By Eleanor Bate, Deputy Film and TV Editor and Lilja Nassar, Comment Subeditor

As I made my way through Bristol’s evening bustle, and its inevitable downpour, towards 1532 Theatre, an independent performing arts centre tucked just off Clifton’s iconic Park Street, I felt a quiet excitement for what the evening would bring. The venue, small but spirited, buzzed with energy as students, families, and journalists alike, gathered out of a shared reverence for Sir David Attenborough and his tireless advocacy for the future of our planet.

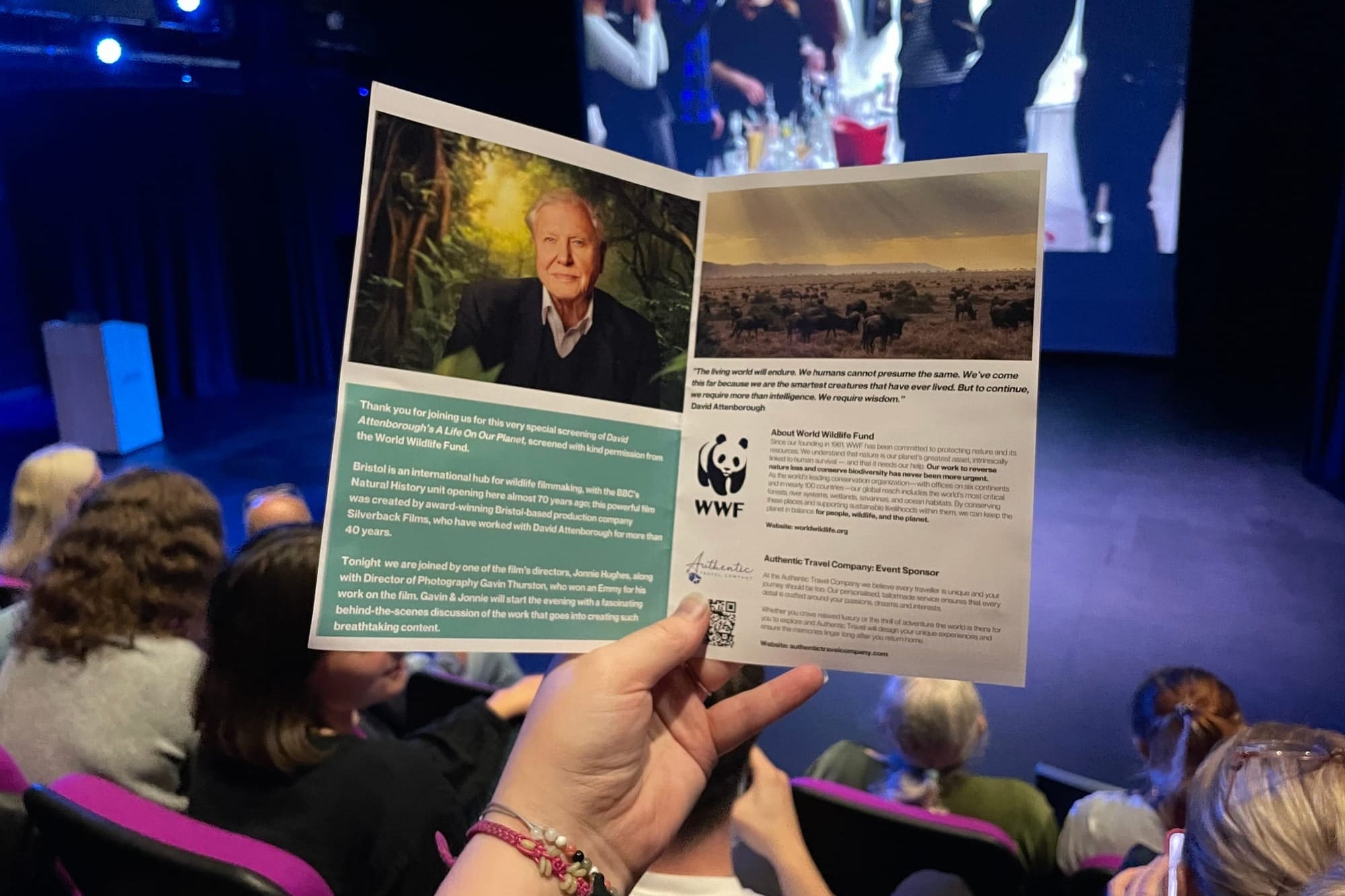

Hosted by Bristol Film Festival, the screening promised not just a cinematic experience, but an important conversation, joined by a couple of the brilliant minds behind the feature, one of the film's Director's, Jonnie Hughes, and Director of Photography, Gavin Thurston.

The event also carried a sense of immense pride for our city. Unbeknownst to many, Bristol plays a significant role in wildlife filmmaking. Local production company Silverback Films, dedicated exclusively to creating films that confront our environmental crises, are renowned for pairing powerful storytelling with breath-taking cinematography. Knowing that A Life on Our Planet (2020) was produced on our very doorstep gave the evening an added intimacy, a reminder that Bristol is helping shape the fight against climate change.

Silverback’s impact is undeniable: their recent release Ocean 2025 smashed box office records, opening to £573,551 at the UK and Irish box office, the highest-grossing debut for a nature documentary on record. And based not only on their impressive list of accolades but also on my own experience watching this documentary, it’s safe to say they truly delivered.

