By Hannah Cahill, Fourth Year Biochemistry

Recent research has revealed that our microbiome may influence our mental health, providing a new route for mental health treatments.

The human body is home to over 100 trillion bacteria, good and bad, collectively termed the microbiome. While this has been recognized for decades, over the past 10 years our understanding of the microbiome has grown, and we are beginning to realise its profound impact on human health; scientists are even beginning to refer to it as a distinct organ.

Photo by Sanofi Pasteur/Flickr

A healthy balance of good and bad bacteria in our gut is essential for normal bodily functions, however this can be disrupted by antibiotic use, early life infections and diet, among many other things. While it is unsurprising that the composition of your microbiota has shown strong links to gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances, obesity and inflammation, there is an emerging consensus that our microbiome could be playing a role in our mental health too.

95% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the glands of the gut.

The gut-brain axis refers to the communication between the brain, the cells lining the gut, and the microbiome inside the gut. Through hormonal, neuronal and immuno-signalling, these three distinct cell types can regulate and interact with each other. The brain controls the guts movements and secretion of various hormones – some of which have been found to effect microbial gene expression. Meanwhile, the microbiota can communicate to the brain by producing or contributing to the production of the neurotransmitter’s serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine. It may be surprising that these household name neurochemicals are in our gut too, but in fact 95% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the glands of the gut. Studies of germ-free mice found that they had less than half the serotonin levels of normal controls, indicating the microbiome was contributing to its normal production.

