By Eleanor Bate, Film and TV Deputy Editor

As someone who devoured Barbarian for all its unpredictability and disturbing turns, I was understandably excited for the release of Zach Cregger’s sophomore feature, Weapons (2025). He carries the momentum of his debut with ease, and after just two films it’s clear who he is as a director. Cregger trusts audiences to sit with discomfort, confronting social taboos, anxieties, and recurring motifs of the home as an unsafe space. His horror isn’t about escapism, as so much mainstream cinema is today, but about direct confrontation. And honestly, I can’t wait to see where he takes us next.

Cregger himself refuses to impose a single meaning on Weapons, preferring audiences to develop their own interpretations. The story was written to unfold organically, guided only by a basic idea rather than a strict direction. Writing is a cathartic process, and personal or social contexts inevitably emerge in the narrative, whether consciously or subconsciously. As a result, the film doesn’t hand viewers a definitive metaphor—but rightly so, as everyone is free to form their own understanding of what it’s truly about. In this piece, I will explore several interwoven readings of Weapons, each of which has sparked significant discussion since the film’s release.

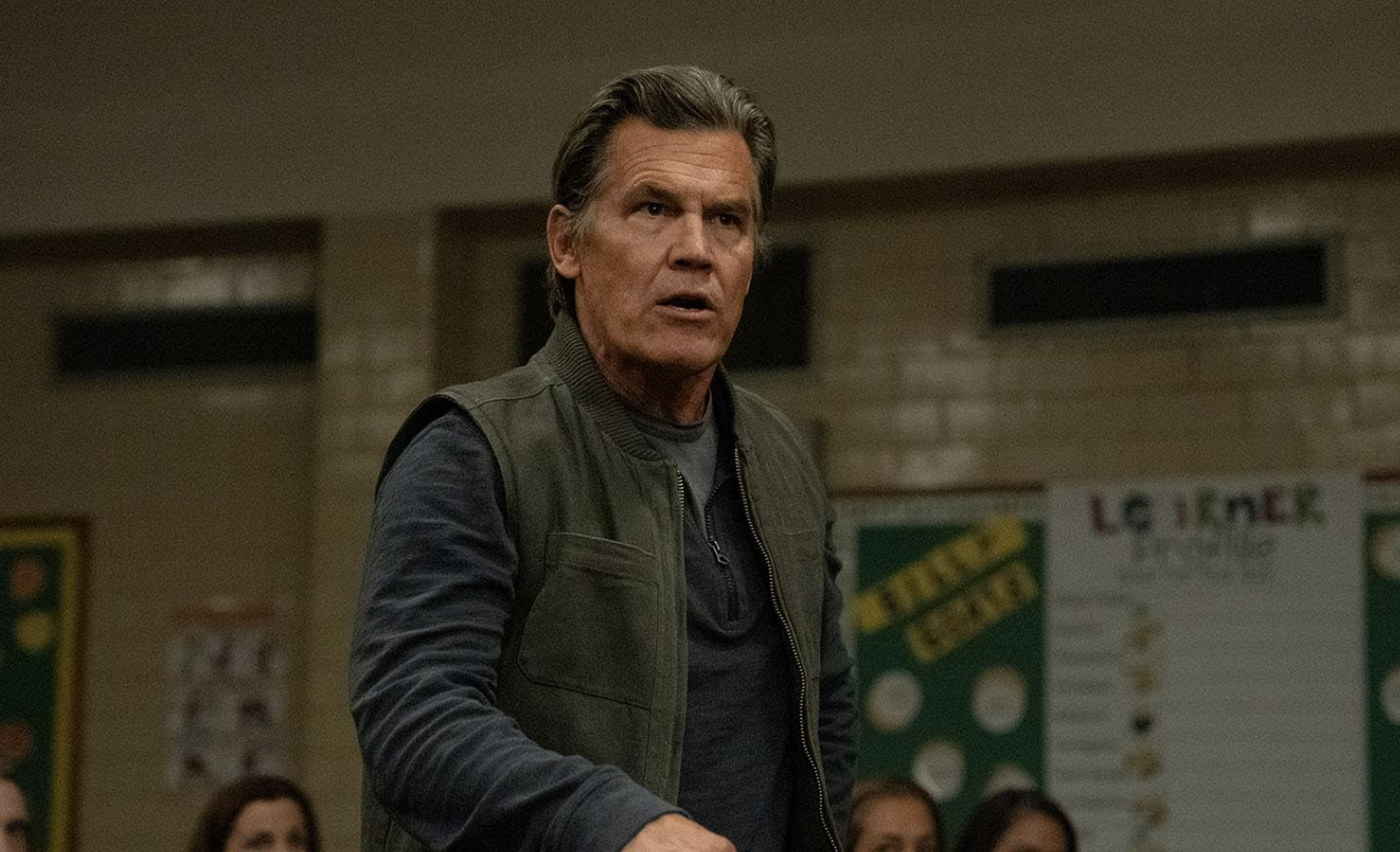

At its core, Weapons is a story set in the small suburban town of Maybrook, where, one night, 17 out of 18 children from the same class mysteriously vanish simultaneously at 2:17 a.m., leaving their homes only to disappear into the night, never to return. The film follows the lives of several characters in an episodic, Pulp Fiction-like structure: the children’s teacher (Julia Garner), a grieving parent (Josh Brolin), a police officer (Alden Ehrenreich), a homeless drug addict (Austin Abrams), the school principal (Benedict Wong), and the sole remaining child (Cary Christopher). The narrative is non-linear and emotionally driven, weaving together their experiences to create a haunting and fractured portrait of the town.

Now for the juicy stuff. It’s not hard to see why some viewers read Weapons as an allegory for school shootings. The film is set in a small, ostensibly safe American town, where all but one child in a class vanish; there’s the AR-15 visual imagery, and, well—the title of the movie is literally Weapons. Many audiences went in expecting this connection and drew parallels to gun violence and mass shootings as they watched. That said, Zach Cregger has explicitly stated that the film was not intended as a school-shooting metaphor, though he does embrace multiple interpretations.

