Ruth Day shares her experience with Borderline Personality Disorder - a serious mental illness often grossly misunderstood - and explains why we must start openly discussing the presence of personality disorders

From an early age, I can remember always feeling things intensely, and struggling to manage my emotions.

In secondary school I began to spiral down, starting to have suicidal thoughts, hear voices, and struggle with feeling empty all the time. I self-harmed or was impulsive to try and fill this hole. I always had an unstable relationship on the go, platonic or romantic, where I would let myself be completely swallowed up by the other person, and then break down when I perceived they were going to abandon me.

BPD is a personality disorder that centres on the inability to manage emotions effectively.I did not know what was going on, and even when I was diagnosed with depression and anxiety, that couldn’t explain the intense emotions which I was struggling with every day. It was only until I was offered DBT when a psychiatrist suggested that I had Borderline Personality Disorder. Everything seemed to make sense and fit into that diagnosis, from my intense emotions, to my unstable relationships. But knowing the diagnosis doesn’t solve all of your problems. In fact, with BPD, it can cause more problems.

There is a reason why doctors tell you not to look up your illness on the internet when you’ve just been diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. If you do search, you will find posts discussing how manipulative and attention-seeking people with BPD are, forums entitled ‘how to recover from dating a borderline’ and numerous self-help books on ‘how to love someone with BPD’, all of which make you feel small and worthless on top of having a debilitating mental illness.

Not much is known about personality disorders, they are highly stigmatised and rarely spoken about. But personality disorders are genuine, serious mental illnesses, and there is a desperate need for conversation to be opened up about them so that more people are unafraid to come forward and get help if they think they are living with this illness, instead of refusing treatment and diagnosis because of the stigma that they will invariably face. This is why I am here to dispel the myths about BPD and hopefully inform you of what this disorder is like.

The way borderline personality disorder (BPD) is talked about in and outside of the mental health community needs to change. We have to start talking about mental disorders beyond anxiety, depression, & dyslexia.

— andy (@ungovernabIe) November 27, 2017

BPD is a personality disorder that centres on the inability to manage emotions effectively. It is also characterised by unstable interpersonal relationships and an unstable sense of self, and can lead to impulsivity, suicidal gestures, and transient symptoms such as disassociation or paranoid ideas. Roughly 1.6% of people have this disorder, and BPD frequently coexists with other illnesses such as depression, anxiety and eating disorders.

BPD is diagnosed by identifying nine main symptoms, and to be diagnosed you have to meet at least five of these. The first is an extreme fear of abandonment - sometimes I sabotage my relationships because I’m so scared of the other person leaving, and perceived abandonment can send me spiralling into depression. Another symptom is a pattern of intense and unstable relationships, which often swings from idealisation to devaluation, and relationships seem either perfect or horrible with no in-between.

Despite this structured diagnosis system, BPD is often highly misdiagnosed, and people with BPD often don’t get the help they need

People with BPD also tend to have intense emotions, which can oscillate up and down in a matter of minutes. Sometimes these feelings can be so intense that they physically hurt, and it is very hard to manage this rollercoaster of emotions. One of these intense emotions is explosive anger which seems impossible to control.

Another symptom is an unstable sense of self, where your goals, likes, sexuality and more are constantly changing, and you can feel like you don’t know what you want from your life, or who you are as a person. If you have BPD you tend to be self-destructively impulsive, taking risks with things such as sex, drugs, alcohol, binge-spending, and shoplifting, and also harm yourself impulsively.

This impulsivity can come from needing to deal with chronic feelings of emptiness. I find that this feels like there is a raw, dark cave in my chest, which I need to keep filling to avoid this intense feeling. The last symptom is what professionals call ‘transient or paranoid ideations’. This can be feeling that someone is out to get you, hearing voices, or dissociating for long periods of time, where you can feel like you’re not part of your body or simply not remember months or weeks of your life.

These symptoms manifest themselves differently in each person, and to a varying degree, so no one person experiences BPD the same as another. Despite this structured diagnosis system, BPD is often highly misdiagnosed, and people with BPD often don’t get the help they need.

Saying I struggle with borderline personality disorder is such an easy way to explain why I struggle so much with relationships and why my thinking is so black & white, or why I dissociate so much, or why I struggle with impulse control

This is why we need to get rid of the stigma surrounding personality disorders and make it easier for people with BPD to access therapy. We must talk about mental health, be it what we’ve personally experienced, or just dispelling general myths about mental illnesses to challenge the ignorance and prejudice people with mental health conditions face.

