By Sophia Lee-Baum, Third year, Neuroscience

October of first year. Tucked in for an early night, after a relentless cycle of evenings haunting the Berkeley and stumbling home from the triangle, followed by bleary-eyed Badock breakfasts, and rushing for the U1 on minimal sleep. A series of weeks thoroughly enjoyed, but at the detriment of a healthy sleep schedule. Occasional naps after lectures had just about got me through, but only just. It didn’t take long before blissful sleep washed over me.

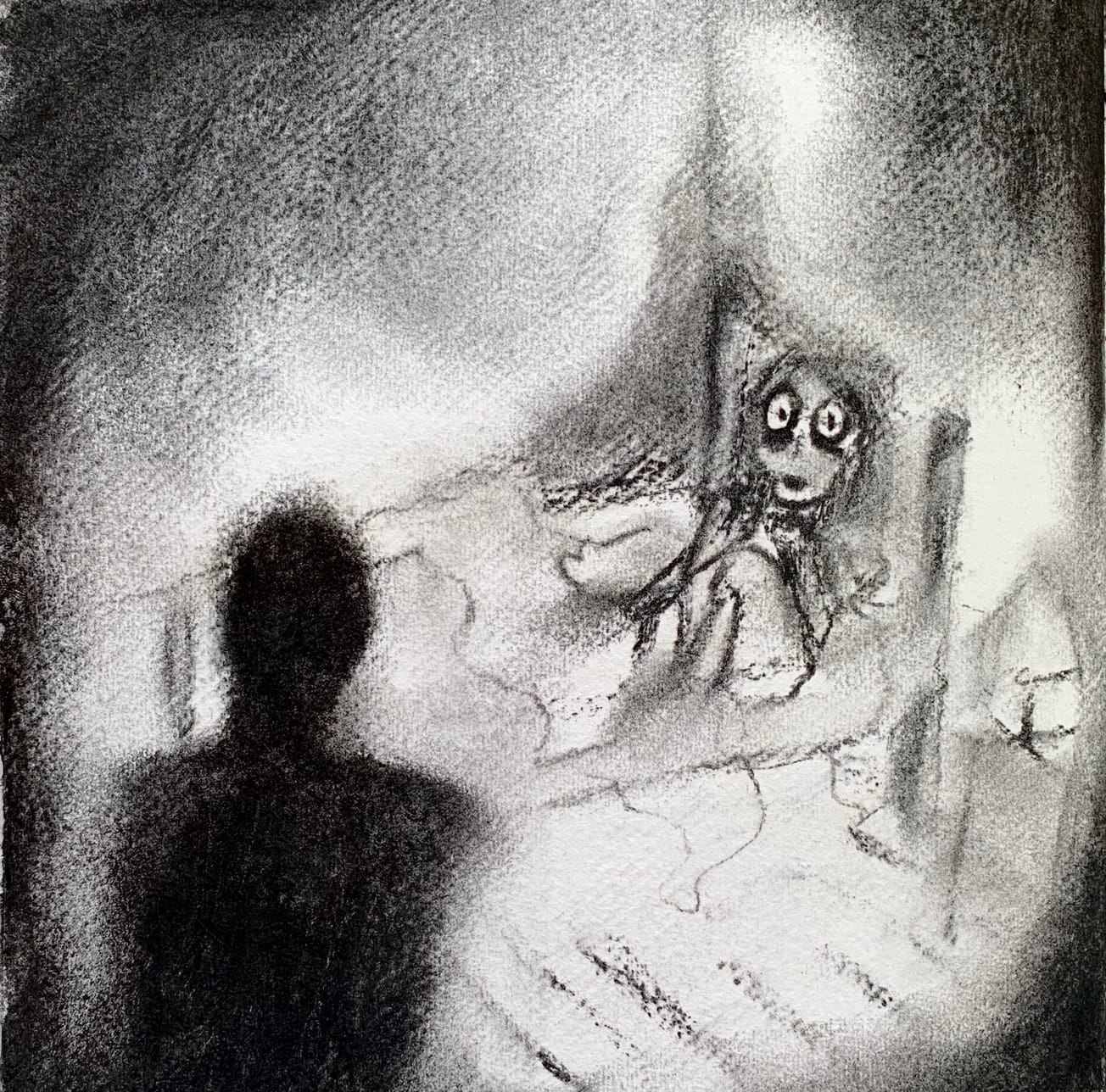

It felt like only moments later, an unsettling weight on my chest brought me begrudgingly back to consciousness. A tall shady figure, watching me, from across the room. Panic immediately set in. Reflexively, I tried to jump up against the wall: my body was unresponsive. My eyes flicked across the room, exercising the only control I had, to try and make sense of what could possibly be going on.

