By Neha Maqsood, Second Year Medicine

Neha Maqsood discusses her transformative move from Pakistan to Bristol.

I am not British, nor am I ‘British-Pakistani’. My accent, which is a mixture of Pakistani-English with a hint of American, has made it difficult for people to decipher what my heritage is. Pakistan is the country in which I was raised; my roots are buried deep in its soil and its culture and traditions are crystallized in my soul. But today, at this very moment, after spending 1.5 years in Bristol, it is safe to say that the disconnection I feel to my own country, has never been greater.

I see the porters come rushing to me, shouting loudly, ‘Baji, bag daydain!’ (Give me your bags, miss!) are they unaware of the fact that I lugged this 24kg suitcase on my own throughout Heathrow and Dubai International? Perhaps they are unaware that acts like carrying your own luggage is the norm in the UK.

Having lived in Bristol for 1.5 years has drastically altered my mindset, mentality and cultural thinking for the better (in most ways, anyway). Just as the university prospectus said I would, I have had the pleasure of encountering a diverse group of friends hailing from South Asian countries like India, Bangladesh, Philippines and Thailand, and the list goes on.

When a person gets the chance to interact with different races and cultures, it broadens their perceptions and breaks down prejudices; which was, luckily, the case for me. Due to the greater freedom regarding choice of clothing, my style of dressing was influenced by Bristol’s liberal touch; a pair of skinny jeans and a woollen jumper became my go-to look. My tone became louder, my voice stronger and used to express opinions on every international matter. Late night strolls around Clifton Village during first year, became the norm.

Bristol: Due to the similarities in our cultures, my closets Indian friend and I would have profound conversations about the patriarchal Pakistani and Indian societies’ and the difficulties such societal thinking posed to us women. These deep-seated talks would dominate out dinner-table conversations. Walking to lectures, discovering new locations, grocery shopping and cooking for myself; in some way, all these little acts provided me with an unexplainable confidence.

But I am not allowed to go there alone; and if I insist, it is only if I have a chaperone. I refuse. Whatever happened to the long walks, simply alone with my thoughts?

It allowed me to seek independence from the older version of myself. The aforementioned acts like catching the bus or walking with a friend late at night, may seem like a normality or a regular task for people in this country, but coming from a developing, semi-conservative and partially religious country, one needs to understand how different it is to do this!

Don’t get me wrong, my high school education was completed at a prestigious Grammar School in Pakistan, which was actually founded by the British when they colonised the subcontinent, so my thinking is quite liberal, and my dressing is not so conservative. However, the fact of the matter is that when one lives in a conservative country, she has to fit in with the societal and traditional norms and do as the patriarchy deems appropriate.

City of Saints, Multan, Pakistan

Karachi, Pakistan: every time the Emirates planes hits the tarmac in Karachi, Pakistan, I am instantly aware that I have arrived home. It is often an unspoken awareness; factors like the blazing sun or the fact that ‘Urdu’ and not English is the spoken language, make me feel like I have arrived home. However, the first time after returning from Bristol, the feeling of, ‘I’m home!’ did not hit me.

As I stepped into the airport, the hot winds instantly threw my hair into a frenzy and the humidity made me regret my decision to don a turtle-neck sweater (the latter protected me from the icy winds at Heathrow. I see the porters come rushing to me, shouting loudly, ‘Baji, bag daydain!’ (Give me your bags, miss!) are they unaware of the fact that I lugged this 24kg suitcase on my own throughout Heathrow and Dubai International? Perhaps they are unaware that acts like carrying your own luggage is the norm in the UK. Unsurprisingly, only the young females get asked for help by the porters, which begs the question: Is it inconceivable that a young woman can carry her own load?

As I look up, I feel the eyes of policemen, families waiting for their loved ones and strangers, on me. I feel the disapproving gaze of the religious woman donned in a ‘Burqa’ as I try to tug my sweater below my thighs which proves nearly impossible. I feel the leering gazes of Afghani men who refused to look away, making me increasingly uncomfortable. For the first time ever, I feel like a foreigner in my own country.

I miss Bristol when I am home, and I am homesick when I am in Bristol. However, it is not the friends or the academics pulling me back to Bristol, but rather the freedom.

