By Amelie Patel, Deputy Comment Editor

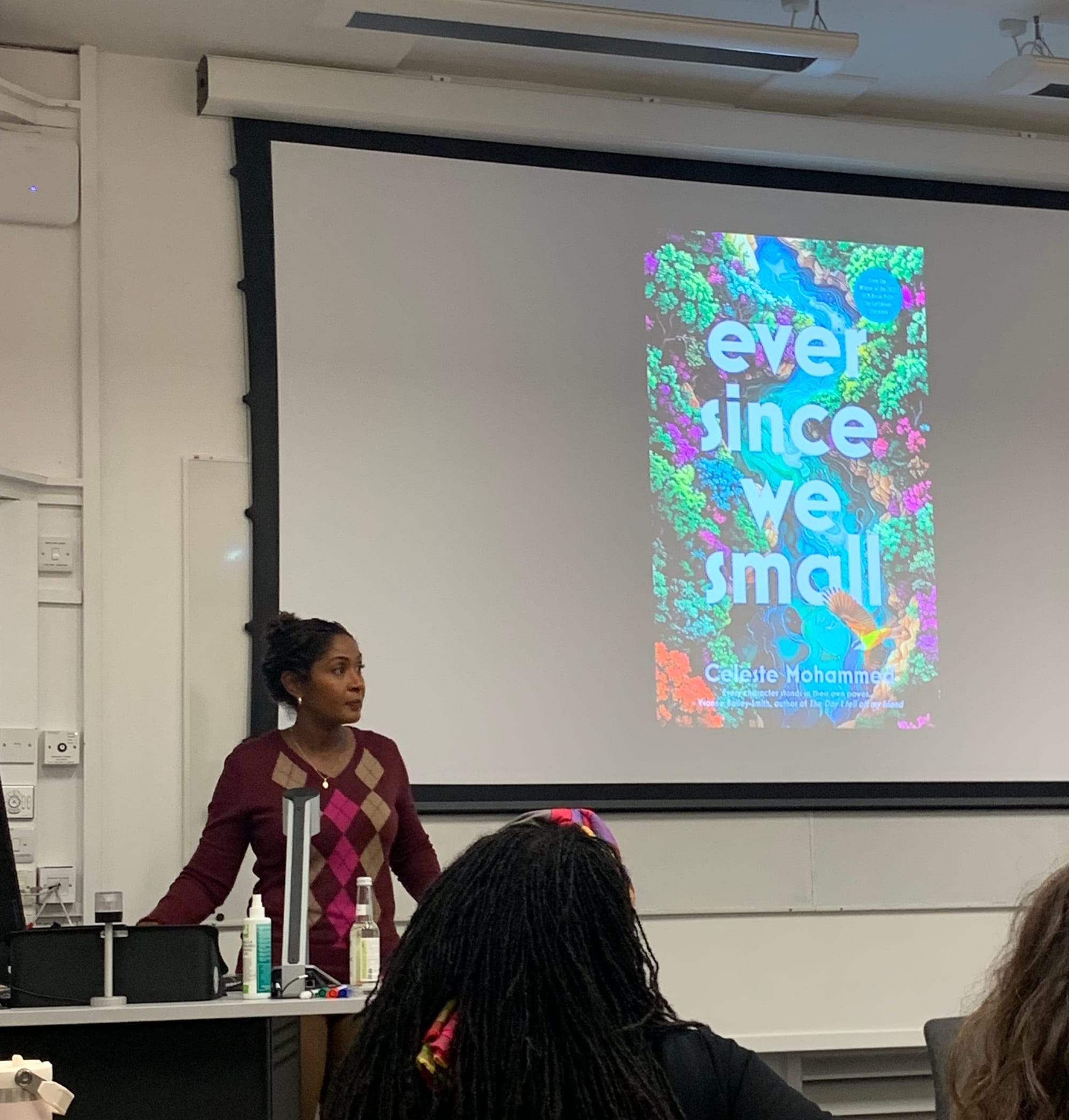

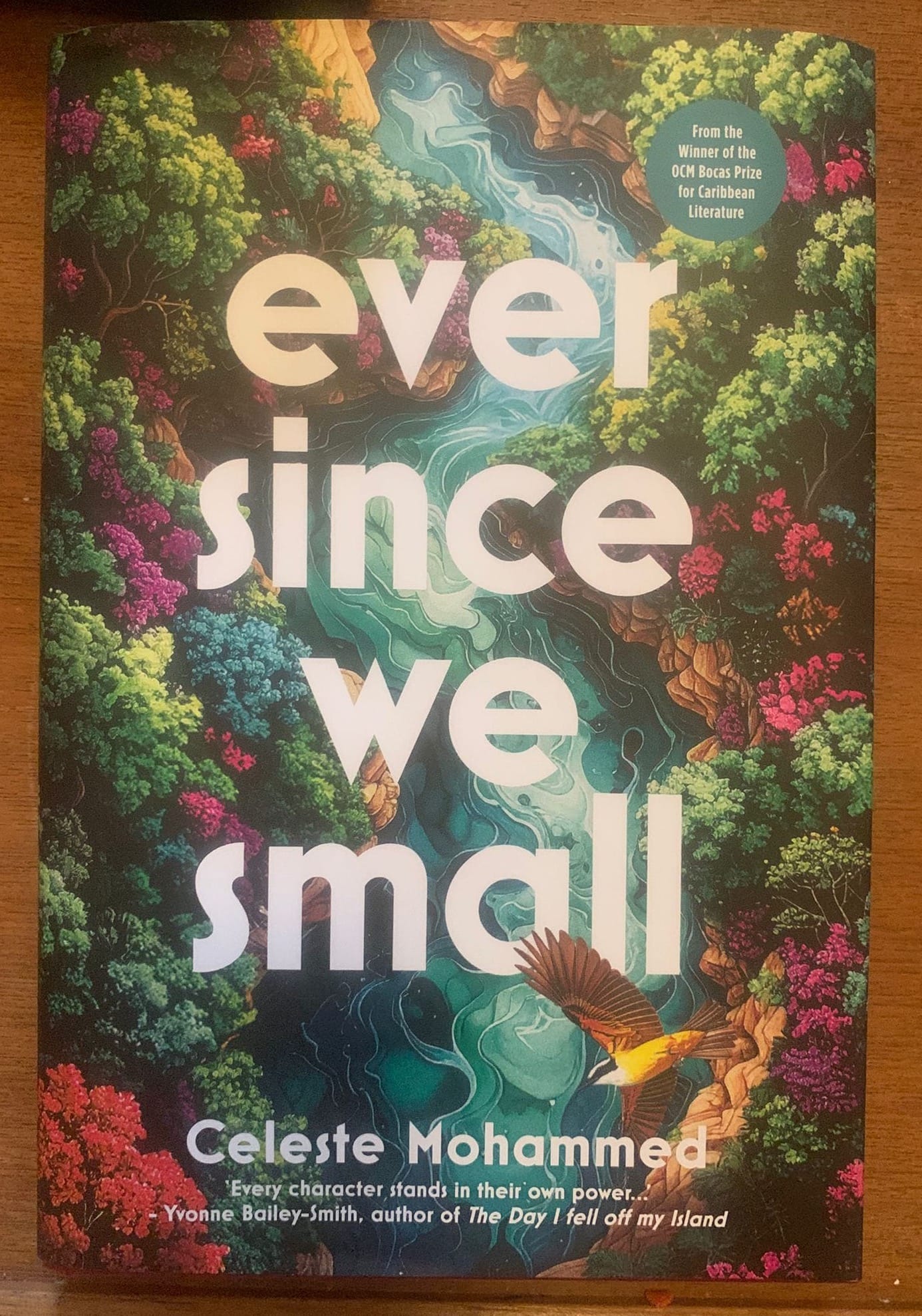

In honour of Celeste Mohammed’s new ‘novel-in-stories’ Ever Since We Small, I attended a reading group led by Mohammed and later conversation between Mohammed and A.J. Donnell. Celeste Mohammed was launched into literary fame with the release of her debut novel Pleasant View, which scooped the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature in 2022. Ever Since We Small is her third novel.