If you recognise that you are experiencing some of these symptoms, or struggling with your mental health in another way, seek support if you can, because in a flash everything can become unbearable and you can fall into crisis.

I wish I had reached out for help earlier, and hadn’t given in to the stigma by remaining silent about experiencing difficult emotions and suicidal thoughts. I may have waited too long before seeking treatment, but it’s never late to learn how to manage your symptoms and start on the road to recovery.

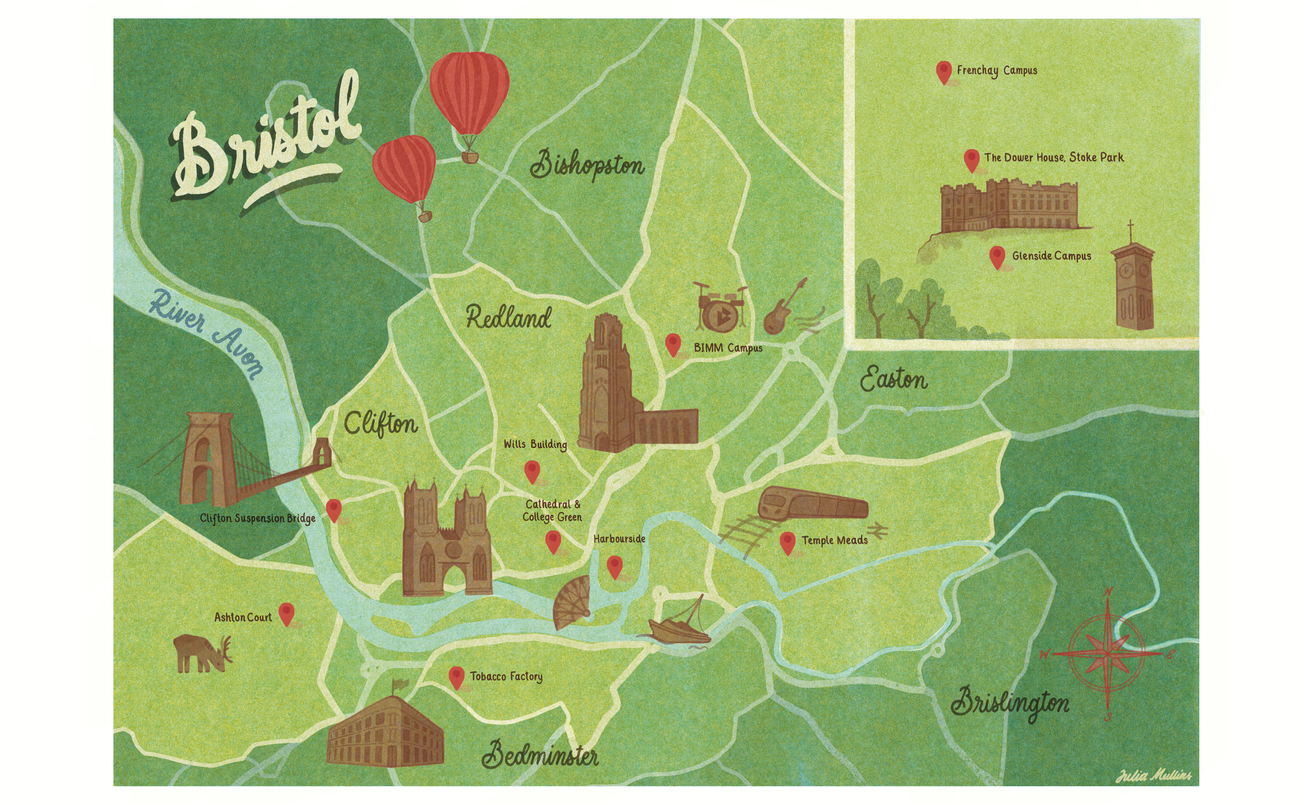

Featured Image: Flickr/ Val489

If you relate to any of the information in this article, don't hesitate to get in touch with Epigram Wellbeing for more information on who you should contact or call the student counselling service on 0117 954 6655.

Facebook // Epigram Wellbeing // Twitter