By Megan Oberholzer, Fourth Year, Liberal Arts

On Saturday 15th November, the Afrika Eye Film Festival showed four incredibly powerful films at Bristol’s Arnolfini from all over the African continent, celebrating its 20th Anniversary. From Awam Amkpa’s complex Nigerian political drama, The Man Died (2024), to Aaron Kopp & Amanda Kopp’s hopeful animated story of a Swazi girl, written by the young children in a Swaziland orphanage, Liyana (2017), festival goers were not only left much to admire but also much to think about.

Upon arrival at 11:30, a short 15 minutes before doors were called, I met the excited self-described ‘super fans’ of the Afrika Eye Film Festival by the ticket stand, who told me many of them had been attending the event almost since it began in 2005. They intended to stay all day and by the evening, I waved many of them goodbye.

The Afrika Eye Film Festival director, Anne Menter told me between screenings, ‘I am delighted with the turnout for all the films today.’

She was especially excited for the screening of Ingrid Sinclair’s Flame (1998), which she hadn’t watched in 10-15 years. Even so, she stated, ‘The interesting thing is, all [of the films] have relevance today. You think the world has moved on, but we are still surrounded by war today. It’s the tragedy of humanity.’

The first screening was for Liyana (2017). Half documentary and half animated film, the story followed a group of children in the gorgeous Swaziland mountains as they built the titular character, Liyana, in class, decided her backstory and family, chartered her journey and her challenges, and plotted her happy ending, where together with her two younger twin brothers she made an orphan family of her own. Beautiful illustrations followed Liyana’s adventures across crocodile rivers, soft-sanded beaches, and treacherous caves harbouring angry beasts, while the voices of the children themselves narrated the story and provided the comedic moos of her Nguni bull companion.

The story took inspiration from the children’s own experiences and their journeys to the orphanage. The maturity of Liyana’s struggles reflected this, touching on the HIV pandemic, domestic violence, theft and kidnapping. But as the film drew to a close, the children turned to the camera; ‘Liyana was strong. I am strong.’ A young girl leaning by a tree declared, ‘I am going to write my own story with my own words. No one will tell me how it ends.’

The second screening was A Man Died (2024), debuting for the first time in Bristol. The film is based off a memoir of the same name by Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka and follows Soyinka’s imprisonment without trial during the rise of the Nigerian civil war. The audience learns of his activist past, watches his poor treatment behind bars and witnesses his growing determination to fight against political divides far greater than himself.

The film director, Awam Amkpa, dialled in over webcam for the Q&A hosted by Dr Samantha Iwowo directly after the film. Awam described his Bristol homecoming as ‘amazingly special’. He was in no way unfamiliar with the Arnolfini, where he used to ‘hang out’ and where he used to conduct his PhD interviews.

When asked about the themes of his film, Awam commented that he was fascinated by a civil war that ‘still animates Nigeria today.’ Awam pointed out that ‘the political rhetoric [of today’s Nigeria] is still influenced by ethnocentrism’, which still urges individuals to take sides. What is particularly interesting about Wole Soyinka, who as the credits rolled read a short excerpt of his writings, is that ‘he does not have fidelity to any party’ and is in many ways ‘a true post-colonial Nigerian.’

'[I was] deliberately playing an artistic game with documentary’ when staging his film. ‘I wanted to use history as a staging point to go into an artistic space. [And if there is] a pendulum between history and aesthetics - I favoured the aesthetic one.’

