Georgia Marsh explores the trend that sees middle class young people adopting the cultural tastes of those lower in the social scale.

One of the most hotly debated social issues at the minute is the term ‘cultural appropriation’. It can be defined as individuals from one culture adopting components of another. Appropriation only embraces elements of a marginalised culture that are deemed desirable, such as dance or fashion, while ignoring elements that are less so, such as the realities of the oppression that many of these cultures face in the West. It’s problematic because the minority group in question are maltreated for exerting their culture, despite this theft by the majority who seek to popularise it.

Many people are conscious of cultural appropriation (whether they choose to acknowledge it is a different story) – but is ‘class appropriation’ its social counterpart? In the context of cultural appropriation, class appropriation takes elements of the lower classes and adopts them into upper class culture, disregarding the political and social implications of such theft.

However, is this just another term invented by so-called social ‘justice warriors’ as another means to condemn the middle class for something that’s, actually, not that deep? Or are there more sinister realities attached to this new kind of cultural theft?

The label ‘chav’ is almost outgrown now. While it is still exists as a means to poke fun at working classes, it’s been more-or-less dissolved to make way for ‘roadman’: the new-age chav. ‘Roadmen’ can be categorised as street youths who outsiders consider to be threatening due to their way of dress and manner of speech.

However this speech, as with the majority of street slang, is not perceived as a creative form of expression, but as a lazy and inferior form of communication. Being humans, we should be interested in evolving language and how slang is one of the vehicles upon which modern language operates.

In other words, wavey garms are fashionable if you’re white and upper middle class, but thuggish and chavvy if you’re anything else.However, this form of language is condemned and thought to be improper because of its working class origins – a damaging perception that stifles imagination and originality.

Take ‘wavey garms’ as an example. These are not, as my slang-inept friend believed, ‘clothes that blow in the wind’, but are instead (as a literal translation allows) ‘cool garments’. A favourite of Badock residents and ‘trustafarians’ alike – that’s rich kids who pay extortionate amounts of money to look like they have none – wavey garms are often, but not always, classified under the sports luxe umbrella.

Despite being one of the worst slang phrases ever invented, it also comes with problematic connotations. I attended a reasonably rough all-girls school in South London, so I understand first-hand the implications of dress. Our clothing affected the perspective that the public had on us. This, bar our uniform, mainly consisted of athletic gear – bags, trainers, hoodies, and tracksuits –associated with ‘rough kids’.

However this aesthetic, which the working classes were scrutinised for up to a few years ago, is now considered ‘edgy’ under sports luxe headings. In other words, wavey garms are fashionable if you’re white and upper middle class, but thuggish and chavvy if you’re anything else.

u whine bt appropriation, while wearing working class clothing without ever having worked hard in ur entire privileged live. #the triggering

— KRAMPUS (@salomon_hadren) March 10, 2016

This is a trend that has been cottoned-on to by the industry, too. Never mind labels like Yeezy or Alexander Wang who boast their wholly basic sport-inspired designs for enough cash to dry out your student loan, but previously accessible brands that could be found in JD Sports have introduced ranges such as Adidas Originals which charge upwards of £50 for… a plain black jacket.

Of course there’s a market for this, however the reason why sports clothing was originally so popular was because it was so cheap. Now that the upper classes have deemed it acceptable to wear outside of the gym or off of a sports pitch, it’s become gentrified through capitalist exploitation, and thus inaccessible to those who originated the trend.

Is there not something fundamentally wrong with that? Paradoxically, the style once made fun of for its working class roots is now being flaunted by upper middle class Tory voters through overpriced ‘vintage’ Adidas jackets. With this comes racial profiling and the demonization of lower classes.

This attitude is best exemplified with a quote from Skepta’s working class anthem ‘Shutdown’: ‘a bunch of young men all dressed in black, dancing extremely aggressively on stage, it made me feel so intimidated and it’s just not what I expect to see on prime time TV’.

It’s not that you shouldn’t wear what you want when you want – you should; it’s more that we should all be aware of the political and social implications that come with different kinds of dress.

Furthermore, it’s not that clothing choices should be attacked and critiqued, but rather that we should be conscious that upper middle class kids can wear whatever they want without being subject to negative stereotypes. While Jonathan from Buckinghamshire rakes in appraisal and Instagram likes from his private school pals as he poses with a zoot in his North Face gear, inner city youth are denied opportunity and freedom due to dressing in the exact same manner.

Class – like culture and ethnicity – is not a costume; it’s not something you can always turn on and off. Jonathan loves the creativity, status and comedy of the roadman aesthetic, but what is he doing for the working classes by appropriating their individuality and voting for the Conservatives because it benefits him?

