By Meerabai Kings, Fourth Year, Biology

Hundreds of fossils dating back 230 million years unearth a lost world of innovation, showing that modern crocodiles represent just a snapshot of their prehistoric biodiversity.

When we think of crocodiles, we picture them in swamps and rivers, with their long snouts disguised as logs as they sneak up on prey. But they have not always lived like this, in fact they have not always had long log-like snouts. Recent research has unearthed that living crocodiles represent just a snapshot of 230 million years-worth of biodiversity.

Dr Tom Stubbs from the University’s School of Earth Sciences has found that Crocodylomorphs (the extinct relatives of crocodiles and alligators) came in ‘many weird and wonderful shapes.’ Furthermore, Dr Stubbs has shown that living crocs (alligators, crocodiles and gharials) have evolved slower than their showy ancestors and in doing so have remained conservative in biodiversity.

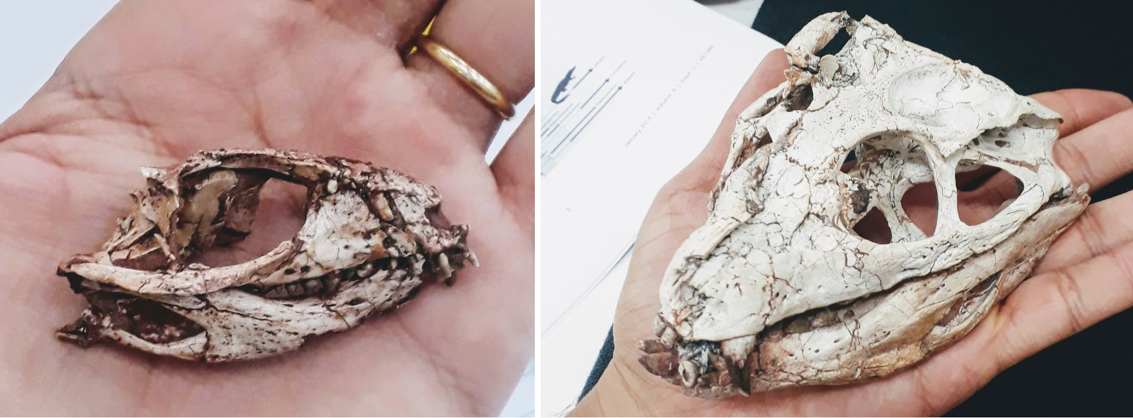

Their rich biodiversity allowed Crocodylomorphs to live in a number of habitats, some on land, some in the oceans and some in the stereotypical swamp. Thalattosuchians, the sea crocodile, was a marine species which swam in the prehistoric oceans snapping up fish. The land-dwelling notosuchians (two ‘pig-like’ skulls of which you can see below) adopted a range of diets, some species were meat eaters, others ate insects, some were even vegetarian! It is obvious that these extinct crocs were a lot more widespread than today’s swamp-living reptiles, but why?

Dr Stubbs and his colleagues have shown this occupation of different habitats was driven by rapid evolution in their skulls and jaws. Dr Stubbs analysed the skulls and jaws from crocs ranging from 237 million years old to present-day species. His research focussed on the shape and size of over 400 bones, as the shape of the skull and jaw relate to the diet and even habitat of an individual. Take notosuchians, for example. They have smaller skulls with shorter and broader snouts than living crocs (which you can see in the image above).

These broad skulls are robust and resilient against bending when biting down on prey. The slender skulls of living crocs (like that of the American Alligator, below), however, experience more stress on land but have greater efficiency in water – the perfect aquatic killing machine. Teeth all along the snout puncture any fast-moving prey multiple times, so it does not stand a chance.

Conservative crocs

This rich biodiversity is not reflected in the 26 living crocodylians; which includes crocodiles, alligators, caimans and gharials. All living crocodylians look remarkably similar thanks to their log-like snouts and slender skulls; making them all suited for semi-aquatic predatory lifestyles.