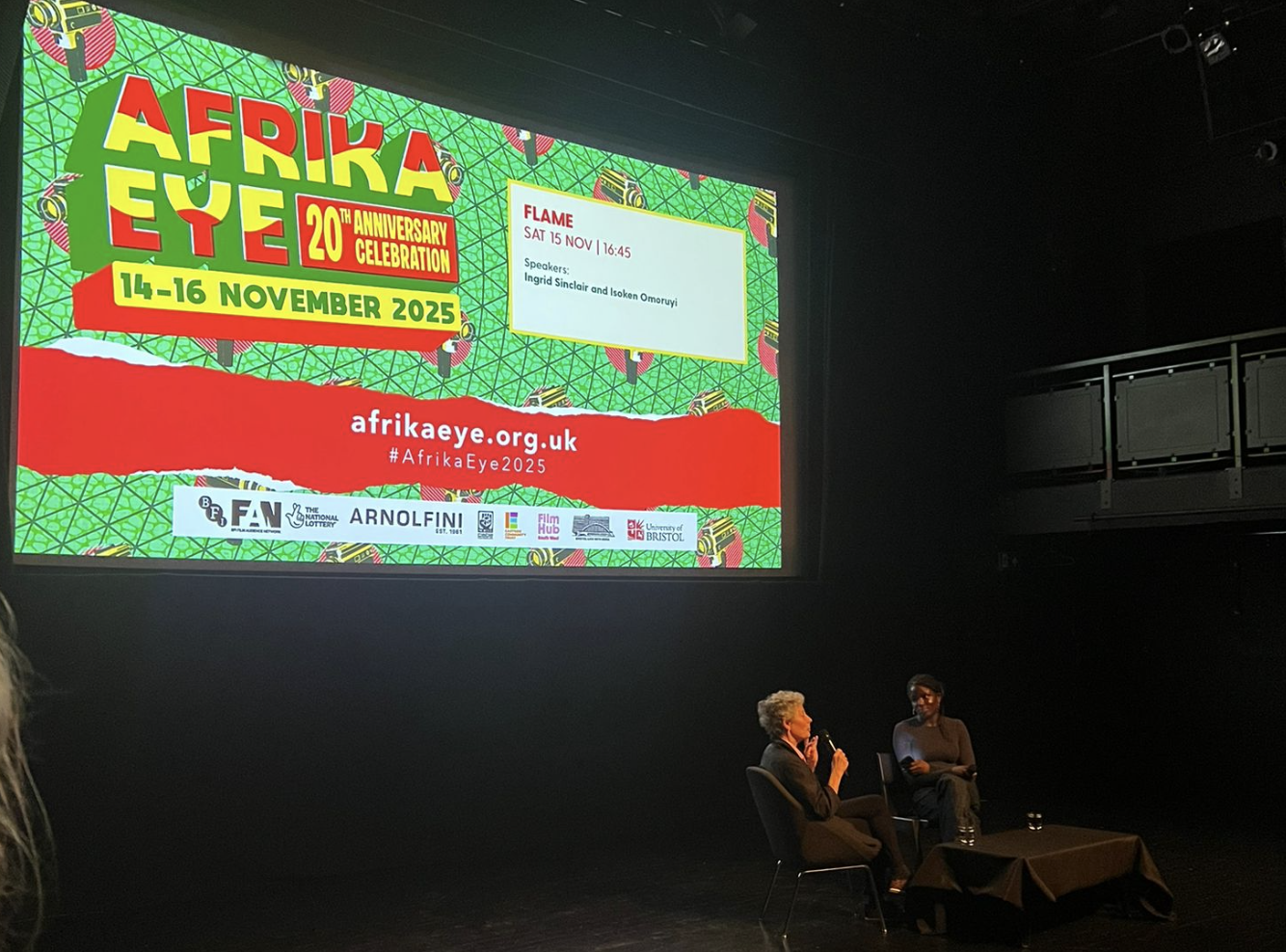

The third screening was the Afrika Eye Film Festival cofounder, Ingrid Sinclair’s Flame (1998). This story followed two friends Florence and Nyasha, as they join the partisan fight against former Rhodesia and now Zimbabwe’s white suppressors in the 1970s and what happened to them after.

In the following Q&A hosted by Isoken Omoruyi, Ingrid described the contrast between Florence and Nyasha as one between country women and modern women that intended to explore how women’s lives looked during independent Zimbabwe, immediately following the resistance. While Florence took on the new name of Flame and became a renowned fighter inspired by a real Zimbabwean woman who came to have over 400 soldiers under her command, Nyasha took on the name of Liberty and took advantage of the educational scholarships available through the resistance camps to lift herself out of poverty and into an affluent city life.

When asked what young audiences should take away from the film, Ingrid answered, ‘It’s a metaphor for struggle - for women everywhere. And I think that’s what women [continue to] respond to.’

Although the situation for women has evolved in Zimbabwe, Ingrid expressed there is still a lot of fighting to do.

The final screening was for the returning film, Félicité (2017) directed by Alain Gomis. The story is set in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, around a proud, free-willed singer called Félicité, whose life is turned upside down when her 14-year-old son is seriously injured in a motorcycle accident.

The determined but terrified mother races against time to raise the money needed for his surgery, resorting to chasing old debts, confronting her estranged ex husband and begging from the wealthy in their walled-off private homes. Life gets a little easier for her as she comes to trust and depend on an unlikely helper, a mechanic called Tabu, who originally dropped by to help fix her broken fridge. When he finally does fix the troublesome appliance, between all their challenges, the audience in the Arnolfini cheered and clapped, only to whine together as the fridge’s electrics took off like a washing machine.

Although Alain Gomis could not attend the planned Q&A, Ingrid stepped in to provide her thoughts. She pointed out the layered nature of the the film, which is a combination of a classical, realist story, a documentary of an orchestra - which provides much of the film’s soundtrack - and a dark and dreamlike decent into Félicité’s inner thoughts. ‘This is a story of an emotional journey that we can recognise from anywhere.’

Ingrid remarked, ‘it is funny, tense and tragic’ with ‘the biggest sense of place of any film I’ve watched.’ Alain’s Kinshasa city comes to life through an environment an audience member described as ‘a human circus contrasted with grace.’

As the first full day of the Afrika Eye Film Festival's anniversary weekend came to a close, many of the festival goers lingered in the cinema, chatting and laughing, sharing their responses to emotional moments and voicing their thoughts on the films.

As the festival director Anne said to me, ‘one of the reasons [the festival] exists is to bring in communities [...] and to open people's hearts and minds to the richness that comes from Africa.’

Featured Image: Epigram / Megan Oberholzer

This event was featured in the November edition of Epitome: Epigram's monthly go-to guide of unmissable events across Bristol. Sign up here to receive our curated newsletter in your inbox!

Did you manage to catch the Afrika Eye Film Festival at Arnolfini?