By Milan Perera, Arts Critic Columnist

Epigram has pored over numerous reports to assess the long-held claim that the University of Bristol has a reputation of elitism, social exclusion, and an entrenched ‘drug culture’ amongst its students. Is this the case, or are such notions simply a sustained, unfounded stereotype perpetuated by its detractors?

It goes without saying that the University of Bristol has a reputation as a shining beacon of scholarship and innovation in the West of England and beyond. The Graduate Market Survey for 2021-2022 ranks Bristol at number three in terms of universities targeted by top employers, faring better than Russell Group peers such as Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham. In the latest Research Excellence Framework (REF), the University of Bristol ranked fifth for research in the UK, with an astonishing 94 per cent of its research assessed as ‘ground-breaking’. A shining beacon perhaps, but for whom?

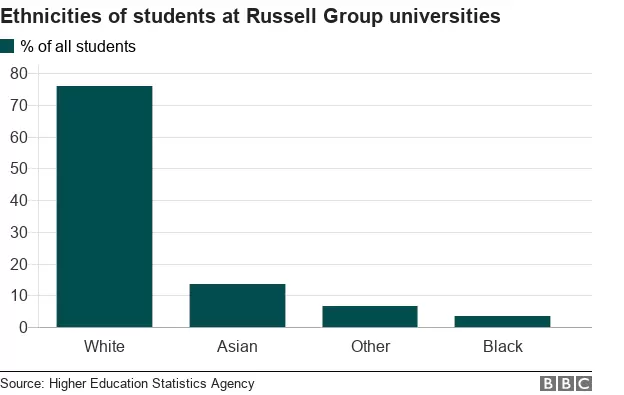

It’s no secret that the University of Bristol has historically held a reputation for lacking ethnic diversity. When Epigram analysed the national statistics on the representation of ethnic minorities at both Russell Group status and non-Russell Group status universities, the findings were nothing short of a revelation. In 2021, the percentage of ethnic minorities in the UK sat at 14 per cent. According to a BBC compiled report in 2018, the percentage of ethnic minority students at non-Russell Group universities was eight per cent, while the intake of ethnic minority students at Russell Group universities was just four per cent.

The statistics were not evenly spread among the Russell Group universities either. According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) in 2016, at the University of Cambridge the percentage of students who identified as black was a mere 1.9 per cent, while at Oxford this figure was even lower at 1.2 per cent. In the same year at the University of Bristol, the percentage of ethnic minority home undergraduates was 14.5 per cent. This promising trend continued until 2021, and this figure currently stands at 19.5 per cent.

But this could be a misleading representation of the data. The evidence suggests that the University of Bristol set the benchmark higher than its Oxbridge rivals by a comfortable margin, but how do these figures stack up against metropolitan Russell Group institutes such as the University College London (UCL) or Queen Mary University London (QMUL)? Like the city of Bristol, London is a vibrant hub of different ethnic groups which boasts a rich diversity. So much so that the percentage of ethnic minority students at UCL is reportedly 18 per cent, while at QMUL this figure stands at 65 per cent. In comparison, Bristol’s minority representation record has further to go before it can be considered a progressive institution.

A consideration of Bristol’s bad press would hardly be complete without an investigation into its purported lack of social inclusion and accusations of classism. Does this reputation stand up to the scrutiny of statistics?

The national percentage of secondary school students that attend fee-paying public schools stands at seven per cent—a figure that pales in comparison to the 24.5 per cent that are currently privately educated at Bristol.

There is a widely held belief that Britain’s flourishing private school sector hones its students to be ‘university material’—a claim seemingly supported by evidence, as The Sutton Trust’s ‘Access to Advantage’ report found that independent school pupils are over twice as likely to take a place at Russell Group institutions compared to those in non-selective state schools, and even schools with similar exam results had very different rates of progression to top universities. James Fishwick, Secretary of the 93% Club, has previously articulated the view that the University of Bristol has an issue surrounding social inclusion in various student publications. He proposed a seven per cent cap for private school entries, which was subsequently rejected. In an interview with Varsity, Fishwick reiterated that despite the motion being drowned out, it ‘achieved creating a greater dialogue about how to deal with the inequalities—not just state versus private, but getting into the power and privilege that private education affords’. According to The Times inclusion rankings in 2020, Bristol ranked 113 out of 116 universities. This is an eye-watering statistic.

