My Bristol is a new features column exploring the diversity of experience of the 22,000 students at our University. Exploring faith, race, gender, health and other concerns of our day, it will prove that a community like ours is a prism for wider society, and that to tell our stories is to tell a small part of the world’s story.

For the first article Ellie Sherrard and Richard Assheton met Chloe Tingle, whose social enterprise No More Taboo was last month named Enterprise Nation's Female Start-Up of the Year.

A ‘sheet of paper’ is little recognition for the life-changing work Chloe Tingle has already done. In June last year she graduated from Bristol. In March this year she launched No More Taboo. By October she was Female Start-Up of the Year.

‘It popped up in an email, and I was like, ‘Ah well, I’ll go for that,’’' she says modestly, her laughter keeping us awake in the stuffy Queen’s Building café.

Later she tells us how nervous the other two finalists were. They weren’t used to pitching. Chloe was; her Engineering Design degree often required class presentations.

But it wasn’t her presentation skills that won it for her. It was clearly her conviction in her cause, her humility and the strength of her idea.

Untying and retying her hair into a bun, she gives us a summary:

‘No More Taboo sells sustainable menstrual products, and uses the profits from those sales to fund our projects in developing countries and the UK based around menstrual hygiene.’

In Bolivia, where Chloe was inspired to start the project, some believe that eating onions whilst menstruating gives you cancer.

In Uganda, where she volunteered last year, some believe that crossing a peanut field whilst menstruating kills all the crops.

‘In the UK’, Chloe says, ‘[menstruation] is only really talked about in whispers, in kind of, close family circles.’

No More Taboo aims to break down these myths and taboos, to get people talking about menstruation – to make what is natural normal.

In an average woman’s life she will spend between £1,400 and £3,500 on over 11,000 sanitary products.

The result is 150kg of waste, which will take over 500 years to decompose.

Chloe grew up in the West Yorkshire countryside – in Holmfirth, Last of the Summer Wine country, a small town of grey stone amid dewy green fields. As a child she was obsessed with recycling.

‘A lot of this interest comes from my mum being very green,’ she beams. ‘She always wanted me to be an inventor!’

At Bristol things crystallised. Interested in water and sanitation, Chloe took a unit in innovation, entrepreneurship and enterprise.

‘I absolutely loved that unit. It was really really – just absolutely ticked all the boxes,’ she says.

Last year, freshly graduated, Chloe knocked on the Dean of Engineering’s door and asked if he might help her fund a volunteering trip to Bolivia. He gave her £1,500.

‘If I hadn’t been a bit ballsy about it I probably wouldn’t have been able to afford to do the whole time that I did,’ she says.

‘I wouldn’t have done the project that I did.’ Chloe wouldn't be sitting where she is now, in a bright pink NO MORE TABOO t-shirt.

‘I think, just go for it. Don’t worry too much about where you think it’s gonna go. And always ask. Do something you enjoy and don’t worry too much about the future.’

Chloe arrived in Bolivia the right person at the right time. Fundación Sodis, the organisation she went to work for, had the perfect project for a female engineer.

She was sent to Cochabamba, Bolivia’s fourth city, ‘The City of Eternal Spring’, to work on a pilot menstrual hygiene project with a handful of other volunteers.

There, a focus group of teenage girls opened her eyes. 90 per cent had started their periods. They all aspired to use tampons – those that couldn’t, used rags – but all of them worried about the impact on the environment.

‘I had literally never thought about how women in developing countries manage their periods at all. It had just never crossed my mind.’

Chloe had used a menstrual cup for years, but the girls inspired her. She found someone producing them there, sold around 30 to volunteers and gave some to the girls.

Clearly there was a market for healthy, affordable and sustainable alternatives to tampons. Repeatedly Chloe wonders out loud what the girls now think of them.

She decided to set up No More Taboo as a social enterprise: it does not make a profit – any money earned goes to funding the educational projects she is involved with – but unlike a charity it aims to grow without external funding.

‘I want all the profits to be spent on the charitable side,’ she tells us, a fact which causes much bemusement amongst her Bristol friends on graduate schemes.

So why should people buy her products and not tampons? How can she persuade people to change their habits?

‘Having done more research on it I know that there are absolutely no regulations on the disposable industry,’ she tells us.

Billions of women around the world are using sanitary products that could contain harmful chemicals.

‘When I think about what’s actually in tampons I really don’t want to put that anywhere near my body,’ Chloe says.

We think about Toxic Shock Syndrome and the decisions of supermarkets and pharmacies to label Tampax and other brands ‘feminine care’ products.

Chloe claims that by its fifth birthday No More Taboo will have saved 743 tonnes of waste because of women switching from tampons.

A menstrual cup can be used for ten years before being thrown away. Depending on the model it costs either £11.00 or £19.99 on Chloe’s website. She thinks she might have also saved women £16 million in that five years.

Apparently there are people on Facebook talking about ‘the dawn of the menstrual revolution’. Chloe giggles. The issue is ‘trickling through in the press’.

So why aren’t these products flying off the shelves?

