By Ellie Spenceley, Second Year, English

The Croft Magazine // This Eating Disorders Awareness Week, we reflect on how lockdown has forced us to spend a lot of time with ourselves. With this many of us have been pushed to confront our minds and bodies in a way that we’d once been able to avoid. For people with pre-existing struggles with disordered eating, body dysmorphia, weight and body image, isolation has been a particularly peculiar time.

Content warning: disordered eating/eating disorders, body dysmorphia, weight, depression

Lockdown has made it impossible to escape the often toxic self-critical narrative in our heads concerning our right to take up space in the world, especially now that the world we are legally allowed to live in has shrunk significantly in size.

As my world has gotten smaller, my body has conversely increased in size as a result of antidepressant medication, boredom eating, and a decrease in physical exercise that used to come naturally as a result of the daily commute to university as well as socialising. My ability to healthily process this without retreating back into old restrictive habits or agreeing with the negative voice inside my head has been put to the test, as has the sturdiness of the road of recovery from past disordered eating I thought I was walking very safely upon.

As many people in recovery from an eating disorder will be aware, no matter how far you distance yourself from the worst parts of your struggle, the possibility or threat of relapse always seems to linger. Embracing a softer body without collapsing in on myself in fear is difficult, but I am doing it with a commitment and a strength only I will ever be completely aware of.

Since the first lockdown in March 2020, I have gained around two and a half stone. I am reminded of this every time I pass the mirror beside my bedroom door, every time I put on jeans I know are a size 10 or 12 as opposed to the six I was comfortably able to slip into in 2019, and every time Snapchat shows me a memory of my first year of university when I had a flatter stomach, smaller waist and a bigger gap between my thighs. I was even skinnier before that, but in an impulsive reclamation of power when I was about 17, I removed every photographic piece of evidence that I was ever that dangerously malnourished from my camera rolls and archives.

The omnipresence of the male gaze, and the many desirability complexes it instils in young women, is quite terrifying. It takes away the ownership you have over your body without you even realising it

Though I was recovered in large part when I arrived at university, upon reflection it seemed a conditional form of recovery. Self-acceptance on the basis that I didn’t exceed a certain size, that my waist remained a 24, that as long as I was small where it ‘mattered’ I could gain some weight where I, or society, considered it to matter slightly less. This form of self-regulation differed from the one I experienced in my mid-teens – back then my eating disorder thrived on rivalry and proving to myself I could reach new lows. As I graduated into adulthood, the factor that sustained my body fixation seemed to transmute into a desire for external validation, particularly that of men.

With multiple factors contributing to a change in body shape during the ups and downs of this pandemic, I have been mostly alone in dealing with this. This has led me to confront the reasons behind my compulsions and question the extent to which I want my body to be small for myself, rather than for someone else’s gaze. The omnipresence of the male gaze, and the many desirability complexes it instils in young women, is quite terrifying. It takes away the ownership you have over your body without you even realising it.

Spending so much time with the company of nobody but myself, I have experienced a sort of mental shift induced by a form of anger at how prevalent feelings like this are among women. We are conditioned to view ourselves through a gaze that is not our own and listen to the commentary we subsequently receive about our desirability, believing it to be indicative of our worth.

Over the past year, I have probably looked at myself more than anyone else has viewed me. I have had time to readjust my lens and realise how performative a lot of my physical behaviour was prior to the pandemic. I have realised that sex should be about intimacy and pleasure and that it has extremely little to do with whether my stomach has rolls when I lie on my side. In the same light, I have attempted to reclaim my love of food and the pleasure it brings me, something I can trace back to childhood and that I have attempted to deny for so long.

In short, I have acknowledged and validated the urgency of my appetite as a woman, and the right I have to satisfy it against the odds of a voyeuristic society that wants me to look small and pretty even at the expense of me having ownership of my life and decisions.

Why should my productivity affect what I’m allowed to eat? How is it helpful for me to force myself to tire out my body just because I got less work done that I’d hoped?

It feels like I have discovered a new layer of recovery that regards self-assertion, boundary setting and a re-evaluation of the intent behind my physical presentation to society. This form of recovery is one that even those who may not have struggled with disordered eating will still be able to relate to in a broader sense.