An Intimate Introduction

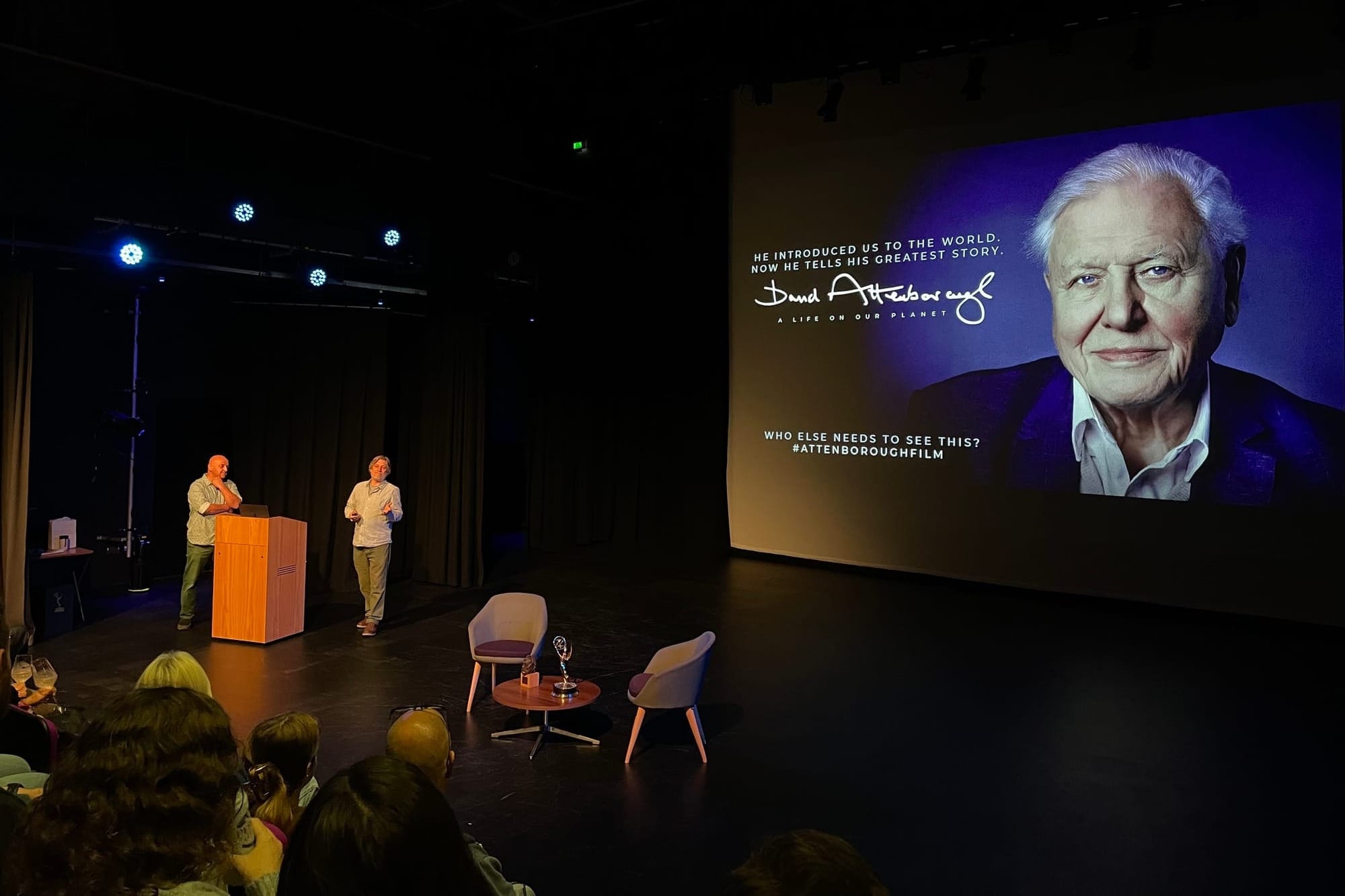

After some light schmoozing, it was time to step into the theatre and take our seats for an intimate screening of around 300 attendees. A short introduction from a Bristol Film Festival host gave way to a presentation by Hughes and Thurston, offering the audience a glimpse into the filmmaking process behind this award-winning documentary. They clicked through slides showcasing cutting-edge technology, candid on-set moments with Attenborough at his childhood home in Leicester, where his passion for geology first took root, and insights into a scripting process that constantly adapted to the ever-unfolding climate crisis. With a grin, they admitted to briefly outpacing Christopher Nolan’s Tenet at the box office on opening day, a short-lived victory, perhaps, but an impressive one all the same.