This is a sentiment that Beth Smith, a First Year English student from London, agrees with: “The problem is the double standard – its middle class young people who contribute to – and reap the benefits of – a system which actively prevents social mobility, and not seeing the irony; they are taking the style, music, slang, from a group of people who they simultaneously help to prevent from having the same opportunities as themselves.”

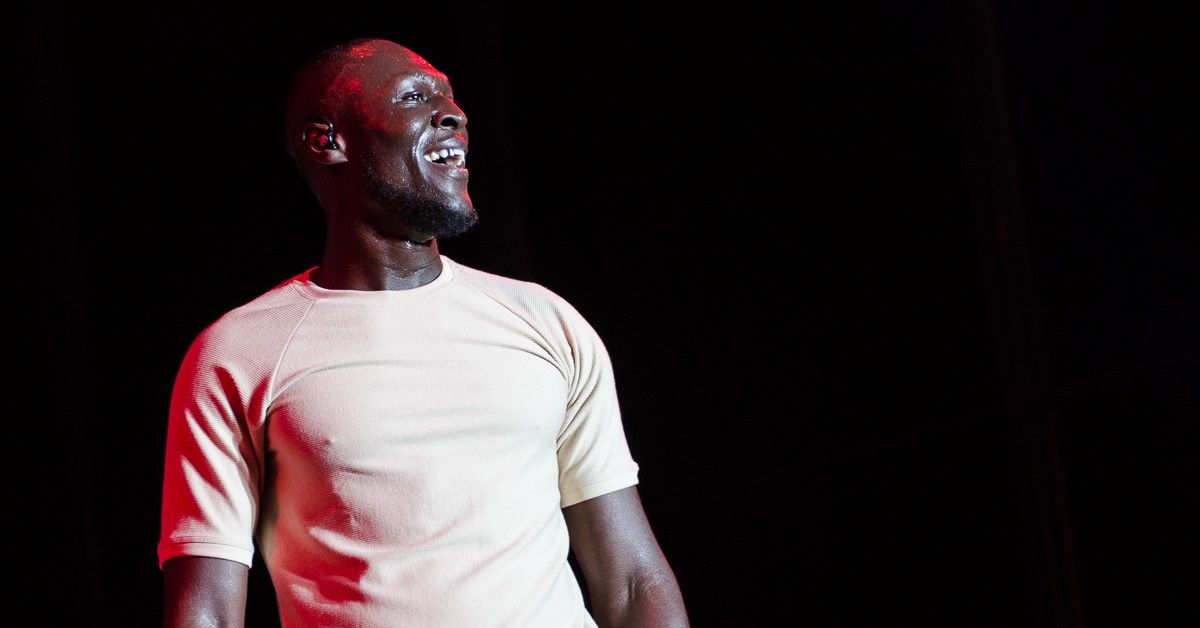

The difficulties of class appropriation that Beth Smith has touched upon is pervasive in more unlikely places. The UK grime revival, for example, is a highly politicised emergence of popular music. The past few years has seen grime move away from its rich history as an urban underground effort, and sail towards the forefront of mainstream music.

Though it’s about time that a spotlight is shining on such a dynamic, vibrant and quintessentially British genre, the message of grime is often being glossed over by this new-wave of fans. It’s not about the garage beats or the quick-witted lyricism, but about recognising the message that’s staring the listener in the face. For example, it’s an impossibility to appreciate Kendrick Lamar and not be aware of and involved in the social commentary of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US.

The same sort of problems are prevalent in UK society, and grime is all about this. Grime is about finding a powerful, distinctive voice in the midst of the everyday struggle: it tackles classism problems, with particular emphasis on attitudes towards black youth, which our modern sensibilities should acknowledge as significant social issues. Therefore, Etonians bigging up Stormzy, while a nice gesture, is kind of missing the point.

Perhaps class appropriation is an over-cooked issue. Maybe its subject matter is tired, and vocalised only by kill-joys and over reactive bloggers; no wonder that the mention of it is met with eye-rolls and disinterest. Yet, at the same time, the social and political implications of class appropriation are often too large to ignore and only toughen the rigidness of our class system.

Appreciate and celebrate by all means – if this is your scene, indulge in it. However, don’t do so without actively being part of solutions. By being ignorant of this, you must be aware that you are part of the problem.

Featured image: flickr / bSides

Do you think 'working class appropriation' is the new cool? Does it have a longer history? Let us know in the comments below or tweet us @EpigramFeatures.