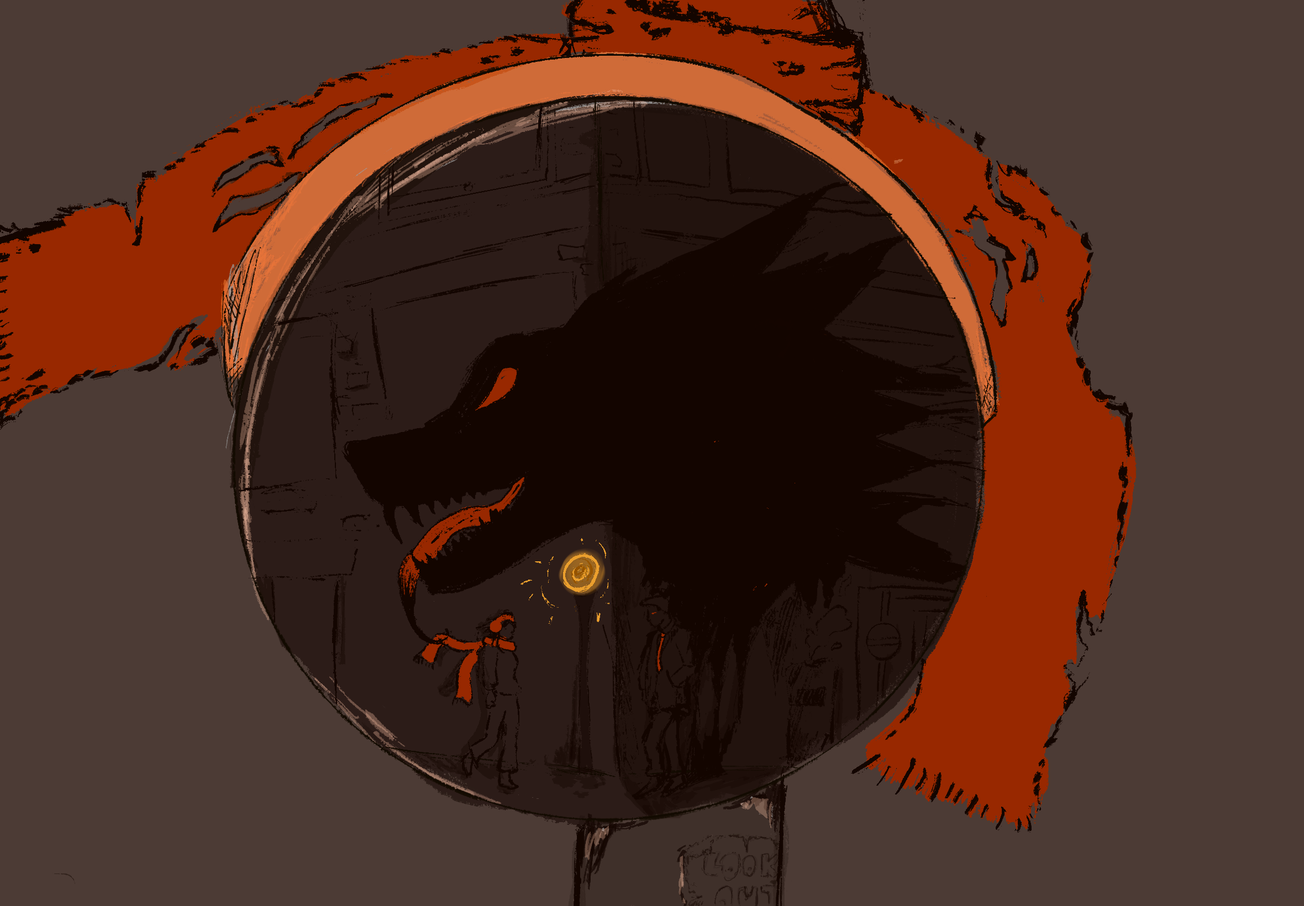

A week into returning home and everything is different. I know there is a nearby café, just like there was a Café Nero five minutes away from me back in Bristol. But I am not allowed to go there alone; and if I insist, it is only if I have a chaperone. I refuse. Whatever happened to the long walks, simply alone with my thoughts? Why is my clothing now looser, my tone more hushed? Why are my male cousins allowed to sit in restaurants or loiter the streets till dawn while I must be back in my room before dusk? I am now confined within these four walls of my room; my routine dictated by the patriarchal values of society. Four walls keeping me in. my gender, dominating patriarchy, my gender and once again, my gender.

I miss Bristol when I am home, and I am homesick when I am in Bristol. However, it is not the friends or the academics pulling me back to Bristol, but rather the freedom. I had no chains on my hands here. I was never trapped within the 4 walls, within this ‘box’ back in Bristol as I know both my mind and me are both bigger than this ‘box’.

Adaptation, for me at least, will be the key to settle in two vastly different countries which are home to polar opposite cultures and people. Although it is tough to constantly mold the mind each Christmas or Winter break when I return to Pakistan, it is a task which I have to accept. Without adapting to alternate traditions, I would probably be stagnant; I would be unable to move forward with my life. At the end of the day, the truth of the matter is that no matter how great my dislike is for chaperoned visits or long tops covering my thighs, my love for the simple notion of ‘home’ will always trump the aforementioned unbearable adaptations.

I am thankful for Bristol and grateful to its liberal culture. However, if I were ever to choose a country to spend my formative years in, Pakistan would always be my first choice.

Bristol is simply a recession for me; it is a break from the chains of my country’s rules and the Pakistani mentality. It provides much needed relief, which undeniably has given me brilliant experiences and broadened my perceptions. I am thankful for Bristol and grateful to its liberal culture. However, if I were ever to choose a country to spend my formative years in, Pakistan would always be my first choice. The very idea of the word Pakistan is synonymous with terms like ‘family, friends, love, cousins, culture’. Although my rant in the earlier paragraphs may have seemed like I was putting down my own country, despite it all, the conservative thinking and the religious culture, with some adaptation and evolving, I will consistently choose home over anything.

Featured Image: Unsplash / rawpixel

Want to write for Features? Get in touch!