By Henry Griffiths, Third year, Philosophy

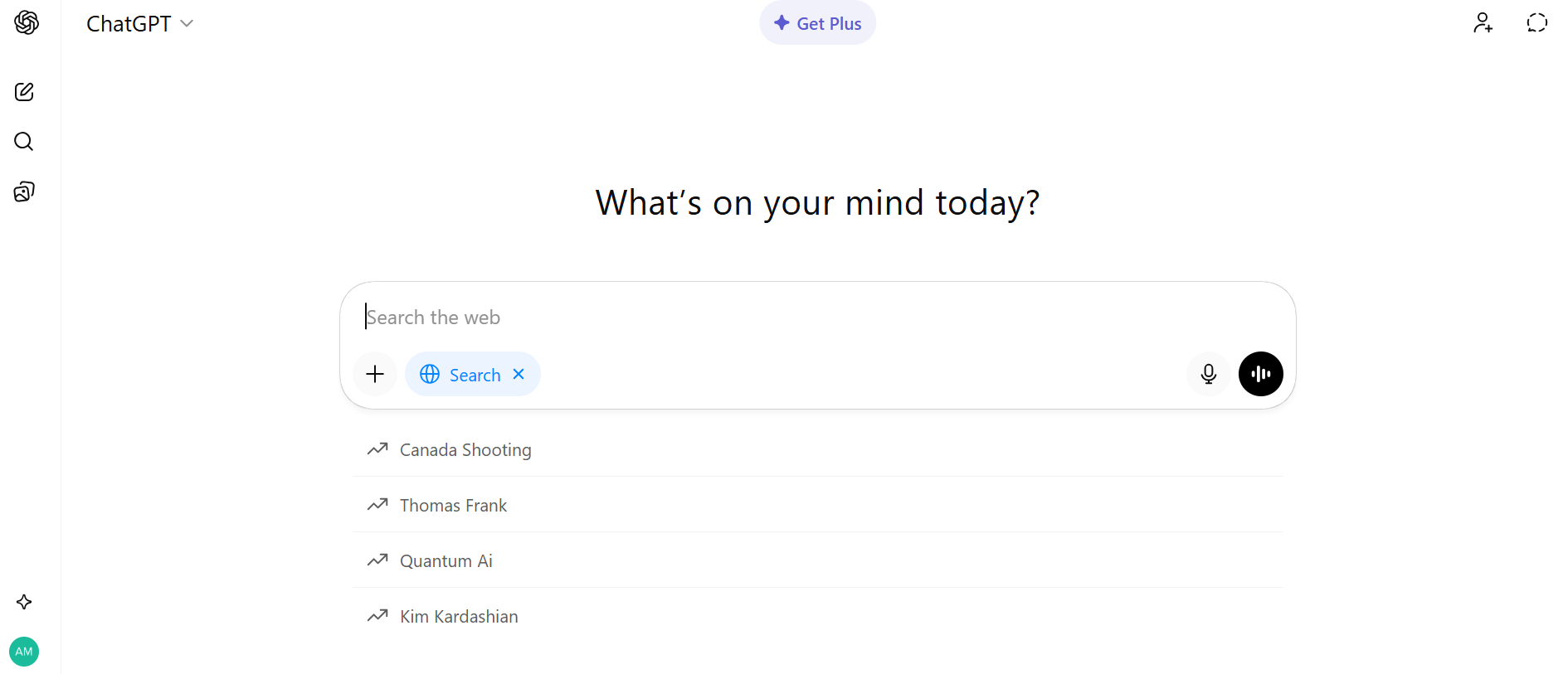

AI has swiftly invaded the academic landscape: a 2025 survey of 1,000 students found that 92 per cent now use it, an explosive increase from the 66 per cent reported in 2024. Here at the University of Bristol, you only need to enter a library to feel this change. A brief scan around the ASS showed that about half of laptops had ChatGPT running at any given time. This reality is not necessarily a bad one; AI can make the compiling and structuring of information incredibly efficient. My concern is when it is overused in a careful, disguised manner.

Students often use AI to supplement their learning, utilising a digital assistant to help find resources and break down key information. Occasionally, you may also hear stories of students submitting an essay entirely devised by such software, even forgetting to delete the ‘certainly, here is an essay that…’ part of their copied-and-pasted submission. However, the real problem concerns what might be deemed the ‘smart cheater’: the student who directs AI to create nuanced, striking phrases or paragraphs that they couldn’t have produced themselves, on topics they haven’t fully researched. If undetected, this completely redefines the playing field, one in which academic merit can be based not on engagement with one’s degree but on the clever use of technology.

The effects of this are twofold. First, it undermines the purpose of academic institutions. University is a place to develop critical skills and a space to exercise and cultivate free thought. The overuse of AI subverts these principles, mechanically feeding the student information not only in the form of content, but also of syntax, structure and form. As familiarity with receiving instant feedback grows, the will to engage in independent analysis and reflection will surely diminish.

Second, it disadvantages the honest writer: the student who is engrossed in their subject, producing rigorous assessment and analysis that is authentically their own. This is a real concern for students – the methods of the clever cheater are quicker, easier and, sometimes, can yield better results. Speaking to a History Undergraduate, she reflected on the feeling that ‘doing the right thing puts me at a disadvantage’. AI can highlight subtle, complex avenues of argument, thus conflating grades and making the honest writer’s thoughtful thesis appear not as rare or impressive.

The traditional methods of essay-writing can be time-consuming to the point of being laborious, and plugging prompts into an AI can seem like an effective fix. Aware of the smart cheaters out there, it may feel futile to engage with these traditional methods. Furthermore, it may undermine the value of a great argument. Though, I should be careful not to glorify AI too much as it can be a fallible, misleading resource. ChatGPT can fabricate facts, point you to a quote that doesn’t exist, and confidently offer a line of argument that is unequivocally incorrect. Language models communicate with such a fluency and authority that it is easy to take their responses as true.

‘How would you know if this very article had not relied extensively on AI? That would be a great irony.’

The AI issue dissolves only if we can be confident about the methods in place to delineate this difference, but at present we simply can’t be. AI detectors are hardly reliable, sometimes even producing false positives that create a culture of ‘guilty’ until proven innocent. The market-leading AI detector Turnitin, employed by the University of Bristol and many other universities, claims to have a false positive rate of <1 per cent, although it is hard for students and educators to know whether this is true. The Washington Post for example found that this number may be closer to 50 per cent - a staggering difference. This may not be surprising: how would you know if this very article had not relied extensively on AI? That would be a great irony.

I am currently taking three modules, each of which requires an end-of-term essay worth 80 per cent of that unit testing similar skills of critical analysis and original thought. Yet their guidance on the use of AI varies considerably: one allows minimal use (for spelling and grammar), another offers no guidance at all, whilst the third prohibits AI completely – even for research. To me, this inconsistency reflects a broader struggle: universities struggling to adapt to this new technology and unable to put a cohesive set of rules in place.

So what should be done? Universities should strive to standardise their AI policy within subjects or faculties so that students can be confident in how they are being assessed and lecturers can mark consistently. The challenge is that essays, presentations and reports within subjects may warrant different procedures, whilst AI models are changing and improving at a rapid pace. Until AI detectors and university assessors catch up to the challenges AI presents (if they can), we should implore students to use this new technology in a fair and balanced way: to supplement their learning rather than replace it.

Featured image: Epigram / Hanno Sie

Do you think students have a responsibility to use AI discriminately?