By Robin Connolly

As the next installment in our Histories of Bristol series, Robin Connolly explores the origins and development of Black history from a peripheral topic to a celebrated, dedicated history month.

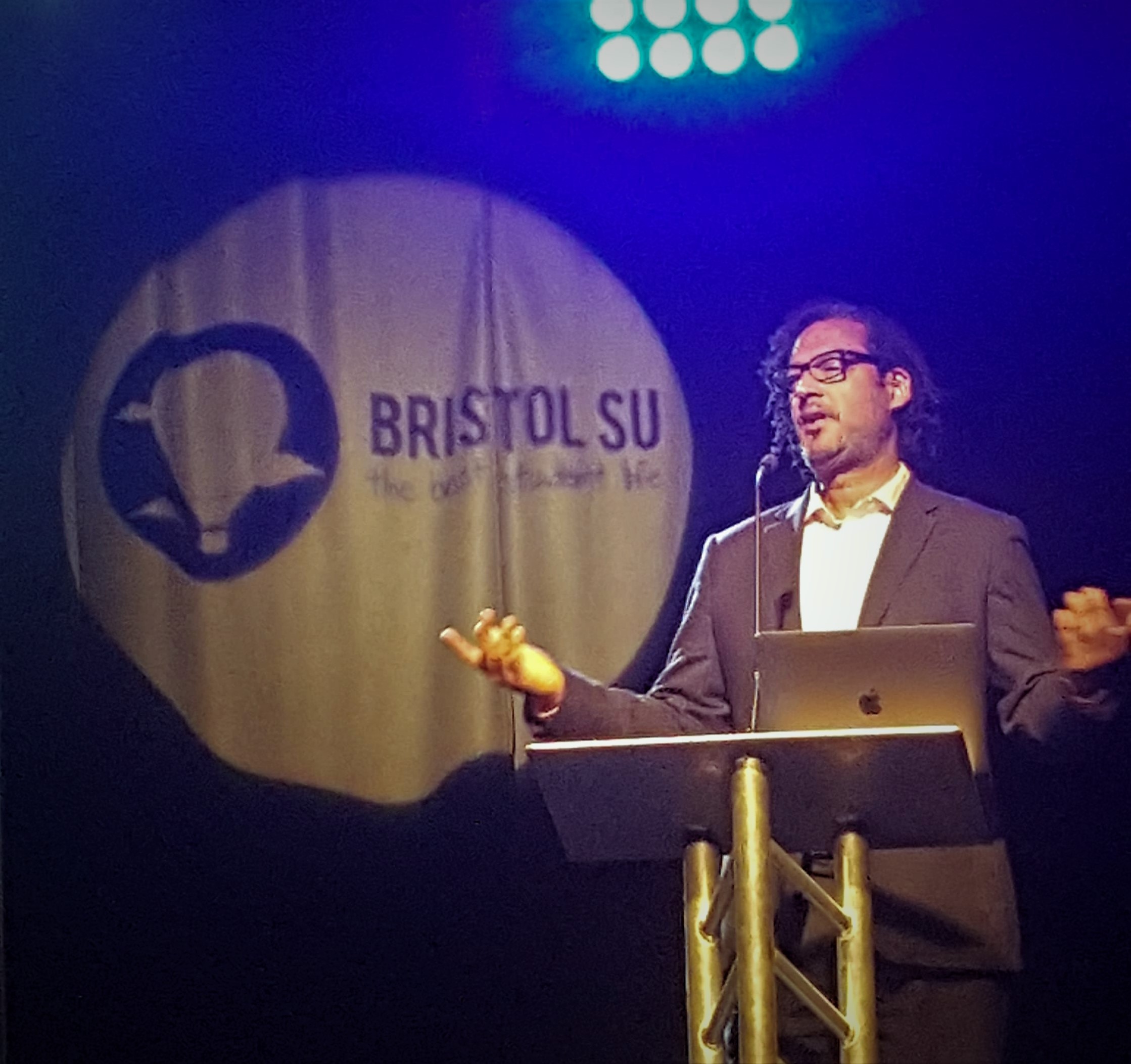

Last Week, historian and author David Olusoga gave a lecture at Bristol’s Students’ Union as a part of the Black History Month programme of events. He spoke about how black people have been overlooked within the British historical narrative, despite the roles they have played in shaping our nation. He argued that history is a place where we go to feel good about ourselves.