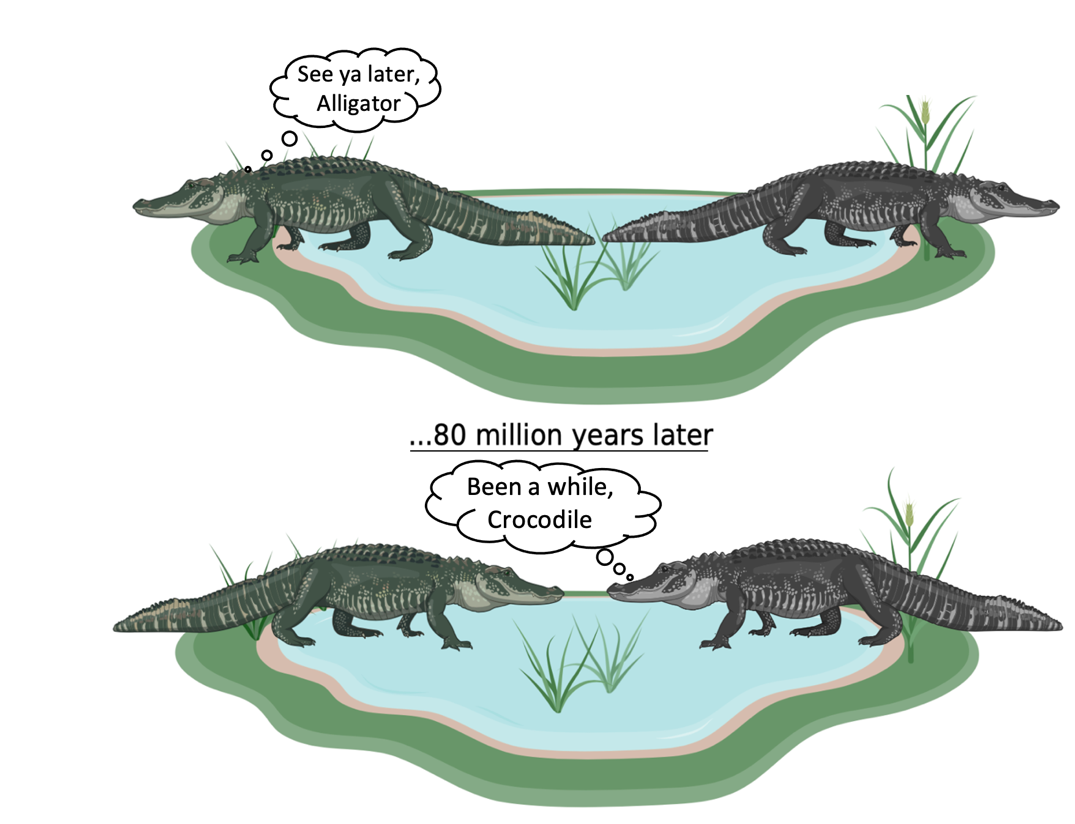

You could even be forgiven for mistaking a crocodile for an alligator, despite them having diverged into two separate species 80 million years ago. This is remarkable, especially when you consider that humans and chimpanzees went their separate ways only 6 million years ago and look vastly different.

This makes crocodylians one of the most conservative groups on the planet, as well as one of the least populated. ‘Today there are only 26 crocodylians, which is a very low number when compared to other equally ancient groups like mammals (6000) or birds (10,000)’, said Dr Stubbs. Prehistoric crocs seem to have a much more exciting array of morphology than our log-snouted friends, but where have they gone?

Where have all the crocs gone?

The explosion of crocodylomorph diversity took place ‘in the Cretaceous period, when climates were warmer’, offered Dr Stubbs, when asked what lead to the repetitive nature of today’s crocs. ‘The decline in morphological variety in the Cenozoic period is linked to reduced diversity of those strange land-dwelling notosuchians, with their unconventional diets and anatomies’, he went on to say.

Dr Stubbs pondered on the abnormal morphology and diet of extinct crocs being their downfall; ‘I think it a combination of competition with mammals, which now dominate the land and seas, and also climate, which has cooled significantly during the Cenozoic, potentially impacting the cold-blooded crocodiles’.

Modern crocs have evolved slowly over the last 80 million years, unlike their extinct relatives, who grabbed each ecological opportunity they could. Due to their slower, rather than snappy, evolution modern crocs have really become masters of the wetland habitat. It seems that slow and steady wins the evolutionary race after all.

Light drives the evolution of new butterfly species

Keeping a social distANTS

If you’re captivated by Dr Stubbs’ crocs you can read his paper here. Dr Stubbs aims to start solving the puzzle that is prehistoric biodiversity. He hopes, in his future research, to bring crocodiles, lizards, birds, mammals and amphibians into a large-scale analysis. ‘I want to understand how ecological opportunities, like expanding into new diets and habitats, underly biodiversity through time and the tree of life’ he revealed.

Work such as this will not only give us insight to extinct species but allow us to further understand how living species came to be – and perhaps where they are headed!

Featured Image: Unsplash / David Clode

Can you picture crocodiles looking like anything other than the ones we know and love today?