By Sofia Athena Roberts, Third Year, Classics

I purchase an iced matcha latte two or three times a week. It’s popular, it looks enticing, and I quite like the taste. However, I was unaware of the rich history of the product I was consuming.

This summer, I had the privilege of visiting Japan. In the tranquil streets of Kyoto, I stepped into a traditional wooden tea house (chashitsu). Shoes off, kimono fitted on, the experience was deeply respectful and enlightening. We learned that during the Edo period (1603–1868), tea house entrances (nijiriguchi) were intentionally low - approximately 60 cm x 65 cm. The small size forced all guests, including high-ranking samurai, to crouch and crawl inside, symbolically removing their swords and their social status at the door. It marked a transition from the outside world into a space of quiet reflection and sacred unity. The bowing gesture this required was not only functional but deeply rooted in humility.

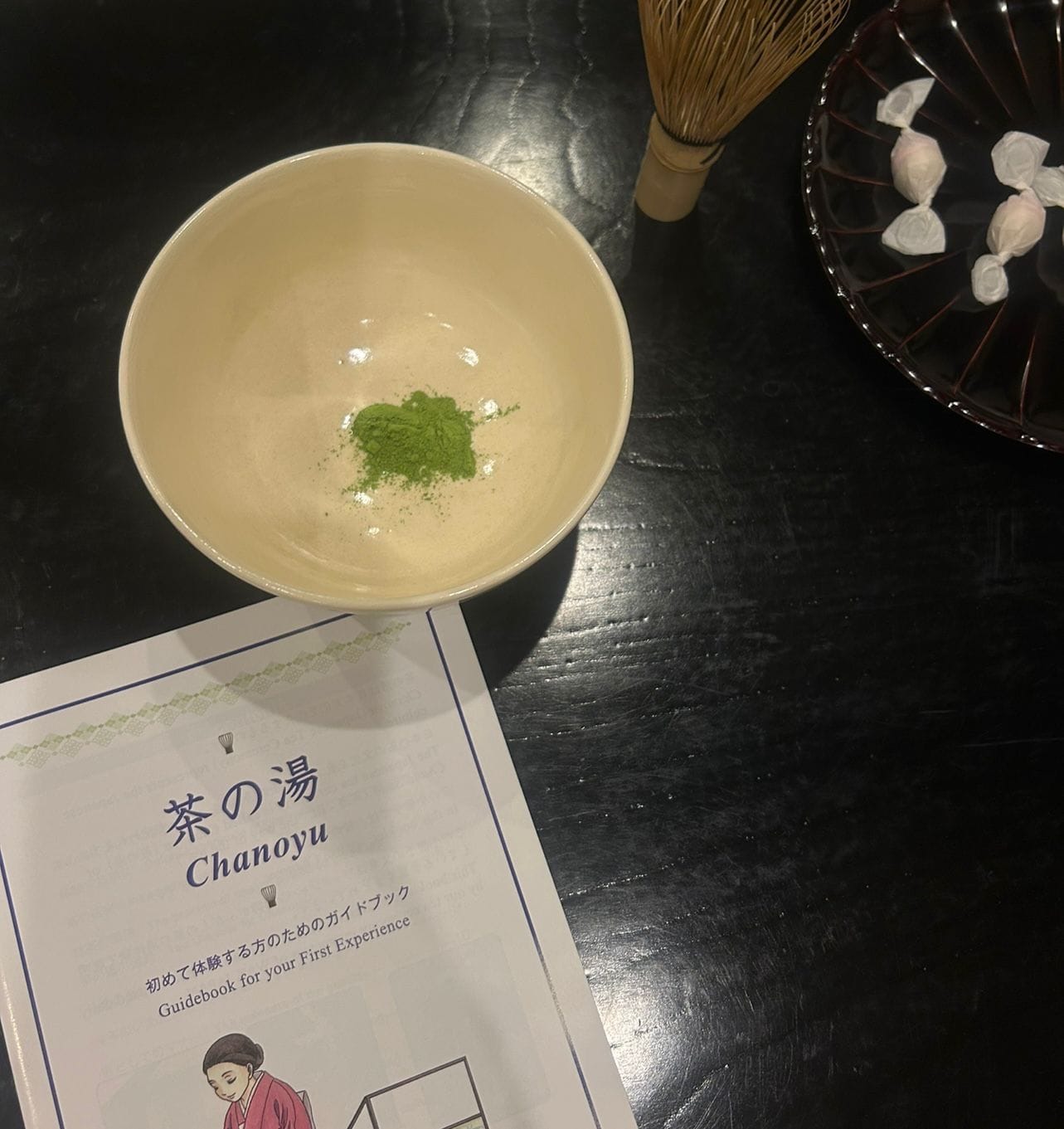

Inside, we were introduced to the simple yet profound tools of the tea ceremony: a kettle, a bamboo whisk (chasen), and a bowl of fine, bright green powder called matcha. Before sipping, we were taught to rotate the chawan (tea bowl) so that the front-facing design was turned away, another subtle act of humility and deference. We were requested to say to the person sitting on our left, ‘osakini itadakimasu,’ which loosely translates to ‘I humbly receive before you.’ It’s a gesture of awareness, mindfulness, and respect - the values that form the heart of chanoyu, the Japanese way of tea. The ceremony is intended as a meditative practice rooted in Zen Buddhism, focusing on harmony (wa), respect (kei), purity (sei), and tranquillity (jaku). These principles are not just abstract ideas but are present in every movement of the host: from cleaning the utensils to folding the cloth, to whisking the tea.

I was familiar with matcha, but this version was different. It was unsweetened, no blueberry or pistachio syrup, not poured over ice, or mixed with oat milk, and it wasn't being handed to me in a busy queue. Anytime I walked into a ‘hip’ coffee shop or even a chain brand like Starbucks, I would find a matcha latté on the menu.

But what exactly is matcha? And how did we go from something so sacred and cultural, to something so widespread and material?

'while many of us sip our iced oat matchas between classes or deadlines, it is still easy to forget that matcha originates from something far more sacred.'

Matcha is a finely ground powder made from shade-grown green tea leaves, specifically a variety called tencha. Unlike typical green tea, where leaves are steeped and the water is consumed, matcha is whisked into water, and the whole leaf is ingested. Why has it become so popular, especially among students?