While the University of Bristol may have considerable grounds to make in terms of improving its social inclusion record, there are few complaints among the small businesses in Bristol regarding the spending power of its students. The array of pubs, nightclubs, cafes, rental apartments and independent shops dotted around the city warmly welcomes the substantial monetary boost brought by its 20,000-strong student body. Speaking to Epigram, the ever-welcoming landlord of The White Bear Craig Hutcheon commented that ‘It’s impossible to think of Bristol without its students’.

Another contentious claim often levelled against students of the University of Bristol is a reputation for drug abuse. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction has named the city of Bristol the cocaine capital of Europe. An anonymous Epigram survey of nearly 300 students found that 77 per cent of Bristol students have taken illegal drugs for recreational purposes and that 89 per cent of those who took drugs did so whilst attending the University. The survey also revealed that 26 per cent of students had felt pressured into taking drugs.

When Epigram interviewed a consultant psychiatrist who works closely with students on narcotics abuse, they admitted that ‘Sadly there is a drug culture among the university students in the region. Most of them have the means to afford that sort of lifestyle’. The little-known movie Starter for 10 (2006) charts the highs and lows of a white working-class teenager at the University of Bristol as he adapts to the fads of his privileged peers. In one scene the main character, played by James McEvoy, tentatively smokes cannabis not to be branded a ‘village bumpkin’ by a classmate whom he is trying desperately to impress.

A Mail Online national survey asking students at UK universities whether they had taken illegal drugs listed the University of Bristol at eighth place. The city’s colourful nightlife is often highlighted as a contributing factor to the drug culture amongst its student population. It is not entirely unheard of that recreational drugs are distributed not only in nightclubs but also at private parties attended by students. The University has expanded its support network in collaboration with structured projects like The Drop, a wider reach of the Bristol Drugs Project, to approach these findings with candid conversations instead of heavy-handed punishments.

Bristol Uni’s drug policy announcing its “change in approach” making the link between providing useful advice and reducing harm. “We understand that a zero-tolerance stance is harmful and damaging as it prevents student reaching out”

— Tony Duffin (@tonyduffin) September 25, 2021

Via @BristolCable https://t.co/264ywNSpep

Even when the statistics are this stark, the family of Ishita Yadav from Newbury spoke of the undeniable allure of Bristol. Mr Yadav elaborated, ‘We’ve seen the rankings and Bristol is one of the top universities for her course’. Miss Yadav wishes to study Social Policy, and the family is of the opinion that Bristol is a vibrant city of opportunity and possibility where she can gain the necessary skills for her future career.

Opinion | Social inclusion is still a problem at the university

Bristol University one of ten worst for social inclusion in England and Wales

Before we went our separate ways, Mr Yadav wanted reassurance, despite the University’s academic reputation. He looked me in the eye and asked ‘Do you recommend Bristol?’, to which, considering all circumstances, I answered affirmatively.

In a statement made to Epigram, the Director of Home Recruitment and Conversion at the University of Bristol said: ‘We are resolutely committed to Bristol becoming a more diverse university. Due to a range of strategies, from outreach to admissions, and by working in partnership with our students, our 2021-22 intake of undergraduates in the UK was our most diverse ever. 75.5 per cent of new students joined us from state schools and 19.5 per cent from minority ethnic backgrounds. While proud of the progress made, we recognise even more needs to be done as we further diversify, and we look forward to working with current and future students to achieve our ambitious goals’.

Featured Image: Chris Bertram

Has your experience of Bristol University held true to its reputation?