"I always like a title that’s opaque. I think it invites you to consider the movie one layer deeper, and to try and make sense of it. I’ve heard a couple of people articulate why [it’s called that], and I think they’re all right. " - Zach Cregger for Vanity Fair.

Critics have drawn parallels between Weapons and real-life school shootings, particularly the Sandy Hook Elementary School tragedy. The imagery—a floating AR-15 (the weapon most commonly used in mass shootings), a grieving elementary school adorned with floral memorials, and the mass loss of children—feels all too familiar in modern America. Some theorists have suggested that the 2:17 time references the number of members of the U.S. House who voted on gun reform, though this seems more likely a strange coincidence. That said, even if unintentionally, it’s hard to imagine that the reality of such events didn’t seep into Cregger’s writing process on some level.

Beyond what might initially read as on-the-nose school shooting imagery, this reading gains depth when considering systemic failure. The school is meant to be a safe haven, yet the leadership and authority figures fail to protect the children. There were clear warning signs from Alex, the 18th child in the class, that went unnoticed: his sudden changes in behaviour, no longer being picked up by his parents and having to walk home alone, the strange appearance of an unfamiliar aunt, his withdrawn quietness, and his mysteriously covered windows—all signalled that something was deeply wrong. Had the appropriate authorities paid closer attention, they might have discovered sooner that Alex’s parents were under a witch’s control, with Alex forced to sustain their physical bodies, before she could influence the other children. This failure to recognise and act on early warning signs resonates strongly with the school-shooting metaphor, highlighting how those tasked with protection, from politicians to school administrators to law enforcement, fail far too often.

While this may seem like a plausible interpretation, Cregger’s discussion of his personal experiences as inspiration for the film, and particularly for the character of Gladys, offers a whole new layer of understanding.