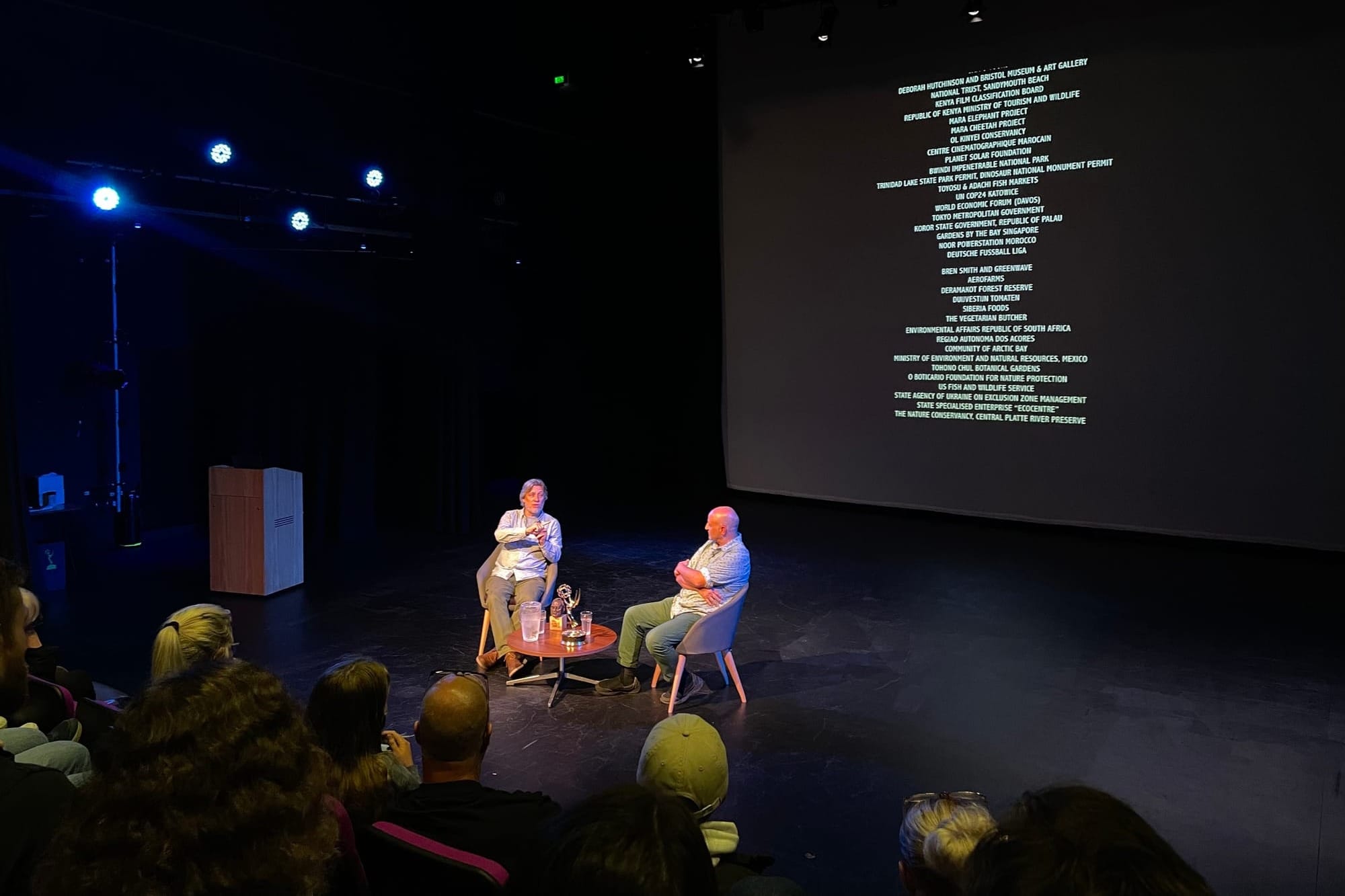

Their work took them across a range of striking locations, from Kenya to Tokyo, Colorado to Ukraine (one of the few countries Attenborough had never visited, and which Hughes noted they had the privilege of introducing him to). Thurston, who went on to win an Emmy for his cinematography on the film, mentioned almost in passing a comment that has lingered with me ever since: his experience filming, and the things he bore witness to, led him to adopt a vegan diet — a commitment he has maintained in the five years since the documentary’s release. It is hard to fathom the scale of horrors one must encounter to overturn nearly fifty years of meat eating. That personal shift speaks volumes about the significance of this documentary, and why screenings like this remain so vital.

On Screen: A Life on Our Planet

Climate change, as narrated by a man nearing 100, is not a perspective you encounter every day. A film beginning with an introduction as succinct as 'I am David Attenborough, and I am 93' is just ominous enough to immediately draw its audience’s attention to an impending doom. Attenborough has lived through all the flashing, frightening statistics dispersed throughout the film, biodiversity levels plummeting as the years climb higher. We are shown that, though devastating to confront, it is far more distressing to witness our own impact on the environment. It’s as if we’ve forgotten that it is not some immaterial force looming above us and dominating newspaper headlines, but the very thing that sustains us.

What struck me most about this film, particularly coming from Attenborough, is its inclusion of archived footage. Seeing his lifelong dedication to the environment unfold across decades evokes a deep sense of shame, but a productive kind. It’s the sort of shame that inspires you to act, to contribute even a fraction of his tireless effort to preserve our planet.

While I can find fault in the film’s seeming neglect of the economic and political decisions largely beyond the layperson’s control in halting climate change, there is something quietly moving about its focus on the individual agency we all possess. It reminds us that change begins with awareness, and with the choices we make every day.

I cannot call the film’s chronology 'uplifting' per se, despite its breath-taking natural imagery. What sets A Life on Our Planet apart from Attenborough’s previous work is its grave tone and its unflinching framing of our natural world. At times so bleak it borders on psychological horror, it is never merely disturbing or forgettable — instead, it becomes something hauntingly memorable.

Life on Our Planet is, in equal measure, tragic and hopeful. While Attenborough and his team confront us with a sobering reality, accompanied by stunning cinematography, devastating natural beauty, and his authentic narration, they manage to strike a delicate balance between despair and determination. It is not all doom and gloom, but it is honest, urgent, and deeply poignant.

