By Alana Evans, Second Year, Biomedical Science

Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, the use of antibacterial products has skyrocketed into misuse, leading to the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis currently facing the scientific world. Once upon a time, these agents were viewed as a silver bullet - a miracle cure to rid the world of its heavy disease burden. Coupled with the rise of antibacterial products came a societal fear of the dreaded ‘germ’. As a child, I remember staring at the soap bottle in the bathroom which bore the tag ‘kills 99 per cent of bacteria!’ and worrying about what that one per cent would do to me. Our health anxiety has been exploited by hygiene product manufacturers, manifesting in a proliferation in the number of antibacterial products available for purchase.

It is worth noting that the antibacterial substances which make up the cleaning products seen in most households today share similar targets with the antibiotics a doctor would prescribe for an infection, but they are not the same. The primary difference is that antibiotics work to treat active disease, whereas antibacterial products are employed to prevent transmission of disease-causing pathogens.

Theoretically, a healthy household shouldn’t require many antibacterial products at all – in everyday settings, plain soap and water suffice for removing dirt, oils and microbes. Soap and other detergents function by surrounding pathogens and grime, and get flushed away as we rinse. Some cleaning products incorporate extra chemicals such as the antibiotic triclosan, which actively kill bacteria – this is what makes them antibacterial. Interestingly, studies show that these products have no obvious additional benefit for the majority of people. Many countries have forced companies to phase triclosan out of their products, citing concerns over AMR and toxicity. If you were ever told not to swallow your toothpaste as a child – this is one of the reasons why!

The public are hardly to blame for the obsession with being germ-free. We are constantly bombarded with marketing for products which will rid us and our loved ones of all the nasty microorganisms which are supposedly out to do us harm. It is now even possible to buy bed linen and mattresses laced with antibacterial agents. So, what’s the issue? Surely if we banish the bacteria, we also say goodbye to our fears of disease? Sadly, it’s not that simple, and as we know, there is no such thing as a miracle cure.

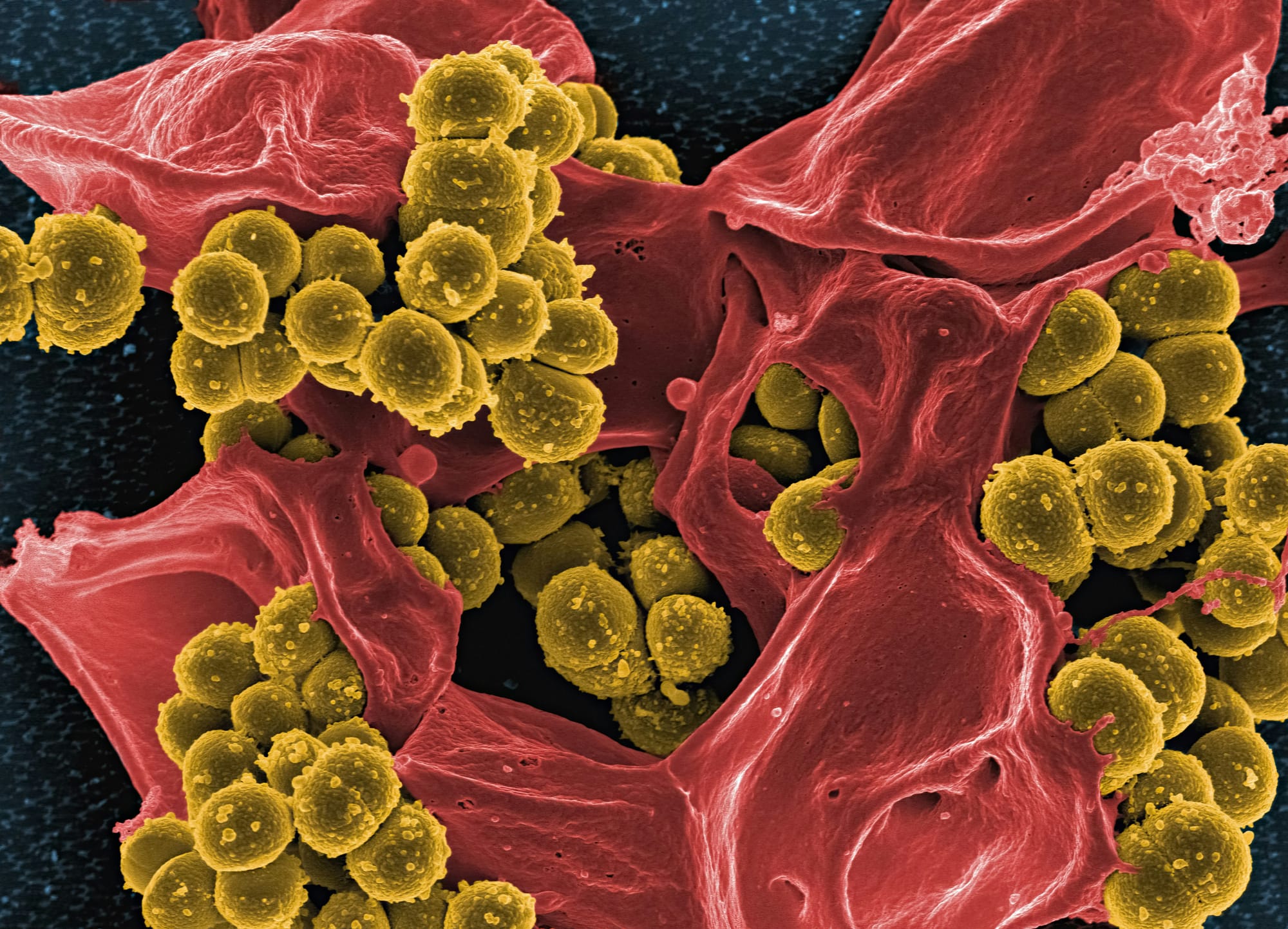

The main issue is that bacteria have existed for far longer than we have and are not willing to go down without a fight. In essence, the worry is that by excessively using antibacterial products, we are knocking out the population of ‘weak’, easily killed microbes and leaving behind the ones which are resistant to our chemicals. Links between use of antibacterial products and community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) – which causes a range of skin and soft tissue infections – have been found by investigators. The problem with resistant bacteria is that they are harder to treat with antibiotics, which brings the risk of stubborn and persistent infection.

There is also evidence which suggests that excessive hygiene measures during childhood can increase the incidence of allergies. The idea behind this is that the immune system needs sufficient stimulation from the microflora that naturally exist on or around us. Remove these microorganisms while a child is still developing, and the immune system is too sheltered to mature correctly. One study in Switzerland found children raised on farms, where certain allergens are more prevalent, were significantly less likely to develop hay fever compared to their urban counterparts.

It is equally important to remember that many bacteria do us good. The trillions of commensal and mutualistic bacteria we host offer a large amount of assistance with digestion, nutrient production, immune regulation and even help fight pathogenic bacteria. We have lived in a bacteria-filled world since the beginning of man, and believing we can rid ourselves of them is dangerous.

In short, whilst it is vital to control pathogenic bacteria to prevent disease, it is just as important to do this without destroying the microbes which do us no harm. Many scientists believe that the most prudent way to do this is through a much more considered and careful usage of antibiotics and antibacterial products than we are currently employing.

Featured Image: Epigram / Alana Evans