David Olusoga delivering his insightful and jarring lecture at Bristol SU last week

So, although black history and British history should be synonymous, the dark pasts of slavery and racism in British history have been pushed aside, to avoid discomfort for the white majority. Much of the British history we were taught at school was glorious – of white conquest, victory and the strength of British values. This history is the one we know, the history which underpins our national identity. It is comfortable and easily glorified.

'I wanted to find something that gave me a warrant to exist, to be in Britain. After suffering a profound sense of rejection.That I couldn't exist. That I couldn't be black and British.' @DavidOlusoga talks movingly about Staying Power in our new podcast: https://t.co/VQ68GkpopV pic.twitter.com/t3sM9FGNXI

— Pluto Press (@PlutoPress) October 12, 2018

What is less comfortable is facing up to the fact that white history is inseparable from the history of black slavery in this country. It is perhaps easy to ignore history, to argue that it is irrelevant to our lives today, when we live in an age that encourages constant forward thinking and development. However, some of us will have had relatives who were slave owners, traders or who otherwise had investments in the trade of our fellow student’s ancestors. This makes our history mutual. This makes black history equally as relevant to those of all races in Britain, as we are all somehow associated with its forgotten past.

The controversy surrounding the removal of Colston's statue from Bristol city centre is an example of the relevance of acknowledging a difficult relationship with black slavery in Britain'The statue was put up in Bristol in 1895, several years after Colston’s death'

— Countering Colston (@CounterColston) October 14, 2018

For this journalist, 174 years is 'several' https://t.co/M9lrZer6zU

Black History Month was first celebrated as Black History Week in 1926 in the U.S, before evolving into Black History Month in 1969. It was an attempt by historian Carter G. Woodson to reclaim these black histories that have been overlooked in textbooks and academic works. However, it wasn’t until 1987 that the first Black History Month came to the UK. Proposed by Ansel Wong of the Strategic Policy Unit and hosted by Linda Bellos, the leader of Lambeth Council, Black History Month was to be distinctive from its sister month in America.

Black History Month was founded to highlight the unknown, undiscovered histories of black people in Britain and to push for a revaluation of the histories we blindly accept as fact, without attempting to understand perspectives buried in the depths of the archives.

There are so many of these voices which have been both lost and actively silenced through the traditional telling of white British history. For example, in Bristol itself, it has been estimated that between 1698 and 1807, over 2,100 ships which would come to transport over 500,000 Africans - more than the entire population of Bristol today - left the city’s Port en route to Africa before sailing the Middle Passage to the Americas. They were not considered people, but instead ‘black cattle’ on a stock exchange where livelihoods were traded for profit.

BHM: 'immerse ourselves in what is not only black history, but a universal history'

Our geographical separation from the destinations of these slaves meant we could easily sweep the ugly truth of the origins of this revenue under the carpet – most British people saw the money without the blood. It is easy to see history in the same way – to celebrate the glory of the abolitionist movement without appreciating the role our ancestors may have played in the international slave trade.

Although Black History Month is as relevant as ever before, this year’s events are perhaps more accessible to the British public than in previous years. Prominent news stories such as the Windrush Scandal, discussions about statues such as that of Edward Colston and Cecil Rhodes in universities and the death of Aretha Franklin have created the perfect opening for us to engage with black histories, to immerse ourselves in what is not only black history, but a universal history.

The history of black people in Britain is currently only available to those who go out of their way to seek such information out. One of the goals of Black History Month is to strive for a national consciousness that encompasses fully the racial past of our country.

Bristol SU has a unique and wide range of events planned for this years Black History Month, from Monét X Change to a guided tour of Bristol’s slave trade, from Afrofusion dance to a discussion panel with some of the brightest black women in the creative industry.

Featured Image: Wikimedia Commons / Johnny Silvercloud