Cregger described Aunt Gladys, incredibly portrayed by Amy Madigan, as an allegory for the insidious nature of addiction, creeping into the home and warping family relationships. While this may not be the interpretation audiences initially expected, the deeper you look, the more meaningful and haunting it becomes.

Several motifs reinforce the allegory of addiction. The triangle-circle motif, reminiscent of an AA logo, appears in the credits and bell visuals. The character arcs of Justine, the teacher, who struggles with alcoholism and falls deeper as pressures mount, and Paul, the cop, who is urged by his wife to attend AA but instead relapses at a bar, leading to infidelity, are more obvious reflections of this theme. Yet the most unsettling representation is Gladys herself, as addiction incarnate.

Cregger has revealed that Aunt Gladys and her witchcraft are autobiographical of his own experiences with parents plagued by addiction.

“The house becomes a scary place. You can go to school and act like everything’s cool, and then you come home and you hide from a zombie parent. That felt so real to me.”- Zach Cregger for Vanity Fair

It is an incredibly interesting, albeit slightly unorthodox, metaphor for addiction, but it works brilliantly, evoking an ominous sense of dread for viewers. Aunt Gladys enters the home one day, immediately disrupting the idyllic family dynamic that once existed and forcing Alex’s parents into vegetative states. She threatens Alex, warning that if he tells anyone about her existence, she will harm his parents, make them hurt each other, or even hurt him—a pattern of threatening and violent behaviour often seen in addicts.

As Cregger explains, Alex is forced to become a parent. His own parents are no longer present in any meaningful way beyond their physical bodies. He begins grocery shopping and feeding both them and himself, because if he doesn’t, who will? Certainly not his parents, who are under the spell of addiction. Gladys manipulates, threatens, compels, and transforms, and her ability to activate those around her mirrors the triggers and control addiction can have over behaviour. Addiction hijacks lives, disturbs home life, and fractures family dynamics.

Alex is completely isolated, returning each day to his 'addict parents,' forced into the role of caregiver and constantly threatened by violence and fear. He longs for the return of his once loving parents and yearns for Gladys, the embodiment of addiction, to be cast out forever. By the movie’s close, it is revealed that Alex’s parents never recovered and now live in a care home. Having been under addiction’s spell for too long, they are permanently scarred; life cannot return to how it once was. It is a beautifully poignant yet heart-wrenching context that transforms the story on a rewatch, imbuing every scene and motif with deeper, stronger meaning.

So, which is the true meaning of Weapons—the school shooting metaphor, systemic failure, the allegory of addiction, or the invasion of foreign entities? The answer is: all of them. The film works best as an overlapping interpretation of multiple metaphors, each converging on the idea of 'weaponising' ordinary people.

Those under the witch’s control are literally weaponised, acting at Gladys’ will. Yet the movie is full of other examples of unsafe and weaponised environments: a young homeless man struggling with drug addiction, an aunt exploiting a child, the corrosive effects of alcoholism seen through the teacher and cop, failures of leadership and authority, toxic masculinity, police corruption. These are not incidental details—Cregger is showing us the very real dangers that people, especially children, face in their daily lives, drawing inspiration from his own childhood experiences.

All of these represent different kinds of weapons, destroying the innocence of kids today in America: alcoholism, drugs, abuse, corruption. While Cregger may not have intended an overtly political message, the film delivers a poignantly social one about the protection, or lack thereof, of children.

All in all, Weapons is at its strongest as a piece of art when it doesn’t tell us how to think or feel, but instead evokes emotional and interpretative responses from its audience. It embraces ambiguity. While I’ve touched on just a few readings, there are countless others, all shaped by our personal contexts as we watch. That is what makes it a successful work of art. We are human, we constantly search for clear-cut answers to make sense of our traumas and our reality. But Cregger defies the unrealistic expectation of a neatly tied-up story. He wants us to be uncomfortable, to feel deeply, and he does an exceptional job of achieving just that.

4.5 stars.

Featured Image: IMDb/ Quantrell Cobert

How did you feel about Weapons, did it achieve its job as an uncomfortable horror?