Realisation set in quickly – I was awake in a nightmare. The next agonisingly slow minutes were spent trying to ‘wake up’ and willing the figure in the corner to disappear. Despite my understanding of the situation, the unshakable panic it had instilled followed me through the next couple of days.

This freakish phenomena of visits from strange paranormal visions and figures featured twice over the following two years at Bristol and always coincided with my highest stress and lowest sleep health. These spooky sightings were what’s known as sleep paralysis: hallucinations in a state of clear environmental perception, often when you first fall asleep or start to wake up. Around 28% of students are likely to also have experienced sleep paralysis at some point. It begs the question - how many other first year bedrooms are haunted by real life ghosts?

The factors increasing risk of sleep paralysis are characteristic of the stereotypical student lifestyle. Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological condition impairing the brain’s ability to control its sleep and wake states, often featuring sleep paralysis as a symptom. Isolated sleep paralysis (ISP) is independently occurring rapid eye movement (REM) parasomnia, featuring incubus hallucinations (the sensation of heavy weight on the chest), intruder hallucinations (ghost figures) and illusory movement. The likelihood of ISP is increased by lifestyle factors such as decreases in sleep quality, long naps, and of course, excess stress and alcohol consumption. It's no surprise then, that as I completed the halloweekend bender, under the stress of a relatively new city, friends and course, that the horrors of ISP managed to sneak in.

ISP episodes occur in the transition between sleep and wakefulness. During sleep, the pons and ventromedial medulla (areas of the brain stem) suppress movement of skeletal muscle with GABA and glycine (your brain’s main inhibitory signalling molecules). This stops you from acting your dreams out and destroying your aesthetically curated bedside table setup. Sleep paralysis occurs when you wake up before that muscle inhibition is over, resulting in the sensation of feeling hyper-awake, while paralysis remains.

Destabilisation of your REM-wake boundaries due to disruptions like stress, alcohol and sleep irregularity can result in the manifestation of REM dream-like images intruding into your wake state. The visual and limbic systems in the brain are still essentially dreaming while you’ve woken up under the inhibitory influence of GABA and glycine. The overactivity of the amygdala – an area of the brain responsible for emotional reactivity – explains the intense fear, and the lags in comprehending your environment due to your prefrontal regions still coming around. Disruption in the temporoparietal junction during REM-wake interference is associated with perception of eerie presences and mismatched sensory input. As a result, your brain can attribute its own bodily sensations to another being. The likely cause of hallucinations is the dysfunction and interaction of systems which normally provide you with restorative sleep and not terrifying paranormal encounters.