If I could recommend just one documentary for everyone on Earth to watch, it would be this one. It has been masterfully assembled in such a way that it cannot help but move even the most resistant of viewers. Director Jonnie Hughes shared that they’ve screened the film to rooms full of businessmen and the like, people who, in no small part, contribute to the very crises the film confronts, and watched as they, too, were changed by what they saw. That, if nothing else, is proof of its power.

Questions & Answers with Hughes and Thurston

If I hadn’t drawn enough impact from the film itself, the fascinating Q&A session that followed certainly cemented its importance. The sheer effort behind the production reflected both its significance and Attenborough’s passion for communicating the degradation of our planet — or rather, our degradation of it. Attenborough used an autocue while presenting the script; however, his animated and theatrical gestures, endearing proof of his lifelong enthusiasm, complicated the device’s effectiveness. The camera crew, however, devised a unique technique that allowed him to maintain steady eye contact with the camera while preserving his distinctive presentation style. The production team’s big Hollywood moves, achieved without a big Hollywood budget, were appropriately acclaimed, and the film stands as one of the most impactful I’ve seen to date.

Attenborough’s influence has been far-reaching. In the wake of his newest release, Ocean, the heads of Greenpeace UK, Oceana UK, and the Blue Marine Foundation have written to Sir Keir Starmer, urging him to prioritise ratifying the Global Ocean Treaty — an initiative to conserve the high seas and protect 30% of the world’s oceans. If more people had access to A Life on Our Planet (released, unfortunately, at an inconvenient time) and found the incentive to watch it, the environmental reforms that follow could be even more significant, offering greater benefits to our planet. The film was Attenborough’s witness statement, and I believe it.

From Screen to Reality: What We Can Do

We are not entirely helpless as individuals, you’ll be pleased to hear. The world we want remains within our reach, and there are tangible ways we can accelerate our transition towards it. As Attenborough reminds us, the solutions are already within our grasp, we simply have to commit to them. He advocates for re-wilding our planet: restoring natural habitats and allowing the space to heal. He also highlights that bringing countries out of poverty, providing universal healthcare, and improving girls’ education would help stabilise the growing human population sooner and at a lower level. Renewable energy, solar, wind, water and geothermal, could sustainably power all human activity, while protecting even a third of our coastal areas from fishing could help fish populations recover, leaving the remaining areas sufficient for human consumption.

And of course, change begins with what we put on our plates. Humans shifting their diets to reduce (or eliminate) meat in favour of plant-based foods could allow land to be used far more efficiently. Whilst veganism may seem daunting to many, even small, collective efforts can make a big difference. Start with something simple, like Meatless Mondays. If you need a little push to take that first step, I highly recommend watching A Life on Our Planet. Its tragically beautiful first-hand account of our planet’s slow decline serves as powerful motivation for its preservation.

I know, the news can seem dreary, and climate recovery often feels like an impossible feat. With billionaires taking ten-minute flights on private jets and corporations profiting from the environment’s decline, it’s easy to feel helpless. After all, what difference can one person make? Yet that very thought process is our downfall. If we all vow to make small changes, in our diets, in how we travel, in the way we think about consumption, we can and will see an impact.

I found myself inspired not only by what Attenborough and his team showed us, but also by the changes Director of Photography Gavin Thurston has made in his own life. I’ve begun eating meat-free from Monday to Friday each week. I’m not here to preach, but by eating vegetarian five days a week, I’ll be saving around 2796 bathtubs of water and avoiding roughly 1007 miles of greenhouse gases per year, a small choice, but a meaningful one.

The Earth will continue with or without us; if we want to live on with it, we must learn to live for it. What Attenborough shows us is not simply a call to action, but a call to connection — a reminder that our smallest choices still tether us to something much larger. His message isn’t one of despair, but of responsibility, and of love. Because if we still care enough to change, then maybe there is time still for humanity.

Featured Image: Epigram / Eleanor Bate

Will you vow to reduce your carbon footprint, or remain a bystander to our planet’s decline?