By Lauren Sanderson, Second Year English and Philosophy

So, you’ve submitted your dissertation, your final-year tenancy lease is coming to an end, and your final trip to Jason Donervan is on the horizon. What now? With over fifteen years of education already under their belts, many graduates are asking themselves, ‘What’s one more?’. That’s right, it’s time to start your last-minute application for the infamous panic master’s.

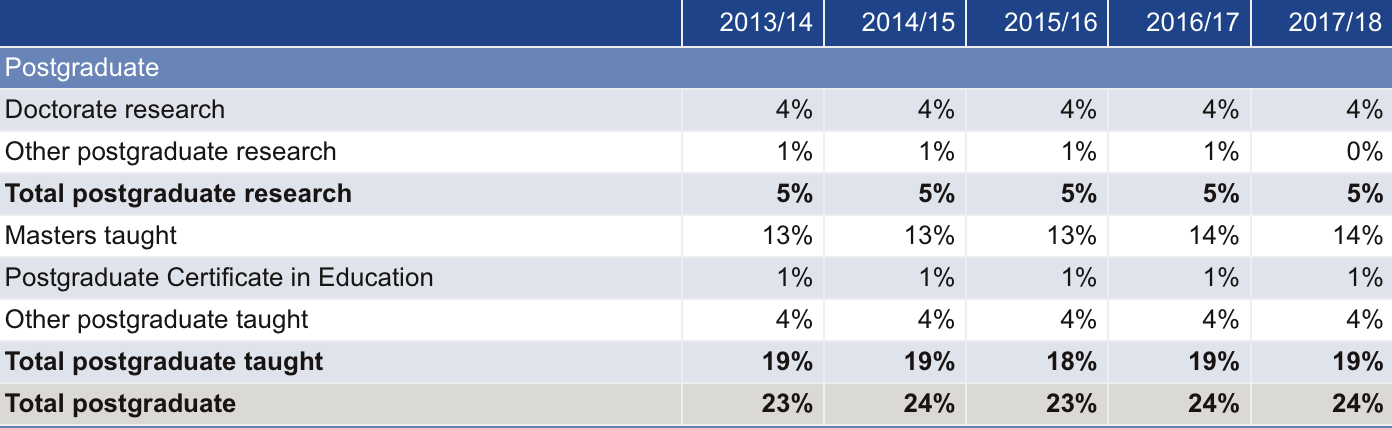

You’re not the only one. Since the 2015/16 academic year, the number of students going on to pursue taught postgraduate courses has been continuously increasing — 2020/21 saw a 16 per cent increase in enrolments for master’s taught courses compared to the previous academic year.

In 2019−20, 40.5 per cent of postgraduate students at UUK member institutions (Universities UK) were from outside the UK. These numbers have only been exacerbated since the government launched the Graduate immigration route for international students last year. This visa allows international students to remain in the UK and work for two years after they successfully complete a bachelor’s or postgraduate course.

Admissions expert Mary Curnock Cook said the rise is also in part due to ‘a collapse in confidence in the graduate employment market.’ Under-25s took the brunt of pandemic related unemployment, and in 2020 only 18 per cent of graduating students secured jobs, compared with an average of 60 per cent in a normal year.

The post-Covid graduate job market is a murky, overcrowded and shrinking pool that many final-year students feel unprepared for. The perception that employers expect graduates to have transferable, experiential skills before they even enter the workplace has left many students citing a lack of experience, practical skills, and vacancies as significant barriers.

I thought requiring years of experience for an entry level job was crazy but I just saw an internship that required previous internship experience... where does it end?

— Emileigh (@unestablishedme) April 25, 2022

English graduate Issy originally had plans to enter the publishing sector, but she told Epigram that she’s now waiting for decisions from postgraduate admissions teams: ‘The search for a graduate job honestly felt completely hopeless. There were so few roles in comparison to the number of applicants, and a lot of them were asking for the type of relevant experience that I’ve just never been able to find.’

Many so-called entry-level graduate jobs now seem to require up to three years of prior experience in a work environment. As the unlucky victims of the pandemic-stricken university experience who lost out on CV-boosting internships and in-person work experience, workforce newcomers may feel they’re already at a massive disadvantage.

how is this company gonna list a job as “entry level” and then list the first required qualification as “must have 7+ years of experience”??? Like if I had 7+ years of experience I would not be applying for this entry level position.

— maddie (@bettermaddie_) April 22, 2022

Issy further explained ‘I didn’t want to end up in a job that completely deviated from my career plans, and I didn’t want to put financial pressure on my parents by moving home unemployed. By March it seemed like doing a master’s in a subject I at least know I enjoy was my best option.’

If an undergraduate degree and motivation alone are no longer cutting it, final year students might need something more to guarantee their entry into the world of graduate employment. That might be relevant internships, or the connections to navigate a bewildering application process without being quickly eliminated by an algorithm. But not everyone has access to these advantages.

Whilst the comfortable route of further education might therefore look appealing, particularly in a time of economic turbulence, the question of whether postgraduate study is a worthwhile investment still remains: is a panic master’s going to open doors for you, or are you just postponing the inevitable?