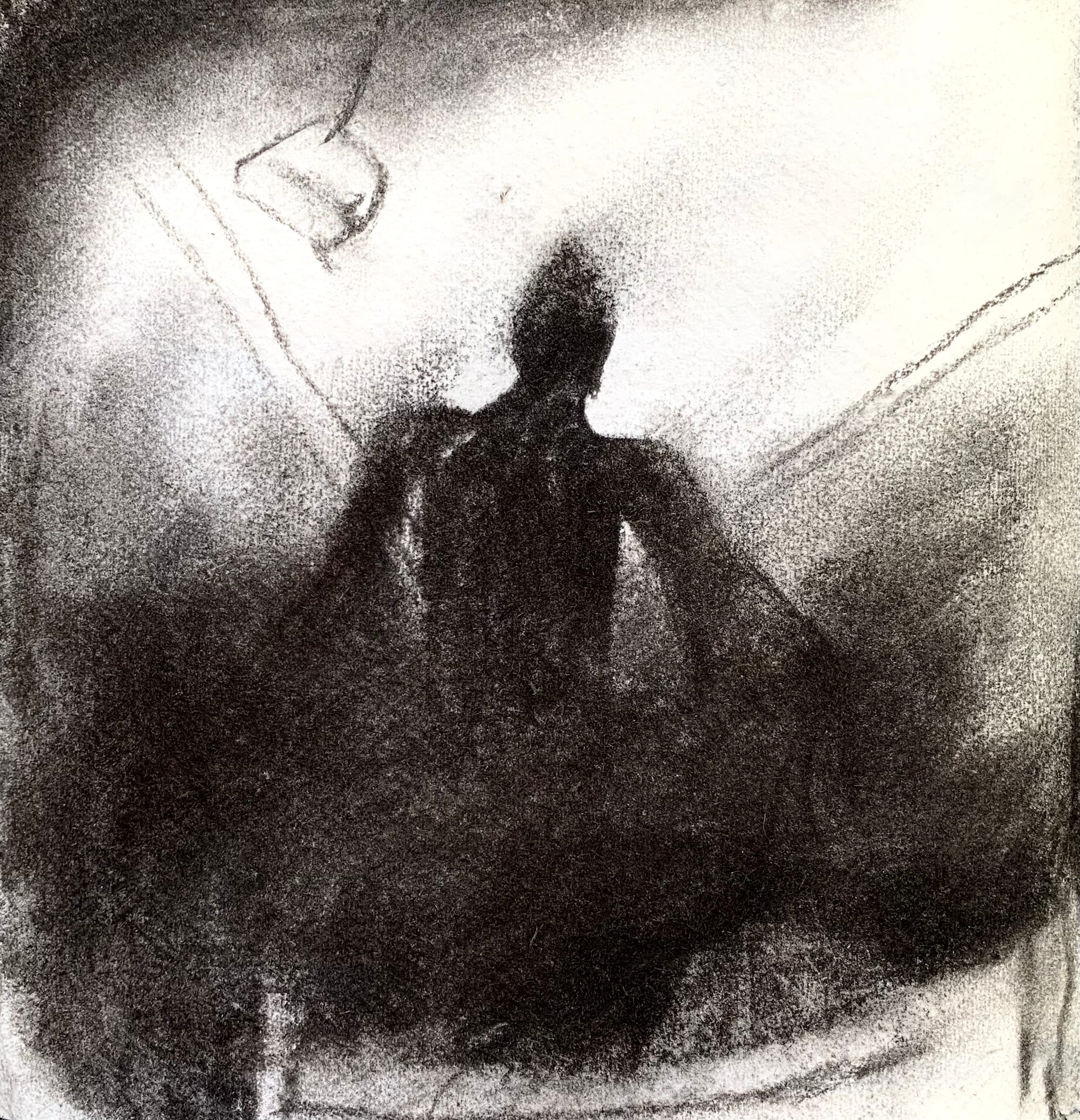

Sleep paralysis could be the explanation for a multitude of historical accounts of demons, spirits and accounts of incubus syndrome. Across multiple cultures, accounts of sleep paralysis have been interpreted as paranormal encounters: in traditional Nigerian culture, attacks from female demons at night cause paralysis; in Japanese, ISP can be attributed to vengeful spirits causing suffocation (maybe an explanation for incubus hallucinations); Canadian eskimo shamans believe ISP to be the work of spells, paralyzing the poor recipients and causing shapeless presences. Accounts of incubus syndrome, the underpinning theme of recent cult-favourite Nosferatu, is thought to originate in experiences of ISP in women, who report experiencing dark sexual encounters with demons as a component of sleep.

Fortunately for my fresher self, scientific rationalisation alleviated some of my concern. I found accepting that stress had led to a little blip in my brain’s sleep-wake systems a lot more manageable than entertaining ideations of curses, demons and ghosts. Although the brain can play horrible, cruel tricks on us, it generally does a good job at dealing with the complexity of existing day to day. Maintaining lower stress, healthier sleep and lightening up on the ciders is definitely a simpler fix than sourcing a priest happy to exorcise Badock hall.

Featured illustrations: Pheobe Veitch