TikTok's #matchatok has amassed millions of views, and is especially popular among Gen Z , who praise it for its ‘calm energy,’ aesthetic appeal, and association with wellness. The health benefits are what attracts most people and have been marketed well by influencers. Matcha is rich in antioxidants, particularly catechins, and is also known for its combination of L-theanine (a calming amino acid) and caffeine, which together create a more balanced, focused energy compared to coffee. This has made it especially appealing to students seeking a calm, sustained concentration boost during, and outside of, term time. Long queues stretch out the door Black Sheep Coffee on Queens Avenue every Monday, thanks to their £2 drink deal, a godsend for students (and something I’d totally recommend, if you have the time to wait). But while many of us sip our iced oat matchas between classes or deadlines, it is still easy to forget that matcha originates from something far more sacred.

However, not everyone is a fan. My dad, for example, says it tastes like grass - and in all fairness, he’s not entirely wrong. Matcha has a vegetal, slightly bitter flavour profile, often described as umami.

Nevertheless, it has been reported that due to the high demand of the product, Japan's matcha supply is dwindling. Prominent matcha companies like Ippodo and Marukyu Koyamaen have imposed sales restrictions or halted certain products due to limited supply. According to sources like The Japan Times and NHK, ceremonial-grade matcha has become increasingly difficult to obtain domestically, as much of it is now exported to meet international demand. This shift risks eroding the centuries-old traditions.

Moreover, much of the commercially available matcha abroad is culinary grade, intentionally more bitter and often masked with sugar or syrups, rarely resembling the unsweetened, whisked matcha served in a quiet Kyoto tea house. In some cases, the matcha isn’t sourced from Japan, with suppliers from China or Korea meeting international demand but offering different flavour profiles and lacking the same cultural ties.

The journey of matcha, from the ritual to the trend, is compelling, yet complex. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying matcha in a modern setting, as I do too, but mindfulness extends beyond consumption. Next time you order a matcha latte, consider pausing a moment to appreciate its legacy - the centuries-old Japanese rituals, the artistry, and the fragile ecology behind each cup.

Featured Image: Epigram / Anna Dodd

Where is your favourite spot in Bristol for matcha?