‘There’s a wall and you need to break it down quite slowly,’ she says. ‘I get a lot of "Eww! What is that? No way would that go up!"’

In the UK Chloe hopes to change curricula so that children and teenagers, both girls and boys, are better informed about menstruation and know that there are alternatives to disposables.

In developing countries she wants to do the same by working with local educators. In March next year she heads to Nepal.

‘The difficulty is that some of these taboos are so inherent that the people teaching are passing some of them on,’ she explains. ‘You can provide the facts but you can’t provide the cultural understanding.’

Chloe is excited about the future, but no one can say what it holds. For now, she is concentrating on keeping No More Taboo going, working three days a week to pay her Montpelier bills. ‘There are a lot of forward-thinking people here in Bristol.’

But for all of us it’s a challenge to start talking openly about menstruation.

‘I went out with a friend for lunch the other day,’ she says, smiling. ‘He’d told his mum what I’d been doing. She literally spat her coffee across the room and shouted, "She does WHAT?"'

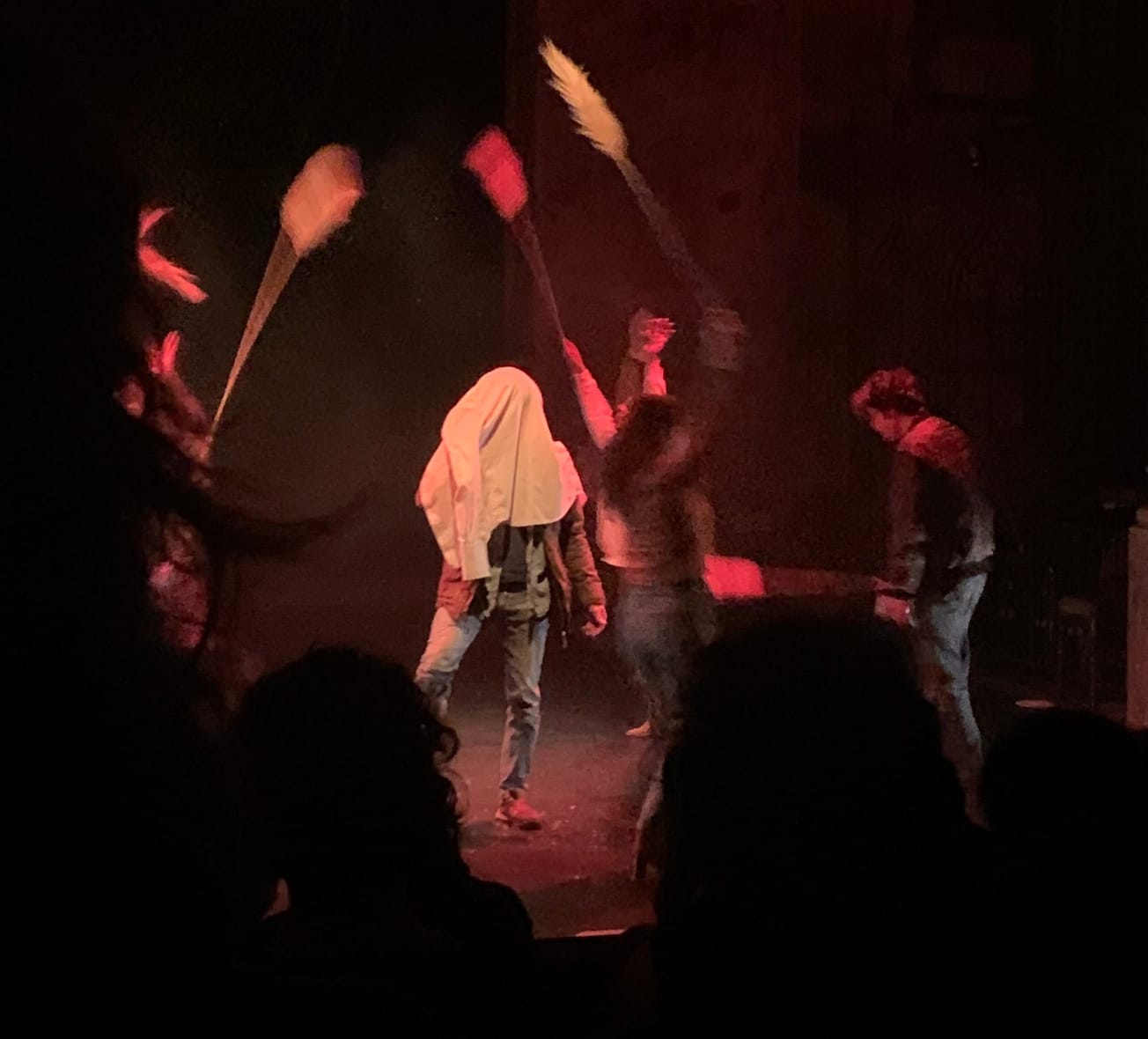

Reusable Pad Party, Bolivia

Do you think we should be using alternatives to tampons? Let us know in the comments below or tweet us @EpigramFeatures.