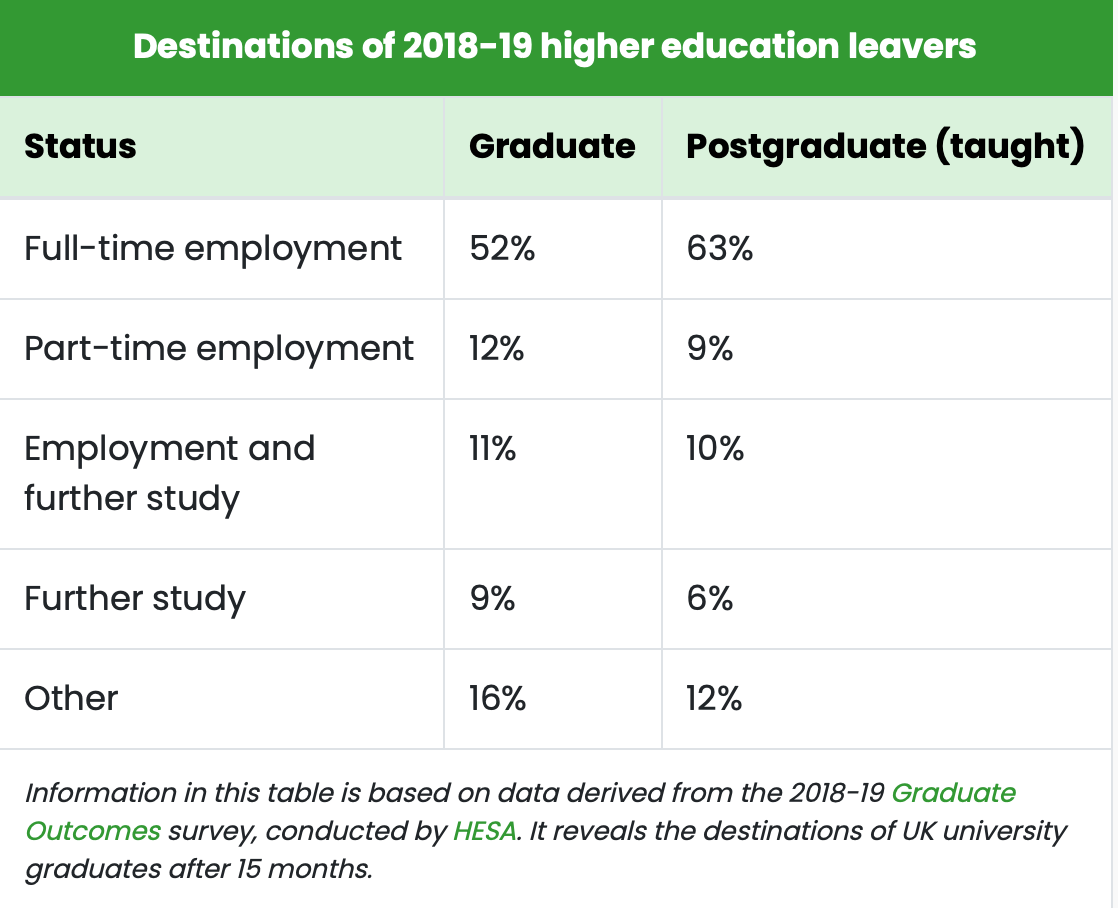

If future job security is your concern, the good news is that research indicates master’s study does have a career benefit — a Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) report from 2020 suggests that postgraduates earn on average 18 per cent more than first degree holders, six months after graduation. So, a relevant master’s degree could give you the competitive edge amongst a crowded cohort of candidates, demonstrating your ability to commit to a period of intense study.

In fact, the UK Commission for Employment and Skills predicted in 2015 that roughly one in seven jobs are likely to require a postgraduate degree by 2022.

One explanation for the growing desirability of postgraduate qualifications is that increased enrolment may have diluted the value of first degrees. In the past, candidates with undergraduate degrees were more expensive to hire because their qualifications were relatively rare — in 1990, only 19.3 per cent of the population participated in higher education. But that’s no longer the case. With almost half of the UK population now having a first degree, has the master’s become the new undergraduate?

And there could be further, more alarming knock-on effects. Postgraduate fees are market-driven rather than government set — that means when demand goes up, fees go up. The long-term impact of graduates seeking out further study to boost their employability could be that rising fees make the possibility of further study unfeasible for students from lower economic backgrounds. Since a high unemployment rate creates a law of supply and demand that works in the employer’s favour, this may have a detrimental effect for lower-income students applying for roles where postgraduate degrees are desirable. The socio-economic impact of a job market where postgraduate degrees accessible only to higher-income students give the upper hand in the eyes of the employer could be drastic.

The costs of higher education are already out of reach for many, and the financial commitment of a postgraduate course is certainly not to be overlooked. The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) reports that large increases in enrolment from 2016/17 coincided with the introduction of postgraduate loans for master’s students.

But with the average cost of a taught master’s degree standing at £8,740, and the government loan offering up to £11,836, a panic master’s may not be a tangible option for grads who can’t afford to cover their living costs. It’s not uncommon though for universities to guarantee fee reductions on postgraduate courses for their current undergraduate students — Bristol offers an ‘alumni discount’ of twenty-five per cent for recent graduates.

If you can afford it, taking on a master’s degree could be the short-term solution to your impending graduate disorientation. However, as more and more graduates turn to postgraduate study in the face of career uncertainty, the lasting impact on both the job market and the higher education sector remains to be seen.