For those of us with a history of eating disorders or body image issues, earnest recovery seems to come when we are adamant on self-reflection. I spoke to a committee member of Bristol’s Beat This Together Eating Disorder Awareness Society who made a point that resonated with me about restrictive tendencies often carrying a punishing or compensatory tone, and how she had learned the importance of talking back and questioning what they were telling her to do: ‘if I had an unproductive day and jumped to the conclusion that I now couldn’t have pudding, or had to redeem myself by going for a long walk or run, I would be able to pause on the negative thought and dissect exactly what it meant. Why should my productivity affect what I’m allowed to eat? How is it helpful for me to force myself to tire out my body just because I got less work done that I’d hoped?’.

She also said that the time the pandemic has given her to self-reflect ultimately taught her to value herself more and realise her worth was composed of so much more than just her ability to put her body to extremes, and that the best way she found to combat it was to always do the opposite – ‘feel unproductive and consider skipping dessert: eat dessert.

Lacking motivation because you’re tired so you feel you have to force yourself to complete a long workout: challenge the thought by resting your body. By doing the opposite to irrational, disordered thoughts, we show our brains what worries us actually has no power, and this slowly leads to neural rewiring, which in turn means the negative thoughts become less frequent’.

It seems that looking in the mirror and finding something to feel bad about is often an inescapable and thus common feeling

The society we live in is plagued by visual insecurities, and very few of us are immune. Whether these insecurities are in regards to our weight, face, body shape, etc, it seems that looking in the mirror and finding something to feel bad about is often an inescapable and thus common feeling.

With social media and influencer culture being so prominent these days, an environment of comparison has been bred whereby we never feel up to standard because the standard is always moving higher. It does seem to be the case that a counter-culture of anti-fatphobia, body positivity/neutrality and an overall decolonisation of beauty standards is emerging, particularly in feminist and anti-racist online spheres, but the question of how extensive these movements are beyond the echo chambers we as young people often construct for ourselves remains to be answered.

I know my experience with body image in lockdown does not mirror the experience of everyone who has previously struggled with body image issues. I spoke with a number of friends who told me quarantine had intensified their unhealthy relationship with food, with the isolation giving them time to think and thus fall back into old habits in order to ward off any weight they may gain through inactivity. In a global situation as unprecedented as this, it can be easy to resort to calorie counting to cling to some form of control in a world that has taken so much power away from us. With a lack of stimulation that acts as a distraction from unwanted thoughts, old habits can easily reappear.

Perhaps I am privileged in the sense that I have stumbled upon influencers who discuss these issues and that my university friends engage with similar content. We clearly still have a way to go in society with regards to the way we collectively view ourselves – even as I reclaim my power in the ways I have shared here, I cannot deny that self-compassion and prioritising myself is a daily, conscious and often arduous effort, and one that has many setbacks.

My bigger thighs come from Christmas nights sharing cheese and pickles with my dad, my change in dress size from the evenings spent eating snacks and drinking wine with the company of friends over Zoom

I am an educated 20-year-old woman who has had to go through a lot of personal pain to get to this level of understanding, and it is a wish close to my heart to one day see a generation of women come of age in a world where they do not have to go through as many stages of unlearning in order to seek and someday find self-love.

As I sit and write this article, I am eating a piece of chocolate my dad has handed me as he walked past my bedroom door. I rejoice in the small freedom of this action and the progress I have made since I was a vulnerable 13-year-old girl unaware of how much joy she was about to take away from herself in the name of self-control. Whilst the weight I have gained in lockdown has been hard for me to emotionally reconcile, it has been a consequence of nothing but survival, and for that, I am trying to be grateful.

The simple things: wellbeing advice for the term ahead

New obesity measures: the overlooked impact on eating disorder sufferers

My bigger thighs come from Christmas nights sharing cheese and pickles with my dad, my change in dress size perhaps from the many evenings spent eating snacks and drinking wine with the company of friends over Zoom, the extra weight on my hips from aimless days stuck in my bedroom watching Netflix and enjoying some popcorn while the world outside my window collapses into fatal disarray.

Abundance is not a shameful thing, weight fluctuation is an inevitability of a well-lived life, and with each day I affirm these things to myself I get closer and closer to fully embracing the self that needs nobody’s acceptance but my own.

