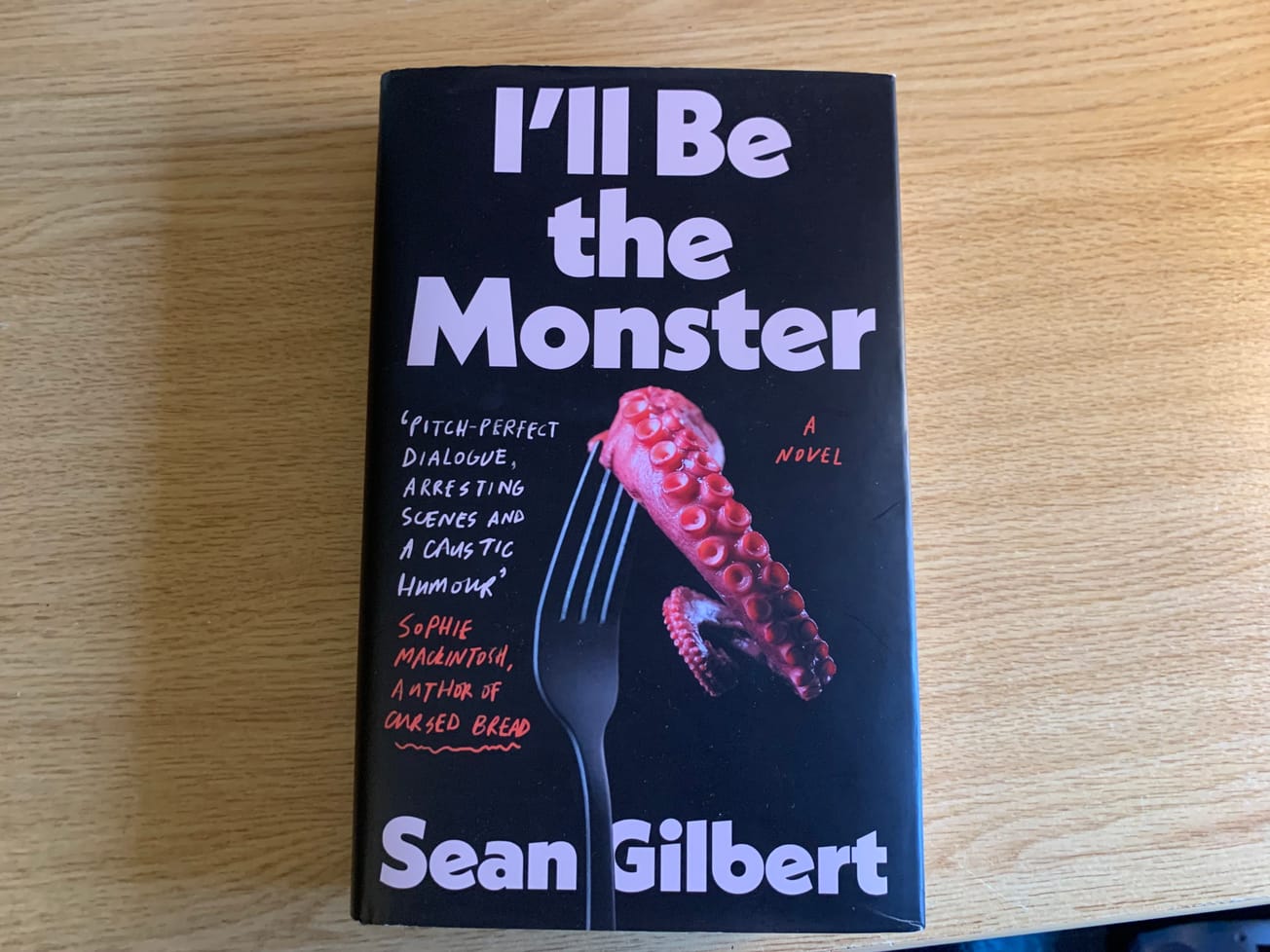

Featured image: Sophia Izwan

Have you taken up a new hobby this year?