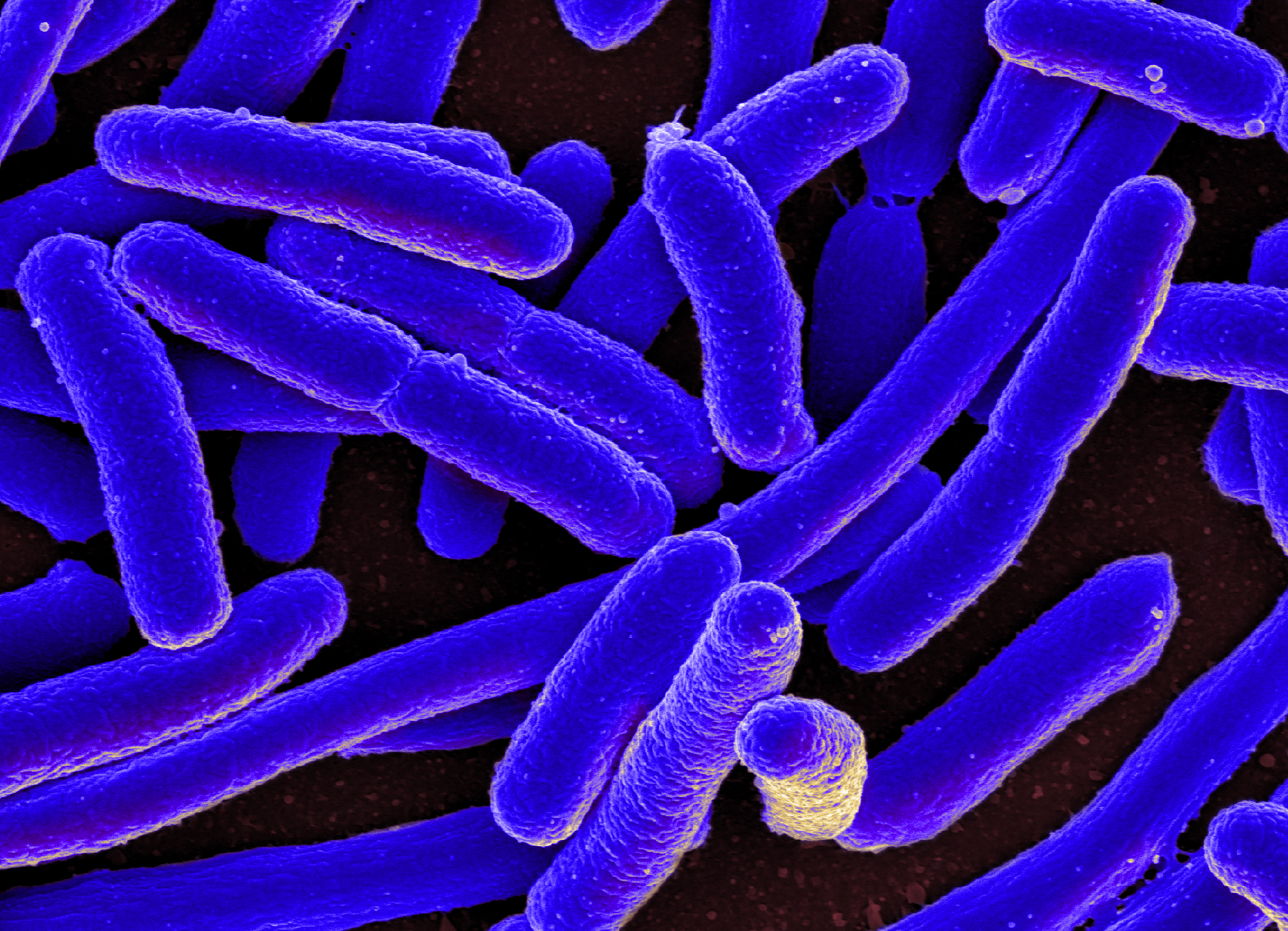

Germ-free animal studies have been a useful tool in understanding the effects of the microbiome. It was the finding that germ-free mice had an increased stress response that initiated research into links between the microbiome and mental health. This high-stress state could be reversed by colonising the mouse’s gut with normal microbiota, indicating the lack of germs was to blame. These mice had reduced synaptic plasticity – the proposed mechanism of learning and memory. Additionally, studies using probiotics (supplements containing beneficial bacteria) found they reduced anxiety- and OCD-like behaviour in mice.

Photo by NIAID/Flickr

More recently, human studies have presented promising results too. Many human psychiatric and neurological disorders occur alongside GI dysfunction. While it was thought that the microbiome was playing a role in these GI disturbances, it’s now proposed that they are contributing to the primary disorder too. A study using probiotics containing Bifidobacterium longum found that human subjects had reduced responses to negative stimuli and a lower depression score than the placebo control group. This probiotic has also been shown to reduce reports of sadness and aggressive thoughts. Out of the clinic, E. coli outbreaks in Germany and Canada correlated to increased anxiety and depression in the affected populations, indicating the imbalance of gut microbiota caused by the infections could be contributing to these mood disorders.

...after ‘doping’ herself with an elite cyclists’ faecal sample, her athleticism improved markedly.

While it may be unnerving to think of the organisms living in your gut being able to control your brain, it’s important not to get scared. Having a healthy relationship with our microbiome is the best way to prevent an attack from within. Probiotics and prebiotics (supplements containing food for beneficial bacteria) have shown promise in maintaining a healthy microbiota balance. And while it is unlikely that these supplements will replace current treatments for mood disorders like anxiety and depression, it may be that they could complement therapeutics to improve their efficacy. Perhaps most beneficial, especially for the general population, is a balanced diet rich in probiotic fermented foods and prebiotic high-fibre foods, however for those less squeamish, there is an emerging trend of faecal transplants to improve your microbiome composition.

Yep, you heard right. Faecal transplants. One microbiologist researching cyclists stool samples claims that after ‘doping’ herself with an elite cyclists’ faecal sample, her athleticism improved markedly. Given how little we really understand about our microbiome, this is definitely not recommended practice, however some pharmaceutical companies are looking into developing ‘artificial poop’ to circumvent the current safety issues. Watch this space…

The past decade has shone a light on this hugely important new organ we have all been obliviously harbouring; now the focus is on truly understanding it. The Human Microbiome Project was launched in 2008, aiming to provide genomic and metabolic data of our complete microbiome. Like the Human Genome Project, it is likely that this will provide more questions than answers, however understanding of our microbiome may be of greater use as, unlike our genes, it is easily modifiable. With more understanding of the intimate links between our microbiome and mental health we may be able to improve the often-inadequate treatments of these complex disorders.

Featured Image: Flickr / AJC1