The event was run by Bristol’s Caribbean Studies Studio, an initiative formed last year as part of Bristol’s Reparative Futures Programme , which aims, ‘through a series of targeted initiatives, to redress some of the systemic injustices arising from the African chattel enslavement’. The Caribbean Studies Studio is 'a community of scholars, writers, scientists and creative practitioners whose work spans the greater Caribbean and its diasporas'. Importantly, Ever Since We Small was released first in the Caribbean in May, a deliberate choice to put Caribbean consumers first in a novel all about their lives.

Before writing I ‘had not comprehended that this history was happening day to day in my home town’.

Ever Since We Small was a gripping read. I was struck by its intelligent weaving of a multi-generational tale; beginning in colonial India and following the fictional Jayanti's travels to the Caribbean as an indentured labourer, and settling in Trinidad as the battleground for posterity to reckon with their roots. It lends incredible humanity to tough topics, including femicide and rape. With it's tracking of multiple stories, as a reader I was wondered how all the threads would be satisfyingly collected at the end of the novel. The ending did not disappoint, in fact it was both moving and masterful.

At the reading group, a small group of students and staff were present to pick Celeste’s brain on the novel. When Celeste was asked about her choice of topics, she said that before writing she ‘had not comprehended that this history was happening day to day in my home town’. Fiction is the only thing that can ‘get in the minds of these people who were indentured on the ship’ which Jayanti sails on from India to Trinidad.

‘Oral storytelling is part of a rich, archaic tradition in indigenous societies, so the form feels natural’

Technically, the book is a ‘novel in stories’. I asked why she chose to write in this form over traditional long-form narrative. Her response was fruitful. For one, oral storytelling is part of a rich, archaic tradition in indigenous societies, so the form feels natural. Secondly, it resists western expectations of form, proving that the novel’s effects can be achieved in an alternative form. Finally, there’s something satisfying about using the form which out of necessity Caribbean writers were forced to write in until the 1960s, with publishers few and far excepting only short submissions. With these reasons in mind, the novel-in-stories form starts to make a lot of sense. However, she did say she was not opposed to writing a conventional novel, in fact she is excitingly working on one right now!

A foundational facet of the book is its use of various forms of creole. Creole is ‘a type of language developed from a mixture of different languages...now spoken by a group of people as their first language’. Don’t let this put you off. As a reader new to creole, its rhythms take only a moment to adjust to and lead to a rich and unique reading experience (especially if the book is read aloud as Mohammed hopes). Further, she said that ‘I don’t believe that you have to understand every word in order to understand the story’. Different types of creole are used in each story, showcasing the diversity of creole, and importantly documenting some of its forms that ‘will soon be dead’. In the titular story Ever Since We Small, one of these endangered forms is used: Indo-Trinidadian creole.

As for building character, she said ‘I have to embody and become that person. It helps that I was a lawyer - guilty or innocent I have to advocate for you’.

Mohammed does not write her stories in a strict order. Such is the illusion of the writer’s process that they sit by candlelight following a burst of inspiration, churning out their entire manuscript over a series of midnights. She wrote them over a long period of time, halfway through realising she had enough fragments to make up a novel. In fact, the first letter was written last, in order to collect the stories to an origin point, and the last chapter was originally written in meta-fiction style, until her publisher got back to her and told her to write it in prose. Clearly, writing is an experimental process and negotiation to find the most effective way to tell a story. Mohammed also stressed that writing is a research-intensive process for her. Each line is meticulously thought out and strictly informed by real histories. When asked about her perceived reader, she said that she always wants to write with Caribbean people as her first audience. ‘They keep me honest, they can smell bullshit’, she said to much laughter. As for building character, she said ‘I have to embody and become that person. It helps that I was a lawyer - guilty or innocent I have to advocate for you’. This is what makes her storytelling so brave.

Having spent some time in Celeste’s presence, I was also left slightly in awe of her. The wisdom and compassion with which she conducts herself is one of a generational talent.

If you're still reading here’s a fun fact - Mohammed originally called the novel Gopaul’s Luck!

Featured Image: Epigram/ Amelie Patel

Will you read Ever Since We Small?