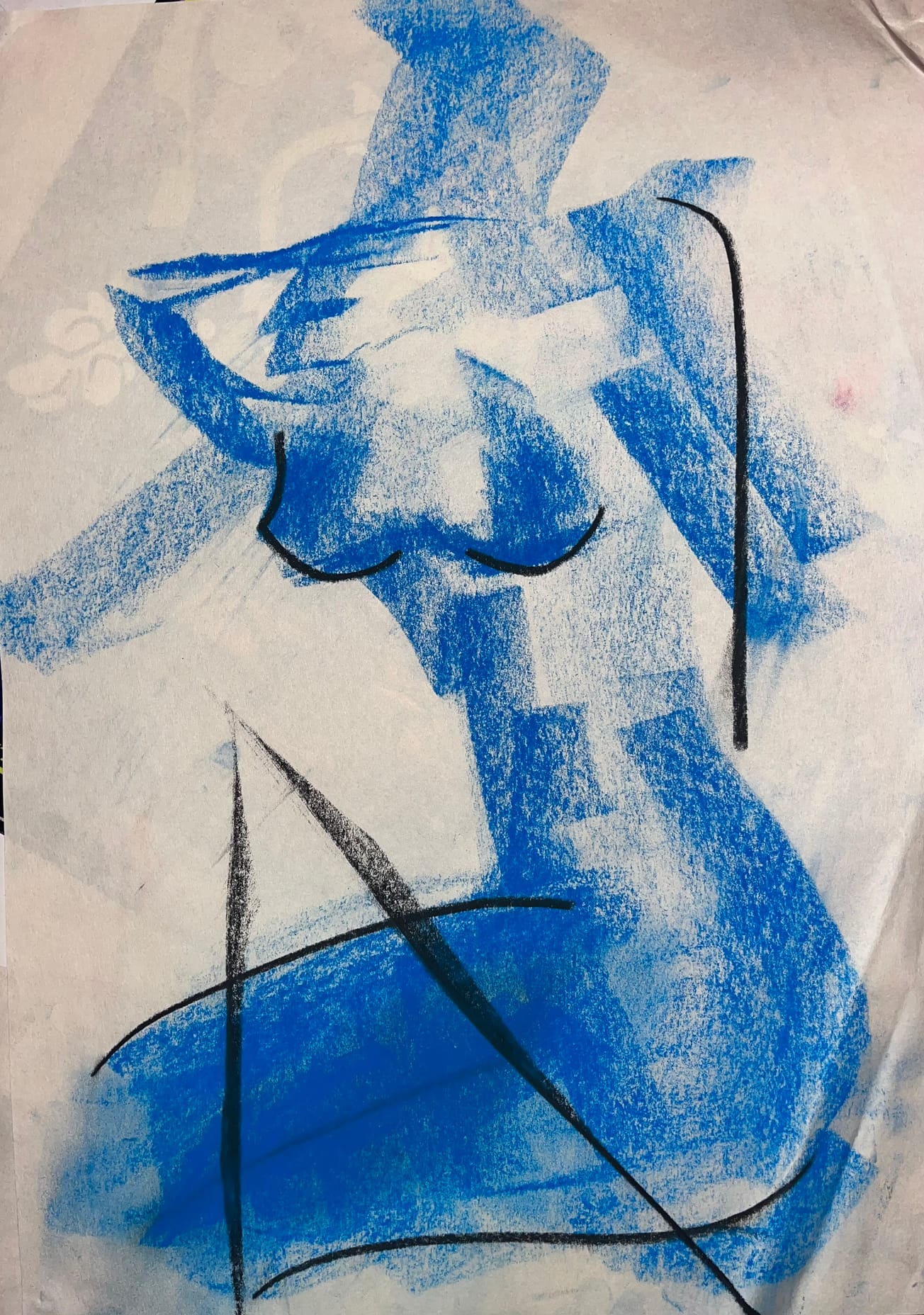

Featured image: Epigram / Ileana Mattea

If you or someone you know is struggling with an eating disorder, the following resources may be helpful:

Beat - The UK's Eating Disorder Charity / Helpline 0808 801 0677 / Studentline 0808 801 0811